Value of Human Labour

Lessons from Lockdown

Foreword

Covid-19 has profoundly changed the way we work. Whether that's the extinction of the daily commute, being furloughed by your employer, or wearing personal protective equipment as a key worker, the pandemic has effected every single profession on the planet.

Perhaps unexpectedly, the virus has created positive changes in working cultures and habits that many workers may hope to last in a post-pandemic world. Indeed, managers can no longer rely on arguments against working from home, which could innovate the traditional 9-5 structure as employees come to be appreciated based on the targets they meet, rather than the time they spend behind a desk.

In many nations, the novel coronavirus has also sparked an important conversation about the type of workers society values. Whilst the majority of us were bound by stay-at-home orders, traditionally low-paid professions, such as cleaners, nurses and supermarket operators, resumed their roles as essential workers in the fight against the virus. Now, they feature as the centrepiece of an outpouring of public support for the frontline.

However, whilst more workplaces are encouraged to return to face-to-face operation with the easing of lockdown, it is yet to be determined which new working norms will stick. The volatility of the labour market has disproportionality effected vulnerable communities, such as Black, Asian and working class groups, who make up a high proportion of frontline workers. Additionally, women also face a greater risk of redundancy than their male counterparts due to the large female workforce in sectors such as retail and hospitality. They have also been hit the hardest by childcare responsibilities, as parents are forced to tackle homeschooling in the absence of external carers. Moreover, 18-24 year olds, whilst largely shielded from the worst effects of the virus itself, are predicted to be hit hardest by a shrinking international job market.

This publication features a collection of articles from academics across The University of Manchester, fleshing out the key issues facing human labour in a post-pandemic world. Each article makes a series of recommendations as to how policymakers could seize this chance to protect workers now, and minimise the social and economic consequences in the future.

What COVID-19 tells us about the value of human labour

Abbie Winton and Professor Debra Howcroft

In the wake of the coronavirus outbreak, a radical reassessment of what is considered ‘key work’ has taken place. For many key workers, however, this status is not reflected in their salary, employment rights, or social perception. Here, Abbie Winton and Professor Debra Howcroft, from the Work and Equalities Institute, discuss the disproportionate risk/reward equation key workers – particularly women – face, how the COVID-19 crisis will impact their future, and what policymakers can do to address inequalities at work.

On 19 March, the UK government published a list of ‘key workers’ considered to be critical to the provision of services during the COVID-19 crisis. These workers amount to 7.1 million adults across the UK, the majority of whom are female. Many ‘key workers’ receive the National Living Wage, the minimum wage set by the government for over 25’s. These workers are vital for society to function, yet the degradation of the employment relationship illustrates how the value of labour is not dependent on an impartial measure of supply and demand but is constructed by the social context within which it is embedded. In light of the current crisis, a radical re-think of how labour is valued – both socially and financially – is needed, leading to policies which ensure that key workers are paid and protected in a way that reflects their critical contribution to society.

Gendering of ‘key workers’

Of the designated ‘key workers’ in the UK, 60% are women (compared to 43% of workers outside of these industries). As a consequence, 77% of workers in occupations identified as being at ‘high-risk’ of contracting COVID-19 are also women, underlining their role in frontline work.

The predominance of women as ‘key workers’ is a result of the historical normalisation of ‘women’s work’, and persistent structural inequalities within waged and unwaged work. Numerous occupations remain largely feminised and are often valued less than occupations associated with ‘men’s work’, despite requirements for equivalent skill levels (eg social care and construction work require comparable NVQ levels).

Feminist theory informs us that how society perceives, and constructs skills is a pervasive determinant of value as opposed to the actual skill required to do the job. Feminised roles have long been deemed ‘unskilled’ or ‘low skilled’ as they are seen as an extension of unwaged work in the domestic sphere (eg health, social and child carers, cooks, cleaners). Therefore, although many of these feminised ‘key roles’ provide a critical service, they continue to be undervalued.

The mismatch of skill and value

While some key workers are employed in ‘skilled’ professional roles, many are categorised ‘unskilled’ or ‘low skilled’ according to Standard Occupational Classifications (eg food production, sales and delivery, social and other healthcare roles). While the social value of certain roles fluctuates depending on the needs of society at any given time, the financial value of work remains bounded by the social perception of the skills which the role demands. This bias which shapes evaluations of skills is likely to deepen inequalities and the way in which work is valued.

What is the future for ‘key roles’?

While some suggest that COVID-19 generates uncertainty for future investment in automation, a survey of employers shows they are accelerating plans to automate roles while workers stay at home. Future uncertainty is of concern for women as they are likely to be disproportionately impacted by processes of automation given their concentration in particularly vulnerable roles, such as sales and cashier roles.

Considering the example of food retail, the demands of the crisis has demonstrated the value of human labour, as well as the importance of skills which are commonly overlooked and undervalued. For example, activities which require non-cognitive skills (shelf-stacking, picking and packing), or require an element of ‘human-touch’ (helping elderly and vulnerable members of the public, monitoring social distancing, intervening in practices of bulk buying) remain difficult to automate.

In the UK, to cope with increases in demand, 45,000 temporary jobs have been created in food retailing and existing roles have intensified, both in terms of consumer expectations and working-time (exemplifying many ‘extreme work’ characteristics, such as extended working hours, increase in demands for multi-tasking, and the regulation of emotion of both colleagues and customers). In the US, 100,000 new jobs have been added in Amazon’s fulfilment and distribution network, even though many of its warehouses rely largely on robotics systems. Therefore, while employing people often remains cheaper than investing in new technology, certainly in the short-term, a lesson we have learnt is that technology alone cannot save us in a crisis.

What policymakers can do

Given the increasing prevalence of precarious working conditions (such as zero hour contracts, underemployment, and unstable hours) full employment rights and adequate social protection should be extended to all key workers. Gendered assumptions around skills in the workplace require an overhaul, so that traditionally feminised occupations receive appropriate recognition and recompense.

In parallel to this, a re-assessment of social value is required so that key workers operating on the front-line, many of whom are risking their health, are fairly rewarded by pay which reflects this. In times of crisis we see how those who are critical to the functioning of society are largely undervalued and often low-paid. The public response to ‘clap for carers’ symbolises an appreciation of social value from grassroots level, which will hopefully influence policymakers and result in a levelling up that is long overdue.

The Standard Occupational Classification needs to be re-evaluated in line with technological advances shaping both the supply and demand of skills, with a focus on the way in which skills which defy automation are valued. Investment in technological change is to be welcomed, but on condition that potential productivity gains are redistributed with a view to creating a more equal society.

Originally published 7 April 2020

#HereToDeliver: Valuing food delivery workers in the future

Cristina Inversi, Aude Cefaliello and Tony Dundon

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the fore a new cadre of valued workers. And it’s not the corporate CEO or senior business leader but the delivery workers that are helping cafes and restaurants stay open (in some form) during lockdown. Cristina Inversi, Aude Cefaliello and Tony Dundon of the Work and Equalities Institute (WEI) report on health and safety risks and legal loopholes of gig-economy work.

