OnGender

Analysis and ideas taking a gendered lens to policy

Foreword

Donna Hall CBE

It is my great pleasure to introduce this important publication into the gender agenda with implications for Greater Manchester and beyond. We all recall the now infamous image of ten white Greater Manchester men signing the devolution agreement with George Osborne, another white man from government, five years ago. The gothic splendour of the room in which the signing took place in Manchester Town Hall contains a similar though older photograph. The fathers of the city (all white men) are debating the poor laws. Not much has changed in over one hundred years. This exciting report, compiled by researchers at The University of Manchester who want to see this change, explores what actions we need to take to give women a voice in policymaking.

There has never been a more pressing need to speak out and to drive equality. Society is more fragmented than it has been for a long time and we have seen an explosion of vitriolic extremes. Austerity has had a serious and debilitating impact on communities both in Greater Manchester and across the country. Whilst the city centre of Manchester has enjoyed growth in jobs and housing to rent for upwardly mobile workers moving into the vibrant city, those furthest away have cripplingly low wage levels, whether they are male or female.

However, it is women and girls who are more severely affected by these disparities. As the statistics in this report clearly demonstrate, they are not able to benefit equally with men and boys from the economic growth seen within city-regions. This report highlights the gender dimension to welfare reforms, and with the majority of lone single parents being women, this group has suffered most from these policies. Quite simply, austerity has hit women much harder than their male counterparts. If you got a group of misogynists in a room and said how can we make this system work for men and not for women, they would not have come up with too many ideas that are not already in place.

A visit to a secondary school in Atherton when I was Chief Executive at Wigan Council really genuinely shocked me to my core. I was an adopted child of two factory workers brought up in Breightmet, Bolton and the first to go to university, etc... I spoke to five A Level students, all girls, all incredibly bright and predicted top grades but with zero self-confidence. I don’t know why but I thought things would have changed over the last forty years since I was in that same position. The school and the council had managed to find them two weeks’ work experience at PWC. They were not going. They had never been to Manchester and it would be too posh. They didn’t have the 'right clothes'. They went to Tesco for their work experience instead.

Increasing the confidence, the skills and the opportunities for all of our population is the only way devolved areas will achieve their full potential.

We have a lot to do to redress the balance and to ensure gender, race, childcare, sexuality and class are no longer barriers to progression and to an equal standing in communities. Today’s political leaders in Greater Manchester appreciate the distance we need to travel to ensure we don’t continue to hold back the full potential of over a half of our population. This publication provides research to support leaders across the country to consider policy through a gendered lens to address imbalance.

Getting gender on the devolution agenda

Professor Francesca Gains

The devolution of powers to local government in England since the first Greater Manchester deal was signed in November 2014 has resulted in further key responsibilities and funding being devolved. Following the Cities and Local Devolution Act 2016 nine areas have agreed devolution deals, eight of them headed by an elected metro mayor. The type of funds devolved and the policy agendas covered vary deal by deal, as does the extent to which combined authority areas use fiscal powers to raise funds through business rate retention, supplements and an additional council tax precept. A devolution framework is awaited and details of many deals are not publically available. However, it is clear that significant decision-making powers and funding have been granted to combined authorities and metro mayors. The ability to set policy agendas and commit resources means devolved powers are increasingly important for the citizens and communities in many densely populated urban areas in England.

For the politicians and metro mayors in these areas, devolution offers opportunities to use their powers to achieve economic and social improvement for their communities. The Greater Manchester Combined Authority home page shares a vision for Greater Manchester to be “one of the best places in the world to grow up, get on and grow old”. There is no doubt that the region’s politicians and policymakers have a passionate and long-held aspiration to improve the life chances of all Greater Manchester’s citizens and a commitment to inclusive growth. As the GMCA refreshes its Greater Manchester Strategy (Our People, Our Place), and where other combined authorities develop their local strategies, it will be crucial to understand the nature of inequalities in their region to target action and to monitor progress. As part of this policymaking process – now devolved from Whitehall – it will be essential to understand the importance of how gender inequalities affect localities and regions, and how the experiences and outcomes of men and women differ in the policy areas where devolved decision-making can make a difference.

Another century of gendered inequality

For 101 years after women first got the franchise and nearly four decades since the Equal Pay Act and the Sex Discrimination Act, as the British Council reports, nationally there still remain major gender differences in life chances; for example, in the levels of women’s representation in politics, through to employment opportunities and involvement in caring responsibilities and in significant gender pay gaps. Recent reports from the Office of National Statistics show that life expectancy for women in poorer areas is falling, and from the House of Commons Library that austerity measures have hit women harder due to their greater dependence on welfare and employment in low-paid part-time work, in addition a disproportionate number of women are the victims of domestic violence.