It may come as a surprise that the gig-economy has been at the forefront of the COVID-19 responses. We all know how brave health and care workers are, along with other front-line workers in supermarkets, in protecting people and keeping society functioning. So too are many workers who have been undervalued and have had to rely on bogus self-employment. Delivery drivers (and riders) of fast food and other services have had their work regulated through technology and smart phone apps, with adverse health and the safety consequences:

· 25,000 self-employed couriers work for Deliveroo in the UK, as of 2019.

· 42% of gig-economy couriers and taxi drivers report vehicle damage because of a collision.

· 63% say they had not been provided with safety training on managing risks on the road.

· Around half of gig-workers have lost their jobs and the rest have had their income cut by around two-thirds because of COVID-19.

The legal loophole enjoyed by platforms

Many gig-platforms are doing very little, if anything, to protect their workers during COVID-19. Some platforms are well-known for benefiting from a legal loophole. Because delivery drivers/riders are considered independent contractors, allegedly managing their own small business, they are outside of the protective wing of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974. In practice, gig-workers have to accept self-employment status, which has significant effects on their health with low pay. Being in a situation of precarity increases stress, anxiety, and tiredness. Many key front line workers encounter gender discrimination and other forms of exploitation, such as zero-hours work. As a result, the risks of doing business – including health and wellbeing risks – are passed from the platform to the individual worker, with a lack of insurance coverage, little if any legal protection and no compensation in cases of sickness or injury.

Layering of risks

Workers in the gig-economy have been exposed to a growth in health risks: road accidents, fatigue, stress, attacks, job insecurity and poor mental health while working through the COVID-19 pandemic. New risks have been created from new forms of work management, AI and online devices. The novelty of digital management control represents a new occupational safety and health (OSH) challenge for lone workers who have no standard or permanent place of work: the platform organises all tasks with extensive control through data gathering of workers’ movements. The information is only used by companies for their benefit and never to improve working conditions or health and safety protections for employees.

Our research shows that these workers have unique insights and skills to enhance gig-economy business models, but their suggestions fall on deaf (employers’) ears. For example, workers could have the option to alert the platform when they have an accident, so the first aid or emergency services can be contacted if necessary. Couriers and drivers can transmit information to share knowledge about known incident areas, hazards risks on the road, extreme weather conditions, etc. However, platforms rely on one-way dialogue and measure only time of delivery. They do not collate health risks that can support a better public goal.

The lack of platform accountability and action on OSH issues shows the limits of the self-regulated approach, which underlines the urgent need for better policy and regulation of known risks.

Opportunities for a fairer future?

The 2020 pandemic and the subsequent COVID-19 crisis showed that food carriers who work for some of these platforms (eg Deliveroo and UberEat) are considered ‘essential frontline workers’. They have been crucial for the survival of small business restaurants and provide a necessary service to those who have had to self-isolate and cocoon during difficult times. Even in the stricter lockdown situations, these employees never stopped working, exposing themselves to considerable hazards and personal health risks, with very little (if any) individual personal protective equipment (PPE) provided by companies. Public concerns have been raised in terms of health and safety, responsibility and insurance protections for this precarious segment of the labour market. Beyond the pandemic situation, the overall adequacy of the OSH legal framework for this growing population is unacceptable based on equity and fairness.

From our own research data on health and safety risks along with analysis of existing legislative loopholes on bogus self-employment, new and more equitable regulatory instruments are desperately needed for these frontline workers. For example, employee contract status needs clarity and specific rights such as the living wage, working hours and health and safety protections, including personal protective equipment (PPE), ought to be provided by the employing platform as a basic condition of service. The role of the State, which can include local authorities in city regions, can be essential for monitoring unregulated labour platforms and ensure at a local level health and safety rights are adhered to in the spaces where such self-employed workers congregate and work. Indeed, the safety of one group who are defined as self-employed because of a loophole, ought not to have inferior rights compared to other citizens and workers.

As it stands now, it is evident that a purely voluntary approach emphasising self-regulation of digital labour platforms is ineffective. There are now opportunities to design more equitable regulatory instruments inclusive of a wider spectrum of stakeholders, with a focus on minimising health and safety risks while also monitoring productivity and, above all, a system to value those in society who have been undervalued. At national level such stakeholders can include trade unions, the Health and Safety Executive, Employment Standards Inspectorate, along with employer associations. At regional levels, policy roles can exist for local authorities, chambers of commerce, or civic society groups concerned with city spaces and regional planning, as well as education providers who may offer bespoke training in areas of technological skills, road safety and other learning interventions to mitigate risks that have been that pushed onto these individual workers.

Originally published 25 June 2020

The voluntary and community sector and COVID-19: Going to war without ammunition?

Sophie Yarker, Kirsty Bagnall, Tine Buffel, Patty Doran, Camilla Lewis and Christopher Phillipson

COVID-19 has forced us all to rethink how to maintain social connections in the neighbourhoods where we live and work. For the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector (VCSE), this has meant a rapid rethink in how to provide services whilst observing social distancing guidelines. Here, Sophie Yarker and Kirsty Bagnall, along with Tine Buffel, Patty Doran, Camilla Lewis, and Chris Phillipson from the Manchester Urban Ageing Research Group (MUARG), discuss the challenges the sector is facing and suggest an alternative approach to providing support.

Whilst the demand on organisations continues to increase, their ability to respond to COVID-19 has been substantially reduced due to cuts in public sector funding, which has reduced or disappeared over the years. Research suggests that smaller charities (with annual incomes of between £100,000 and £500,000) lost nearly half of their income from local government in the five years following the 2008 financial crash. On top of cuts to their own funding, the social infrastructure that supports the third sector has also been under attack. Some examples include: 12,000 public spaces sold in the past decade by UK Councils ; the closure of libraries (800 since 2010); the privatisation of leisure centres; and the decline of local shopping centres in many areas. All of of these developments have led to the decline of spaces vital for social participation. The present crisis has further revealed inequalities in the extent to which neighbourhoods are able to respond to the challenges arising from COVID-19. The presence of mutual aid networks, for example, has emerged overwhelmingly in places with strong neighbourhood networks and a thriving social economy. Such communities are much better equipped to develop responses, as compared to those with less capacity to mobilise resources and reach out to vulnerable groups. The COVID-19 crisis is thus amplifying existing inequalities between poorer and richer neighbourhoods.

Reducing social isolation in a time of social distancing

VCSE organisations are a vital part of the social infrastructure of neighbourhoods providing places of support, advice and social contact. As such, the sector is particularly important for older people, who are often more reliant on their immediate locality for both social participation and support. VCSE organisations have increasingly been tasked with mitigating social isolation and loneliness for older people by providing opportunities for social interaction with others. The question, then, is how can initiatives aimed at reducing social isolation continue to be delivered in the context of social distancing?

Our research into tackling social isolation and building age-friendly communities in Greater Manchester has identified several innovative ways community organisations are responding to the challenge. The majority of Age UK branches, for example, have moved their services online or by telephone, with branches trialling new approaches to addressing social isolation. Infrastructure organisations, such as local community and voluntary services and organisations, whose operations are based around food, have moved towards direct services, co-ordinating and providing food parcels, and managing volunteers. And ethnic minority organisations, such as Europia, have developed informative videos for a number of communities for whom English is not their first language, and would therefore miss out on important information about COVID-19. In many cases, this extends the vital work organisations have already been doing to reach the most marginalised groups in our communities.

Figure 1. 84.3% of people provided support via shopping to non-household members

Unequal impact

Not only do the uneven impacts of austerity challenge the capacity of communities to respond to the immediate crisis of providing essentials such as food, medicines, support and advice, there is a significant risk that these inequalities become even further entrenched as the community and voluntary sector starts to re-orientate itself towards a future of working with social distancing.

One of the most pressing issues concerns the loss of funding. Back in March, the #EveryDayCounts campaign, led by NCVO, calculated that the charity sector could miss out on a minimum of £4.3bn of income between April and June 2020. At the beginning of April, the government announced a £750 million package to support the work of charities during the current crisis. This support, whilst welcome, is unlikely to be accessible to large parts of the sector. Many smaller organisations are likely to miss out, despite the injection of funding.

Over 80% have an income below £100,000; those with an income over £1 million are fewer but account for more than four-fifths of the sector’s income. There is a substantial risk that emergency COVID-19 funding will disproportionately go to larger voluntary organisations, with concerns those with the most resources will apply first and take most of the money allocated. The latest State of the Sector survey carried out in 2017, showed that 46% of VCSE organisations in Greater Manchester have less than three months of running costs in reserves, a major concern given the depth of the crisis facing communities.

An alternative approach

We have already seen many within the VCSE sector using emergency funding and reserves to rise to the challenge of adapting existing projects in response to the challenges posed by COVID-19, from coffee mornings moving online, telephone-supported digital inclusion courses, and craft clubs introducing postal delivery of materials, to allotment groups making adaptations around social distancing and hygiene measures allowing them to return.

However, there is a further, more complicated challenge in creating means of new social connection, rather than adapting what already exists. Reaching and supporting those who do not already have connections within their local communities is made all the more difficult by the pandemic. Organisations will undoubtedly require financial support but this is unlikely to be sufficient to meet the challenges facing voluntary groups – especially those working in poorer communities. Based on findings from our research in Greater Manchester, we argue an alternative approach is required, one which allows organisations to test new ways of working, invest in skills and leadership, and share learning about new ideas.

Offering smaller pots of money for investment (up to £2000) can encourage organisations to take more ‘risks’ and to be more innovative with their ideas, knowing that they do not have to ‘get it right’ first time. The learning from projects that have not gone as planned can be just as useful if shared through networking events and co-operatives. Examples from the Ambition for Ageing programme include a Crafting Co-operative in Bury set up to bring together local groups interested in craft work, and in Bolton networking events were set up in each ward to bring together those who had received similar funding to share their experiences and future plans with each other.This could be supported by a delivery and management approach that prioritises relationships and dialiogue-building by, for example, giving contractors a set of quality standards from which to design their own specific goals and targets which reflect the needs of the communities they work with.

This more flexible approach will be essential for the community and voluntary sector to respond effectively to the new context of social distancing. This requires a closer dialogue between organisations and funders to allow organisations the time and support to do this work. This aspect will be crucial for equalities organisations who themselves are the least resourced yet working with those who are often affected the most by COVID-19. This might mean adjusting procurement and commissioning to reflect a more flexible test and learn approach, and methods of monitoring and evaluation may also need to be revised to reflect different goals and outcomes.

However, any recovery or indeed reinvention of the sector will be shaped and constrained by place-based inequalities. For older people living in low income communities, who are already more at risk of social isolation, a declining community and voluntary sector will mean less support available on their doorstep and less opportunities for social and civil participation. Alarming statistics from the ONS reveal that those living in the poorest parts of England and Wales are twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than those living in more affluent areas. Far from being a ‘great equaliser’ this highlights the seriousness of the crisis facing our already most besieged communities.

Originally published 16 June 2020

Recognising the value and significance of cleaning work in a context of crisis

Professor Miguel Martinez Lucio and Dr Jo McBride

Professor Miguel Martínez Lucio of the Work and Equalities Institute and the Alliance Manchester Business School and Dr Jo McBride of Durham University discuss the question of how we have failed to value the work and importance of those in the area of cleaning and hygiene-related employment more generally. The need now is to consider how such workers are engaged with and supported through a greater framework, with respect and dignity being paramount. This is essential if we are to overcome the challenges of ongoing crises such as that of the current pandemic.

Even before the introduction of social distancing at workplaces, many cleaning workers found they were working more in isolation (due to job cuts and less supervision). We interviewed cleaners working across four different public sector organisations to learn about their experiences in the workplace. Alongside working more in isolation, many cleaners are being left to decide what they feel is a work priority, indicating that they are taking on more of a decision-making role in the workplace. This sense of increasing discretion could be perceived, albeit superficially, as a further complexity of the work. This undermines the use of the term ‘unskilled’. Others began to draw out a growing sense of awareness of the negative context of the environment and the way it impacts on their work and decision-making.

The context of safety and violence in many aspects of cleaning

Due to the growing isolation of their work, many of the cleaners we interviewed felt they were also at greater risk in terms of danger, fear, and violent threats. Cleaners who worked alone explained how they had experienced more direct forms of threats, particularly when working in public spaces. Levels of physical abuse were significant. Many of these workers perceived recent cuts to their operations as a contributory reason for an increase in negativity by the public and were having to respond to this in various ways. One domestic refuse collector told us: “Oh, you get abuse all the time, like. I’ve had stuff thrown at me, bags and everything. They come out and swear and shout at you.”

Austerity and cutbacks

Street cleaners especially have needed greater discretion in their job, not only in threatening or violent situations, but also when facing hazards to their health in the work they undertake, such as when handling discarded, dirty needles on the streets. Cleaners have to also help each other develop their knowledge of challenging areas of work and how to respond without the necessary materials. Their roles are expanding to the point where they include managerial dimensions in terms of decision-making and using greater levels of discretion in terms of thinking through the consequences of actions. It is increasingly clear for the street cleaner to be given more responsibility of supervising another worker yet for this not to be valued remuneratively or by management. These are administrative features of their work which do not actually get recognised.

Stigma and the feeling of being valued

One of the challenges facing cleaners in recent years is the stigma attached to the job, as they are seen as unskilled and low paid. These concepts reinforce a sense of worthlessness – and that the job being done is ‘unimportant’.

In terms of stigma, and its related factors of dirty work, unpleasant work and risk, internal cleaners in our study thus received negative social perceptions of their work but also of the whole purpose of it. It is not just that the person doing the job is undervalued, but that the purpose of the job and its significance is simply not fully understood. This has a massive impact in terms of the way the economy is misunderstood and the way certain core activities that are important to sustain it are undermined. In stigmatising cleaners, the whole question of hygiene and health is undermined and thus is underinvested.

This lack of appreciation and even of the recognition of new challenges of these jobs also extended to other workers in the study. These were in relation to external cleaners, some of whom demonstrated that, despite verbal abuse and a lack of respect from some members of the public, they still had a sense of feeling dignified despite others’ negative perception of their work. Stigmatising workers and seeing it as peripheral work means that the core purpose and value of that sector is undermined. This has been happening for some time and has had a major knock-on effect on the way recruitment, development and quality within the economy is undermined within its very foundations.

Yet the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced a ‘Clap for Carers’ campaign of public appreciation for workers, involving some in our study. This demonstrates a mutual social perception of the value of much of this work and there is already a re-evaluation of such work in the public discourse.