So, as the decision-makers and politicians in localities with devolution deals make plans to address the uneven life chances of their citizens, a focus on gender inequalities and getting women’s voices heard in policymaking is essential. Including women’s voices and their experiences (in all their diversity) is key to addressing inequalities and unlocking talent.

The need for better representation and better data

Having women around the policymaking table helps to bring to the fore issues that need addressing to tackle gendered discrimination. Female police and crime commissioners are twice as likely to make violence against women a priority. Crucially, where commissioners who take their equalities duties seriously – and look at the evidence on gender inequalities and women’s experiences of crime – commissioners both male and female are even more likely to have a priority focus on violence against women. As with the policing agenda, having women involved in decision-making and having a focus on the evidence base is equally important for the other key policy agendas addressed in devolution deals.

But the data available on how gendered inequalities play out in various policy areas is patchy. And interpreting the data requires nuance: women are not a homogenous group, inequalities are intersectional and gendered inequalities are also faced by different groups of men. To address this gap I brought together contributions from academics working at The University of Manchester to provide an evidence base for the Greater Manchester Women’s Voices Task and Finish Group on the representation of women in politics and policymaking in Greater Manchester. This evidence base highlights inequalities across the policy agendas that devolved authorities are working on. It also shows that the gender inequalities faced are not uniformly found. There is diversity in the gender risks identified here arising from ethnicity, from the employment sector, from geography – differences that are important to identify if policy action is to be effectively targeted and monitored.

Setting a new agenda

To address the gendered inequalities in devolved policy agendas it is vital to capture the diversity of experience in giving women a voice – through policy dialogue and better representation. Together with a closer examination of the equality and diversity evidence base, there are clear policy implications for localities with devolved deals who want to address gendered (and other) inequalities. This might involve strategies and actions in how they set their own policy agendas around education, skills investment, transport, housing, health and crime. And also through encouraging and working with local partners and stakeholders - employers, businesses and the third sector.

Policies which address educational and occupational segregation are needed to support girls to take STEM subjects and move into the higher paid and higher skilled occupations and employment in sectors such as construction, engineering and IT. Investment in skills and infrastructural support such as transport and childcare and the adoption of working practices such as flexible working would allow women to maintain their engagement in the labour market and would unlock increased productivity. Increasing the adoption of the voluntary (real) living wage in the health and care sector and foundational economy would support women and low income households. Listening to the experiences of the victims of crime suggests different and innovative ways of partnership working around the needs of women facing domestic abuse. Targeting support to particular communities, and working with marginalised groups is important to address the needs of women who face intersectional inequalities and in particular localities.

Metro Mayors, authority leaders, and police and crime commissioners – like all public officials – have equalities duties, and are charged with ensuring inequalities are considered in the design of policies and the delivery of services. As the first area to enter a devolution deal, the experience of Greater Manchester in addressing equalities duties can help to set the agenda more widely. To get gender on the devolution agenda, it is essential for all political leaders to ensure there is a diversity of voices around the decision-making table and establish equality impact assessment and equalities as a component of policy evaluation.

Gender disparities in education

Professor Ruth Lupton

In the English education system, there are significant gender inequalities, but not in the direction we are used to seeing. Up until the mid-1980s, boys enjoyed greater success than girls, but since then the tide has turned. Now girls do better in tests of academic achievement at every stage of education from early primary school to entrance to higher education. They are even ahead in teacher-assessed measures of early childhood development at the end of the reception year (aged 4-5). It’s important to note as well that boys are over-represented among those excluded from school, and not in education, employment and training (NEET) between the ages of 17 and 18. They are more likely than girls to be identified as having special educational needs.

These ‘boy problems’ or ‘girl successes’ are present across all social class groups and ethnicities. But we also need to recognise the multiple advantages or disadvantages that accrue through membership of multiple social/ethnic groups – the phenomenon of ‘intersectionality’. For example, while the ‘gap’ between boys and girls in GCSE attainment (good passes in English and mathematics) in 2018 was around 7 percentage points, the gap between boys eligible for free school meals and from a white British ethnic background and girls not eligible for free school meals from an Indian background was over 50 percentage points.

And we also can’t assume that the opportunity gaps for girls have been erased. Boys still dominate in subjects like mathematics and engineering, ones which have some of the highest returns to graduate earnings. In ‘vocational’ courses, young men dominate construction while young women predominate in health and care subjects.