Rethinking the way we envisage work and employment

First, the value of work has to be economically and symbolically supported in a more effective manner. The way we see the economy in skewed terms and the way we envisage support workers such as cleaners has curious knock-on effects. When there is a moment of crisis and work such as cleaning is deemed suddenly to be essential, we find that these subsectors are literally unable to respond to the challenge at hand due to their demoralised state or limited support in material terms.

Second, the need to recruit, retrain, upskill and retain such workers must be pushed into the centre of the political discussion. The lack of resourcing and the aggressive, and dysfunctional, management cultures that cleaners face prevents workers from pursuing a balanced and more effective approach to their work. This has led to immense fragmentation brought on by ongoing subcontracting and performance management which is not concerned with long-term development.

Third, the very way we think of ‘unskilled’ work needs to be challenged. Even key employer organisations within the cleaning sector have argued for decades that there is a need to not just value but professionalise the work and to remove the stigma of it being unskilled. The importance of health and hygiene is an important feature of the welfare interventions of the state. The need to recast our personal and political mindsets to include the voice and concerns of bodies of workers such as cleaning workers will be a challenge for future policymakers. It is also a cultural challenge in a society where the construction and maintenance of our infrastructure has played a secondary role compared to its commercialisation.

Millions of these frontline staff, now viewed as key workers, have been keeping the country running while facing risks to their own and their families’ health. The fact that they are ‘keeping the country running’ again undermines the persistent use of the term ‘unskilled’ with regards to this work. Indeed, this work is currently being recognised and valued across our communities in a way that has not been the case for some time. We therefore need to ensure that this continues to be recognised as valuable and meaningful work.

Originally published 10 June 2020

Building back a gender balanced better – devolution, growth and equalities

Francesca Gains

As the initial period of lockdown is slowly relaxed, the policy agenda in all parts of the UK is turning to examine recovery from the economic devastation caused by the pandemic. Policymakers in our major city regions are considering how to start up and stimulate economic activity where safe to do so; help firms and employers transition to new ways of working; and deal with the inevitable growth in unemployment that will flow from recession. Here, Francesca Gains, Professor of Public Policy, discusses the need to consider gender equality when making decisions on how to build back better.

As well as these urgent economic agendas, there is also a desire to learn from the disruption of the pandemic – to think about how to ‘build back better’. To capitalise on the social and environmental benefits that lockdown revealed: strong community and neighbourly support, less traffic and pollution, less time commuting and the potential for more time for parents to share responsibility for childcare.

Fairness and equalities

The lockdown also highlighted the following issues around fairness and equalities, moving these agendas to the top of political and public awareness and debate:

· The higher risks of being affected by the serious symptoms of COVID-19 faced by men and Black and minority ethnic (BAME) communities;

· The concern for (predominantly) women and children living with domestic violence;

· The higher risks of exposure to infection faced by key workers in certain occupations, such as low paid and mainly female care workers;

· The imbalanced unpaid care done within households by fathers and mothers;

· That women are more likely to be in a job that can be done from home with consequent risks to their productivity due to increased childcare and homework duties;

· The greater risks of redundancy following furlough in sectors like retail and hospitality which have a largely female workforce.

This awareness provides a rare opportunity to get equalities policymaking on the agenda. Too often equalities is side-lined unless an economic case can be made. The current circumstances provide this strong economic incentive to build back better especially in devolved areas. Combined authorities headed by a mayor have a vital role in stimulating and coordinating economic growth through their local industrial strategies, skills investment and employment support as well as through enabling integrated public transport. Mayors can be a vital voice for the city regions, working with local authorities, anchor institutions and stakeholders helping to coordinate, target and stimulate growth. But a focus on equalities data on employment will be important in understanding how to target policy to get productivity gains.

Gender and the loss of productivity in the labour market

On Gender, produced for the Greater Manchester Combined Authority Women’s Voices Task Group in 2019, illustrates how the labour market is occupationally segregated, with women being hugely over-represented in low-paid, insecure caring and administrative sectors, leisure, and retail; and men over represented in the manufacturing, construction, engineering, technical and managerial sectors. This picture is replicated in all combined authorities.

Figure 2. The occupational disparities within the female labour market across Combined Authorities are stark.

When the gender differences in labour market participation are examined in Greater Manchester and elsewhere it is clear how women get squeezed out of full-time employment during the years of childrearing and childcare. Analysis shows that the risk of economic inactivity is an intersectional one where BAME women face an even higher likelihood of part-time working or unemployment. A lack of affordable childcare and problems with transport are seen as vital in helping women balance work and care.

The evidence in On Gender shows how the gender differences in employment, occupation and labour market participation are exacerbated during child-bearing years and feed through into gender pay gaps; and greater income insecurity in older age for women with potential consequences for wellbeing and the need for social care.

Having a gendered lens to policymaking is essential to understand how these inequalities build over the lifecycle and how to tackle these issues. For example:

· To address gendered educational choices and build gender targets into skills strategies to support construction and digital skills pathways to encourage girls and to enter occupational sectors where they are underrepresented;

· To work with employers in sectors where future innovation and growth is expected, such as the IT sector, to tackle working practices and expectations which make progression at work difficult to combine with family life;

· To promote the adoption of the voluntary living wage for low-paid workers such as those in the care sector;

· To support the development of vital childcare and transport infrastructure to help skilled female workers manage work and care.

Ensuring building back better involves building back fairer

As the agenda to ‘build back better’ develops, understanding the data on gender and inequalities in the new devolved mayoral authorities will be even more vital on economic grounds to avoid further entrenching occupational segregation. Without deliberate action to ameliorate job losses in sectors where women predominate, realise productivity gains and unlock talent by keeping women in the workforce the impact of the pandemic risks exacerbating gender inequalities.

On social and fairness grounds, Greater Manchester with its health and social care devolution responsibilities will need to work with Government, local authorities and providers to address the problem of social care funding. The vital work provided by low paid and precarious social care workers should be valued. Addressing precarious work is not just important for fairness, but also will support the foundational economy, ensuring the underpinning exchange of goods and services within very local areas.

And the role of combined authorities in supporting (when safe to do so) better public transport, walking and cycling will help achieve some of the environmental potential lockdown revealed. Supporting changing working patterns with less commuting and more working from home can be harnessed to support a balance of work and care in households helping fathers to be more involved in child care.

Now more than ever combined authorities are absolutely critical in tackling some of these pressing, cross-cutting agendas on economic, social and fairness grounds. With the budgets and decisions devolved to combined authorities the equalities agenda is key to helping with recovery.

Originally published 11 June 2020

Bogus self-employment and COVID-19: An added layer of insecurity

Martí López-Andreu

The outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis has raised concerns about its impact on precarious and vulnerable workers when most of them have been at the front line during the crisis and their work has been revealed as essential. Dr Marti Lopez-Andreu, from the Work and Equalities Institute, investigates some of these key workers in areas such as logistics and transport, among others. The current COVD-19 situation adds a further layer to these workers’ vulnerabilities and brings into the debate specific needs in terms of income support and health and safety that have not been addressed by either employers or government policies. Here, he explains what ‘bogus self-employment’ is and examines how COVID-19 is affecting these workers.

‘Bogus’ self-employment refers to subordinate employment disguised as autonomous work. Some groups that have gained attention recently include those working in jobs related to the gig-economy such as couriers and private car drivers. Other more traditional groups include those working in IT, construction and railway maintenance, among others. This is also the situation of workers in the health and care sectors; for example, domiciliary carers and foster care workers. Research has identified that their working conditions are increasingly characterised by low income and precarious working conditions.

Although these workers are formally independent workers, their capacity to maintain work over time and ensure they have access to enough work is dependent on their ability to sustain their links, contact and reputation with specific physical or virtual contacts. This includes key individuals in organisations that manage outsourced tasks, agencies that manage specific labour markets (eg in construction or railway maintenance) and, most recently, their positon and reputation on online platforms based on algorithms.

Income support for the self-employed

The COVID-19 situation has generated several challenges for the bogus self-employed. Because they are classified as self-employed, they have access to the government scheme, introduced in March to compensate the self-employed for loss of income due to COVID-19. The scheme includes a grant for three months equivalent to the 80% of the average profit recorded on tax returns (based on the previous year or the last three years if there has not been activity in the last year) up to a limit of £2,500 per month for all self-employed with profits below £50,000. The scheme has been renewed from July onwards but with a lower amount (up to a limit of £2,190 per month).

Although the grant is a big step forward and is generous and comprehensive in relation to other countries, several issues affect its accessibility and fairness.

The scheme is based on the annual tax returns of previous years and this penalises low paid workers and those who recently joined the sector, including those in sectors with a high turnover (for instance, app-based courier services) in which it is difficult to find workers with long tenure. Surviving on 80% of their income is unsustainable.

In addition, those with a profit of less than £1,000, who are not required to complete annual tax returns, are excluded. This means that some bogus self-employed workers cannot access the scheme at all. This includes those with low profits or, for instance, those affected by tax release schemes that do no report profits; for instance, foster care workers who are recruited as self-employed workers by agencies or local authorities.

The scheme started in March but payments from the first grant did not start until the 25 May, potentially leaving many workers with no pay for almost two months. Although they can claim Universal Credit, the access is means tested at household level and delays in payments of up to five weeks have been recently reported.

Health and safety

Another key element that has arisen relates to health and safety. During the COVID-19 crisis many bogus self-employed workers have been engaged in activities that involve high risks of contagion. Many have not received appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) from employers. For instance, the lack of PPE has been reported by construction workers, and couriers have demanded that the necessary PPE should be provided by the platforms that employ them. The negligence of employers/agencies/platforms in failing to provide protection measures and the lack of clear protocols is highlighted by a report from the Fairwork project about the platform economy responses to COVID-19. The report shows that very few platforms in the UK and globally have provided protection equipment.

Moreover, bogus self-employed workers also face significant difficulties due to their dependence on key contacts, agencies and platforms to keep their jobs. The risk of being removed from the platform or not being called again is one of the main barriers preventing these workers requesting more secure working conditions.

Reinforcing employers’ responsibilities

The UK has needed to develop emergency measures to cope with the consequences of COVID-19 due to the weakness of its social protection mechanisms. The crisis has revealed how the UK social protection system is designed to offer workers only the absolute minimum protections and does not provide a sufficient income when dealing with the event of illness, job or income loss. Although statutory sick pay has been granted to self-employed workers, its low amount (£94.25 per week) reveals the weak safety net that exists in the UK.

Although the extraordinary grant for the self-employed is fairly comprehensive the unclear status of bogus self-employed workers and their short tenure makes them extremely vulnerable in accessing it. The dependence that characterises this status makes it difficult for workers to access/request it due to the fear of eroding future job opportunities. Moreover, this also makes it difficult for workers to claim for safe working conditions and equipment.

There is an urgent need to recognise their dependence on clients and platforms as their employers, and measures should be developed to reinforce employers’ responsibilities towards these workers. Because individual employers tend to be reluctant to develop these responsibilities by themselves (for example in terms of health and safety or providing income protection to low paid workers), a stronger regulatory role of the state is required to enforce safe working conditions and to guarantee safe spaces for workers’ claims. This could be developed by making clients and platforms more directly responsible of the health and safety of these workers and by setting up employer-funded schemes to protect them during non-income periods due to specific contingencies. Furthermore, the enforcement role of the different agencies involved should be reinforced and more coordinated mechanisms should be developed. If not, the burden of the uncertainty that COVID-19 or other potential social crises could bring will continue to be paid by the most precarious and vulnerable workers.

Originally published 20 July 2020

Transport and logistics during the COVID-19 pandemic

Dr Sheena Johnson and Dr Lynn Holdsworth

While the majority of the population is urged to stay at home, the country is relying on the transport and logistics sector to maintain the delivery of goods, and most importantly food and medical supplies, which have seen a substantial increase in demand. People working in the haulage industry are identified as key workers given the importance of maintaining a supply network during the COVID-19 crisis and related lockdown in the UK. There has been, though, relatively little open discussion about how the situation is affecting the industry and its workers. Dr Sheena Johnson and Dr Lynn Holdsworth discuss the changes to the working environment in the sector, and the support necessary for drivers.

As part of our research into the health and wellbeing of the ageing workforce within the transport and logistics sector, we set up the Age, Health and Professional Drivers’ (AHPD) Network, which works to highlight the importance of protecting the health and wellbeing of professional HGV drivers. Professional HGV drivers are an ageing workforce exposed to a variety of health risks linked to the nature of their work. The transport and logistics sector was already facing driver shortages and a struggle to maintain driver numbers given the high proportion of older workers approaching retirement, and the limited numbers of younger drivers entering the workforce.

The AHPD Network now wants to focus a spotlight on the impact the COVID-19 crisis is having on the industry, and its professional drivers. We argue the current situation, alongside the ageing workforce and the health risks associated with the job, brings the perfect storm of issues that could negatively impact on the professional driving workforce. We asked AHPD members to tell us what the situation is like for them as the industry responds to the COVID-19 crisis and draw on some of their answers here.

Changes in guidelines

Changes in regulations intended to help with the flow of goods have been implemented in the transport and logistics sector in response to COVID-19, including:

· Relaxation of driver hours to allow drivers to work longer hours;

· Relaxation of driver training requirements;

· Rule changes meaning drivers whose qualification card expires between March and September can continue driving without renewal;

· The exemption of MOT testing for vehicles for three months;

· Temporary removal of routine medicals to facilitate renewal of driving licenses.

These changes are likely to have implications for the health and safety of drivers, and companies have to manage a fine balancing act to keep goods moving and protect their drivers.

Impact on companies

Companies have been disparately affected, with some reporting being run off their feet, especially those involved in food distribution. Online orders have also increased. Others though have seen their work dry up almost completely, with an estimate of nearly 50% of lorries currently parked up. Companies that are still moving goods have been affected by staff absences due to shielding, childcare or sickness. Whereas some companies have been able to provide full pay to individuals not able to work or have taken advantage of the Government’s furlough scheme, others have offered no more than statutory sick pay, which may encourage people to work whilst unwell for financial reasons.