All of these gaps will be of concern to politicians as they try to increase levels of ‘school readiness’ and ‘life readiness’, close disadvantage gaps, meet skill shortages in high-tech industries as well as revalue work in personal care occupations. Two things may help. One is that all the statistics are widely available. There is no excuse, in education, for not knowing about gender disparities. The other is that Greater Manchester is really no different from the rest of the country. Politicians in Greater Manchester do not need to feel they are playing a game of catch-up, so it is easier to ask the question: could Greater Manchester pave the way in tackling some of these gender disparities, demonstrating success to other areas?

Explanations and actions

This points to two suggestions for action. One is that Greater Manchester’s new Education and Employability Board, which has tasked itself with championing those who are least well served by the education system, should specifically address gender disparities and what it might do about them. The same might also be said for the School Readiness Board and Skills Advisory Panel. There is no reason, given the availability of data, not to keep this issue in view.

The other suggestion relates to what might be done and prioritised. Of course there are many explanations for girls’ greater educational success. Some focus on assessment and modular examinations, which are said to play to girls’ strengths. Some point to changes in the labour market and boys’ occupational identities. Some suggest that more routinised pedagogies and ‘teaching to the test’ positions boys as disruptive, which may position them as failures and increase their disengagement.

Other work asks us to question stereotypes of boys and girls and examine ways in which parents and teachers may reproduce gender differences through their practices. For example, Moss’s ethnographic study of a primary school showed that girls and boys read in different ways. Reading was more of a social activity for girls, while boys who read for pleasure were more likely to do so alone, and depended on family encouragement. Less proficient boy readers chose non-fiction texts more often because they could use images to engage with the texts and demonstrate subject knowledge, while less proficient girl readers might read easier texts with more proficient friends, thus building their reading skills. Moss and Washbrook also demonstrate interesting early differences (at age 3) in ‘pre-literacy’ activities with parents, with girls more likely to be sung to or taught the alphabet than boys.

Making the system work better

None of this will be new to educationalists working with gender issues, and the examples here give just a flavour of the large volume of research on this topic. There are no doubt multiple examples across Greater Manchester of creative solutions developed by individual teachers, school leaders, and early years professionals, whether these involve de-gendering classrooms, challenging assumptions, changing curriculum materials, bringing in role models, changing careers advice, arranging work placements, and working with parents and community groups to address gendered practices and expectations.

As is often the case, finding ways to capture and exchange these ideas is likely to be the key to change. As Professor Mel Ainscow, former head of the Greater Manchester Challenge and now Chair of Greater Manchester’s Education and Employability Board, has argued in his book Towards self-improving school systems, we need to be able to “move knowledge around” in an increasingly fragmented system. But GMCA can also set high-level examples, for example, building gender targets into skills strategies and pathways (such as digital and construction skills) and working with suppliers and contractors to help them build links with schools and community groups to help meet these.

Gender and occupational segregation in Greater Manchester

Anna Sanders and Professor Francesca Gains

Two key recent reports have highlighted trends in the Greater Manchester employment market. The Independent Prosperity Review highlights areas to boost productivity and increase prosperity across the region. Meanwhile, the Resolution Foundation’s Low Pay in Greater Manchester report provides an in-depth insight into Greater Manchester’s low-paid workforce. While both reports provide an invaluable insight into the Greater Manchester employment market, they lack a specific gender focus on occupational structure. More could be said about the gendered patterns of Greater Manchester’s labour market and its impact on prosperity and productivity.