Impact on individual drivers

The average age of a HGV driver is estimated at 57 years with about 13% over the age of 60. Professional drivers are recognised within the transport and logistics sector as comprising an older, and potentially less healthy, workforce due to some of the risks to health that are associated with the nature of the job. These risks include obesity, unhealthy diet, lack of exercise, exposure to stress and sleep deprivation or disturbance. Given the associated risks of COVID-19 to older individuals, and those who have underlying health conditions, this is a concern. A significant proportion of the workforce are absent from work due to adhering to shielding guidance or because they are experiencing symptoms associated with COVID-19, with reports of over a fifth of the workforce being absent in some companies. Other employees are still in work but fall into the vulnerable category meaning extra care must be taken to reduce the increased risk they face associated with contracting COVID-19.

In addition to reducing risks to physical health, it is important that companies remember to also place emphasis on mental health and wellbeing. Professional drivers are facing numerous challenges that could negatively impact on this. For example: concerns about contracting COVID-19; the extension of their working hours and increased work demands; increased isolation due to furloughing or whilst on the road and experiencing reduced contact with people due to social distancing measures; uncertainty about jobs, incomes and possible redundancy down the line; concerns about potentially increasing the risk to their family members if they are placed at increased risk whilst at work.

Looking after the workforce

Both employers and employees need support during this outbreak. Companies would benefit from the recommendations highlighted in the joint industry letter that has been produced, asking for more changes to protect the industry stating that the existing changes are welcome but not enough.

Both the Government and employers can support individual staff. Before the COVID-19 crisis the AHPD Network produced Health and Wellbeing Best Practice Guidelines, giving information and links to resources and support. These are arguably more important than ever as the transport and logistics sector responds to the COVID-19 crisis. Alongside the current changes in regulations, we urge the Government to remind companies of the importance of the health, safety and wellbeing of their drivers. We hope that the best practice guidelines provide concrete, practical recommendations that the Government can include in guidance for the industry during this time.

We further suggest that the Government make recommendations, both within the transport and logistics industry and more broadly to employers in general, to ensure the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on mental health is understood and employee mental health protected.

In addition to the best practice guidelines, we recommend that employers pay attention to:

· Adhering to specific guidelines linked to COVID-19, such as social distancing;

· Ensuring good communication is in place with drivers, now more than ever they can feel isolated from other employees. This should include furloughed employees;

· Placing increased emphasis on the protection of employee mental health. Mental health support can include the support already provided by a company and specific COVID-19 mental health support (eg Mind, the mental health charity has published COVID-19 related advice);

· Providing bereavement support.

Originally published 28 April 2020

Sharing the load: How work sharing can reduce unemployment, improve gender equality, and benefit mental health

Professor Jill Rubery

The need to build back better has received widespread endorsement, not only because the COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for change but also because it has revealed the high price paid by those facing inequality in the labour market, including inequality by gender. Here, Professor Jill Rubery, Director of the Work and Equalities Institute, discusses the importance of building gender equality into recovery plans from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Progress on gender equality may be reversed in the recovery from COVID-19 unless action is taken. Women have been more at risk of both job loss and furlough and the move away from furlough may rapidly increase the risk of job loss as employers can now determine not only if it is safe to return to work but also whether parents can be required to return even before the opening of schools and many nurseries. Indeed, despite the surprisingly successful teleworking experiment, the current message is to return to the prior normality. This is a missed opportunity to build on positive developments under the COVID-19 pandemic and to fix the gaps in the support systems for gender equality, some evident before COVID-19 and others emerging during or because of the crisis. While women may have been in the forefront of the key workers being clapped during lockdown, little is being done to improve their pay and conditions. Care workers with COVID-19 symptoms will still have to choose between surviving on around £95 a week statutory sick pay, one of the lowest in Europe, or risking their own and their clients’ lives by continuing to work.

Changes to employment status resulting in mental ill-health

Building gender equality into the path to recovery has many benefits, not only reducing the risk of wasting the talents of half the population but also of reducing risks of both adult and child poverty.

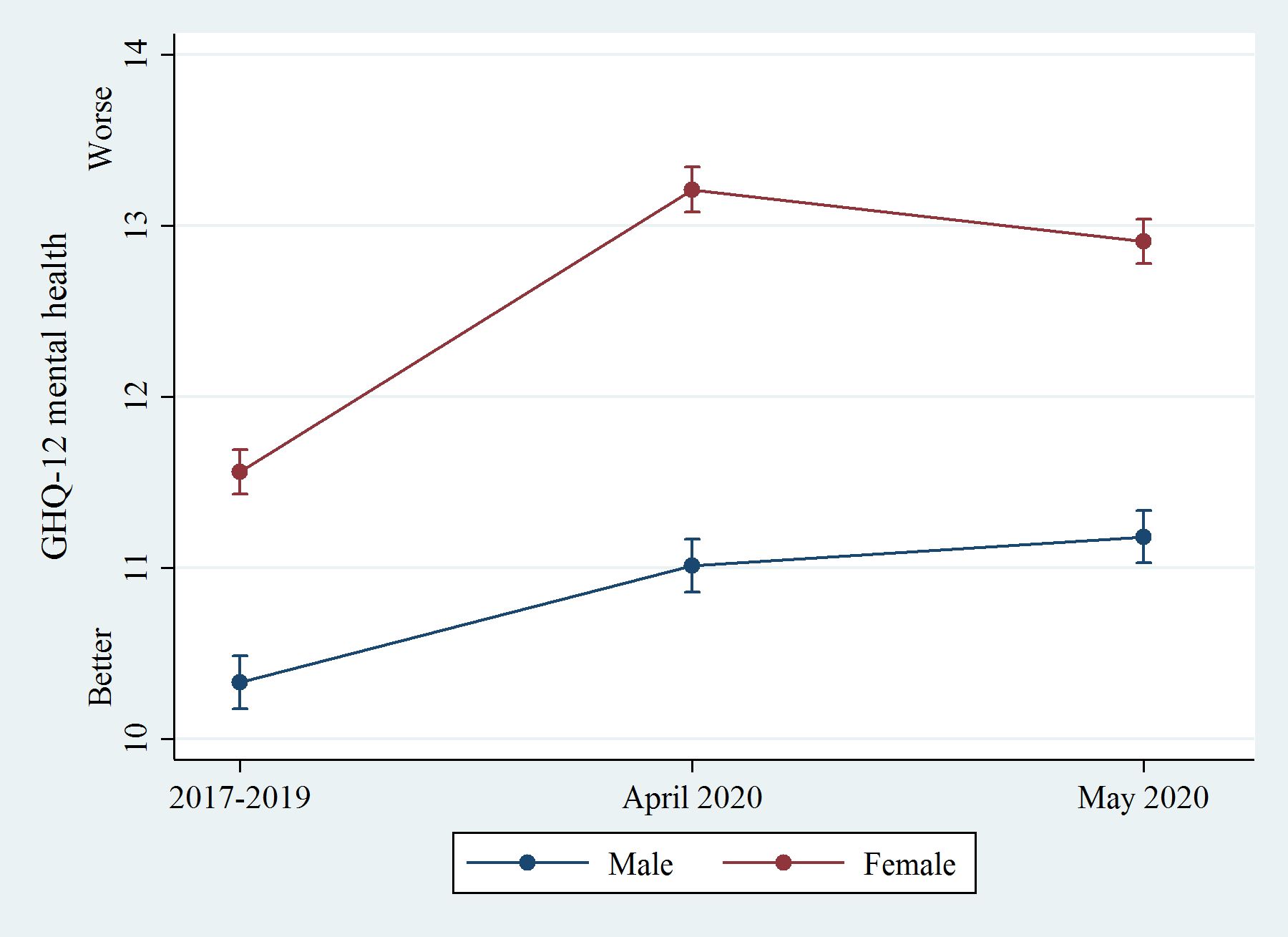

Yet another really important reason to focus on gender equality is to limit the risk of mental ill-health. A new analysis based on data for April and May 2020 from the Understanding Society survey (analysis by researchers from Cambridge, Salford, Leeds and Manchester) has found that although both men’s and women’s mental health worsened during the COVID-19 crisis, see Figure 1 it was women’s ill-health that rose most steeply. Moreover, for both sexes it was entering unemployment that had the worst impact on mental health of all the various options during the COVID-19 crisis – even worse than furlough or reduced hours of work. This indicates that mass redundancies could result in permanent damage to the mental health of the population.

Figure 3. Mental health rates for men and women in 2017-2019, April 2020 and May 2020 waves of Understanding Society

Source: Understanding Society COVID-19 Study

So is there an alternative? These experiences point the way to an alternative policy agenda that could reduce the risks of high unemployment and further deterioration in mental health while also promoting gender equality.

Reducing unemployment and promoting gender equality

To seriously reduce the risk of high unemployment and maximise job retention we need to use work sharing (or short-time work) across the whole workforce. Although those on furlough can start to work part-time from August the risk of redundancies would decrease if, in sectors and companies operating below capacity, all staff were, for example, to be put on the equivalent of a four-day week, including those who were kept on normal hours during lockdown. Short-time work is used in other countries and provides a more equitable route back to normal working, reducing the tendency to select people for redundancy just because they were on furlough. Companies using work sharing to preserve jobs could receive subsidies, perhaps enabling a higher level of earnings to be maintained. This would be much less costly than the furlough scheme while keeping more people active and attached to jobs, with all the benefits to mental health and wellbeing this provides.

This policy of work sharing could have a double benefit; not only would it enable a smoother and less risky transition out of furlough but it could also set the foundation for changing the gender division of labour across both paid and unpaid work. These dual benefits need to be recognised and promoted, perhaps through the aim to move to a maximum 30 hours of wage work per week. Without such a common objective there is a danger of reinforcing gender divides if in the future women’s jobs are organised as telework while men return to their offices. The COVID-19-induced experimental integration of work and care, often for both parents, has increased men’s engagement in childcare even if women have carried the main additional burden. To sustain work sharing across all groups, minimum hourly pay would need to rise, but this could have the positive spin-offs of improving pay for key workers, including care staff and boosting women’s relative pay in many households, in line with a more equal sharing.

Beyond work sharing

Work sharing will be ineffective where demand is low or where much of the work is part-time. It is necessary to complement this approach with job creation schemes and opportunities for retraining, but the current build, build, build agenda is too focused on the construction sector and by implication men’s jobs. Instead of only roads, we need to focus on rebuilding our damaged nursery sector and our elder care system.

Just as in Roosevelt’s New Deal, we also need to complement the demand-side policies with action to strengthen workers’ rights and plug the holes in the system of worker protection in the UK that have been revealed by COVID-19. Three holes particularly need filling:

· The first is to improve the very low statutory sick pay in the UK, lower than anywhere else in Europe bar Malta, resulting in by far the highest reliance on voluntary employer top-ups to statutory sick pay. In any second wave, it will still be women facing higher risks of infection and the dilemma of whether to follow the track, trace and isolate policy, and only 43% of employees in the care, leisure and other services sector receive above statutory sick pay.

· This problem is exacerbated by the second problem. That is the high number of employees – estimated by the TUC to be 2 million and 70% of them women – who do not even qualify for statutory sick pay or indeed unemployment benefits, namely those who do not regularly earn over £118 a week due to short hours, low pay or irregular employment such as zero hours contracts.

· The third hole in the protective floor is the lack of security for parents who end up having to care for children under local lockdowns or school closures. They may only be given unpaid leave for a period that it is up to the employer to determine as reasonable. Moreover, if childcare proves problematic due to the collapse of after school care, private nurseries or summer holiday camps, or frequent school closures, there is an increased risk that the share of women being made redundant or being forced to quit may rise still further.

Without new policies and protections, the danger is not only that we miss out on this opportunity for radical change but that we slip backwards into greater gender inequality, household insecurity and poorer mental health.

Originally published 3 August 2020

Recognising the role of key workers now and in the future employment landscape

Dr Gail Hebson and Professor Miguel Martínez Lucio

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the country has become more aware and appreciative of the workers now called ‘key workers’. However, organisational change and deregulation over recent years has led to high levels of job degradation in key work sectors. Here, Gail Hebson and Miguel Martínez Lucio introduce and present research from a range of colleagues and projects in the Work and Equalities Institute to discuss ways a greater appreciation of these key workers can be converted into jobs that are safe, well remunerated and attractive as careers.

Findings from our research with key workers show deterioration in working conditions for workers in these sectors.

Levels of pay and opportunities for training and development must be addressed, adequate sick pay is necessary, and it is essential that workers’ interests are represented and heard.

A policy agenda that converts symbolic recognition of these workers into a framework for decent employment conditions should now shape the post-COVID-19 employment landscape.

During the COVID-19 pandemic there has been a growing recognition that workers in sectors such as health services and care homes have played a vital role in sustaining the core services needed to protect and support the elderly and the infirm. In addition, a range of workers in retail – especially supermarkets, logistics and delivery, and gig-economy jobs – have played a vital role in ensuring the distribution and circulation of food and goods more generally. Moreover, cleaners in many sectors have come to be viewed as a vital component to any public response to a health crisis. These sectors can be considered part of the foundational economy.

Alongside clapping for carers, there was a general raising of awareness of how vital a wider range of jobs, which had been undervalued both politically and socially, were to sustaining the country during a context of crisis and social disruption. This was underlined by the deaths of key workers, whether health workers or bus drivers.

Engaging with key workers through research

For some time, the Work and Equalities Institute (WEI) at The University of Manchester has been carrying out research with key workers through a range of projects based on the care sector and cleaning services, as well as supermarkets and transport and logistics, that have come to the fore during the current pandemic. Much of this research has questioned where this work has been positioned within the common categories of ‘skilled’ and ‘unskilled’ work – a binary that is not always clear in its definition. It has also highlighted how organisational change and deregulation in such sectors has led to a high level of job degradation.

We have seen through such projects how employers use the practices of outsourcing, self-employment and the marginalisation of collective worker voice as a means of pushing down labour costs and creating a more flexible yet fragmented economy. In some cases, such workers have been employed from a vulnerable social and employment background – further undermining the chances of creating a more dignified and decent framework of employment as employers isolate and fragment the workforce.

Recognising key workers and their roles in the economy and society

A concern has begun to emerge that the shift in public awareness may remain symbolic and be usurped by a range of other political interventions. There is a need to sustain, and build on, the momentum of interest in valuing a broad range of work that has until now been taken for granted. WEI researchers submitted evidence to the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Select Committee inquiry in 2019 on Automation and the Future of Work, recommending how jobs in undervalued sectors, can be upgraded in both material and organisational terms to bring matters of dignity, rewards and fairness to the fore.