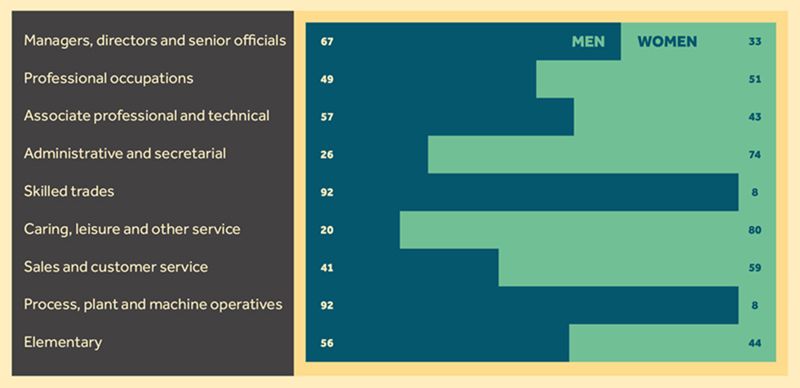

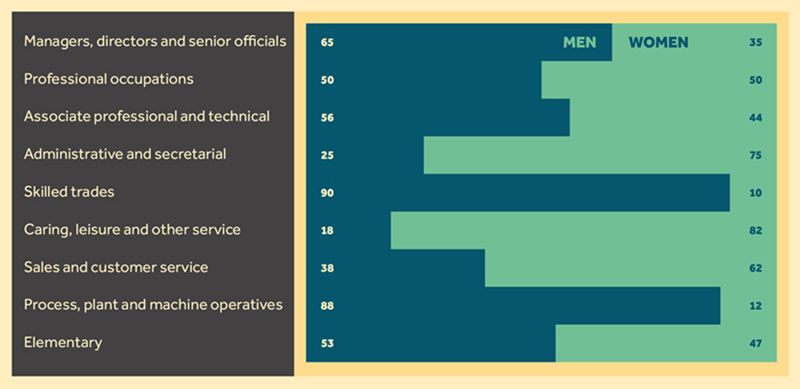

Figure 1 represents occupational breakdown by sex in Greater Manchester for 2018. Men are concentrated in higher-paid occupational sectors. Two-thirds of managers, directors and senior officials in Greater Manchester are men. Skilled trades and process, plant and machine operatives are also heavily male-dominated sectors. At the same time, Figure 1 shows that women continue to be overrepresented in traditionally domestic and ‘feminised’ sectors, outnumbering men in caring, leisure and other service occupations by four to one. These sectors are often low-paid, particularly in Greater Manchester: around one in five (19%) of employee jobs in health and social care in Greater Manchester are low-paid (compared to the national figure of 10%). The Resolution Foundation reports that women comprise the majority of those in low-paid employment in Greater Manchester (58% vs 48% of non low-paid employees).

Figure 1. Occupational breakdown by sex in Greater Manchester (2018). Source: Annual Population Survey (accessed via Nomis). Standard Occupational Classification 2010.

Figure 1. Occupational breakdown by sex in Greater Manchester (2018). Source: Annual Population Survey (accessed via Nomis). Standard Occupational Classification 2010.

Looking at Greater Manchester overall may mask variation between local authorities. Within the Annual Population Survey, it is not possible to break the data down further by each local authority. However, we can compare occupational patterns in Greater Manchester to the UK average. The picture in Greater Manchester is broadly similar to that of the UK at large (Figure 2), and shows that the concentration of men and women in traditionally ‘gendered’ occupations is widespread.

Figure 2. Occupational breakdown by sex, UK rate (2018). Source: Annual Population Survey (accessed via Nomis). Standard Occupational Classification 2010.

Figure 2. Occupational breakdown by sex, UK rate (2018). Source: Annual Population Survey (accessed via Nomis). Standard Occupational Classification 2010.

Changes over time

Women have traditionally been more likely than men to work in administrative and secretarial positions. The proportion of women working in such positions in Greater Manchester has decreased over time, but still remains high in comparison to men. In 2004, around 23% of female employees held administrative and secretarial positions, compared to just 6% of male employees. By 2018, around 17% of female employees were employed in the administrative and secretarial sector, compared to 5% of male employees.

Similarly, while the share of male employees working in skilled trade occupations in Greater Manchester has decreased over time, men continue to be overrepresented in this sector. Approximately 20% of male employees worked in skilled trade occupations in 2004, compared to just 2% of female employees. The poor representation of women in this sector has remained stagnant, with 2% of female employees working in skilled trades occupations in 2018. By 2018, 16% of male employees held roles in skilled trade occupations. Such decline is partly due to net job losses - particularly among male employees - in skilled trade occupations after the 2008 financial crisis. Additionally, research by the Resolution Foundation finds that the decline is also linked to fewer younger workers entering skilled trade industries.

Finally, the share of female employees working in caring occupations increased after the onset of the recession. Following the financial crisis and growing demand on care services, the sector has witnessed growing casualisation, leading to increased job insecurity. In 2014, the Burstow Commission estimated that, nationally, 60% of the home care workforce was on zero-hours contracts. The national picture is likely to be replicated in Greater Manchester, with implications for women’s employment conditions and job security, since they comprise the majority of those in the caring sector.