First, the levels of pay for such workers – in the context of a substantial deterioration in recent years – needs to be addressed so the nature of these jobs and their essential role in the functioning of society is recognised and becomes a reason that they are attractive to job seekers. There is a growing concern that such key positions – in both formally skilled and unskilled areas – have seen a general deterioration in working conditions that affect both the material conditions of the relevant workforce and the workers’ motivation. It also generates significant recruitment and retention issues, as sectors such as care homes are seen to consistently be poorly paid but highly work-intensive employment and record a high level of vacancies.

Second, some key workers appear to have been increasingly deskilled and downgraded although the more proactive aspects of their work have ironically increased, as with cleaners in key sectors. The changes in the care sector, for example, have created limited developmental opportunities and restricted time for training. There now does not seem to be a stable and effective path to career development as the sense of professionalisation the sector once had is steadily eroding. To that extent, many other key worker jobs – especially those not requiring a formal skill set – have been steadily fragmented and undermined through greater work intensification and ever greater recourse to subcontracting and employment agencies. In the context of care work, WEI research has found that the role of local authorities is increasingly important to regulate standards among outsourced care workers.

Third, we have seen short-term or zero hours contracts and the abuse of the ‘self-employment’ status by employers for their workers, limited sick pay arrangements and poor absence management. Delivery workers employed in the context of the gig-economy have been exposed to increased health and safety risk during the pandemic, with many excluded from mainstream employment rights protections due to bogus self-employment contract status .This has led to workers feeling that they need to keep working even when unwell, meaning that many clients may also be put at risk, especially during the pandemic.. This issue of increased exposure to health and safety risks in the context of the pandemic is particularly pronounced in sectors such as transport and logistics. Many of the key workers in this sector constitute an ageing workforce who already face a number of health issues which may be exacerbated in the context of the pandemic.

Fourth, many workers in sectors such as private transport, delivery and warehousing that have been important to the national response to the pandemic have nevertheless been deprived of a voice and a right to express their views on how their work should be managed and what their working conditions should be. Blatant attempts in such sectors to avoid trade union recognition and roles has demonstrated a need for rights to representation and worker voice to be developed and extended to those working in both the gig and the care economy. In addition, this voice and the body of rights has been weakened by the undermining of the inspectorate and enforcement agencies.

Looking ahead and building a greater appreciation of the role of key workers

If we are to build both a decent framework of employment for key workers and a more sustainable response to the challenges that natural disasters or pandemics bring, then we need to complement the symbolic concern for the status and wellbeing of such workers with a range of policies and instruments. These polices must ensure that these jobs are made safe, better remunerated and offer space for personal and professional development, and become more attractive as careers. They, along with all areas of employment, need to be socially supported by the state. Despite efforts made under the pandemic to extend some protection to the self-employed, many low-paid employees and bogus self-employed workers are still likely to have fallen through the safety net. Finally, such jobs should be the focus for open dialogue that allows such workers the right to raise a range of questions with regard to employment and the delivery of their services.

With special thanks to our contributors:

Kirsty Bagnall is Communications and Influence Officer at Ambition for Ageing, a Greater Manchester wide cross-sector partnership, led by GMCVO and funded by the National Lottery Community Fund, aimed at creating more age-friendly places by connecting communities and people through the creation of relationships, development of existing assets and putting people aged over 50 at the heart of designing the places they live.

Tine Buffel is a Senior Lecturer at The University of Manchester, where she directs the Manchester Urban Ageing Research Group (MUARG). She has published widely in the field of ageing, with a particular focus on issues relating to urban change and social exclusion in later life.

Aude Cefaliello is PhD Candidate at University of Glasgow. Aude's research focuses the development and regulation of occupational health and safety (OHS) on a European level.

Patty Doran is a Research Associate for the UK Data Service based in the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research at The University of Manchester. Patty’s research has focused on ageing, inequalities, social support and the life course, and using mixed methods to address complex research questions.

Tony Dundon is Professor of Human Resources Management and Employment Relations, Department of Work and Employment Studies, Kemmy Business School, University of Limerick; and Visiting Professor, Work and Equalities Institute, The University of Manchester.

Francesca Gains is a Professor of Public Policy and academic co-director of Policy@Manchester. Before becoming an academic she worked in local government & the probation service, and has both government funded and Parliamentary research experience. She is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and on the editorial board of the Journal of Public Policy, Local Government Studies and the International Review of Administrative Sciences.

Gail Hebson is Honorary member of the Work and Equalities Institute. She researches employee experiences of low paid work, job quality and equality and diversity practices in organisations.

Lynn Holdsworth is a Chartered Occupational Psychologist registered with the Health and Care Professions Council, and Lead Researcher and Network Co-ordinator for the Age, Health and Professional Driver’s Network. Lynn’s research interests include health and wellbeing, the ageing workforce, and empowerment.

Debra Howcroft is Professor of Technology and Organisation in the People, Management and Organisation Division of Alliance Manchester Business School. Debra’s research interests cover the area of ICTs and organising, particularly in relation to work and employment.

Cristina Inversi is Lecturer in Employment Law at the Alliance Manchester Business School and Research Fellow on FARm Project at Università Statale di Milano, Dipartimento di Scienze Sociali e Politiche. Her research focuses on labour regulation and working time.

Sheena Johnson is a Chartered Occupational Psychologist registered with the Health and Care Professions Council, and a Senior Lecturer at the Alliance Manchester Business School. Sheena set up the Age, Health and Professional Driver’s Network and her research interests include health, wellbeing, and the ageing workforce.

Camilla Lewis is a Senior Lecturer in Ageing and Urban Studies at Newcastle University. She joined in July 2019 from The University of Manchester, where she led an ESRC-funded project about ageing in place. She is a social anthropologist interested in interdisciplinary approaches.

Marti Lopez-Andreu is Lecturer in Human Resource Management and Employment Relations at Alliance Manchester Business School. He has researched issues of precarious work and employment insecurity, institutional and organisational change and employment and social protection.

Miguel Martínez Lucio is Professor of Human Resource Management at Manchester Business School. He has researched issues of workplace absence, health and safety, labour regulation and worker participation – amongst others – since the 1980s.

Jo McBride is a Senior Lecturer of Industrial Relations, Work and Employment at Durham University and the President of the British Universities Industrial Relations Association. Her research focuses on collectivism, social perceptions of the value of jobs and the causes and consequences of low paid work and multiple employment.

Chris Phillipson is Professor of Sociology and Social Gerontology in the School of Sciences at The University of Manchester. He has published extensively on issues relating to ageing in cities, and issues relating to the transition from work to retirement.

Jill Rubery is Professor of Comparative Employment Systems at Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester, and is a member of the Manchester Fairness at Work Research Centre.

Abbie Winton is a Doctoral Researcher at the Work and Equalities Institute. Her research considers issues surrounding sociotechnical change in the UK retail sector, with a particular focus on the widening of gender inequalities and the degradation of work and employment.

Sophie Yarker is a Research Fellow at the Manchester Institute for Collaborative Research on Ageing (MICRA). She has a background in human geography and sociology with research interests in community, belonging and civil society.

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Manchester.

August 2020

The University of Manchester

Oxford Road, Manchester

M13 9PL

www.manchester.ac.uk