Key messages

Occupational segregation persists. Sylvia Walby and Wendy Olsen’s national report points out that occupational segregation limits women’s potential in the labour market, and has implications for productivity. Policy action to address these inequalities should encourage women to enter occupational sectors in which they are currently underrepresented, such as process, plant and machine occupations, or skilled trade occupations. At the same time, attempts should be made to attract more men into occupational sectors in which they remain underrepresented, such as caring and leisure services, or administrative roles. Policymakers should work with local employers, schools, and further education providers to open up apprenticeships and job opportunities for school children and young men and women.

Additionally, policymakers should work with public and private sectors in the region to address the precarious employment circumstances of women (and men) in occupations in the foundational economy and social infrastructure.

Take a look at further Policy@Manchester analysis on occupational segregation.

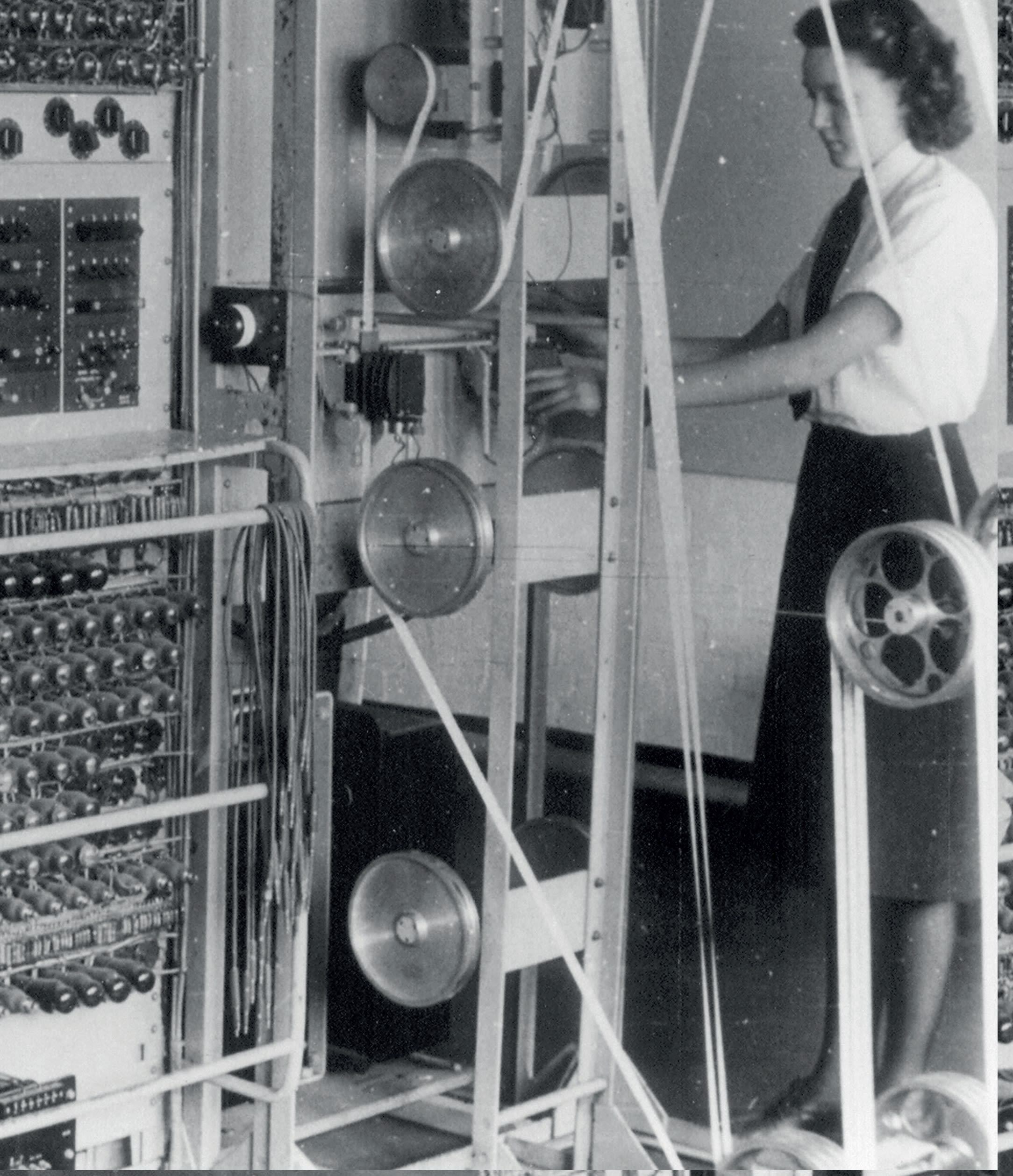

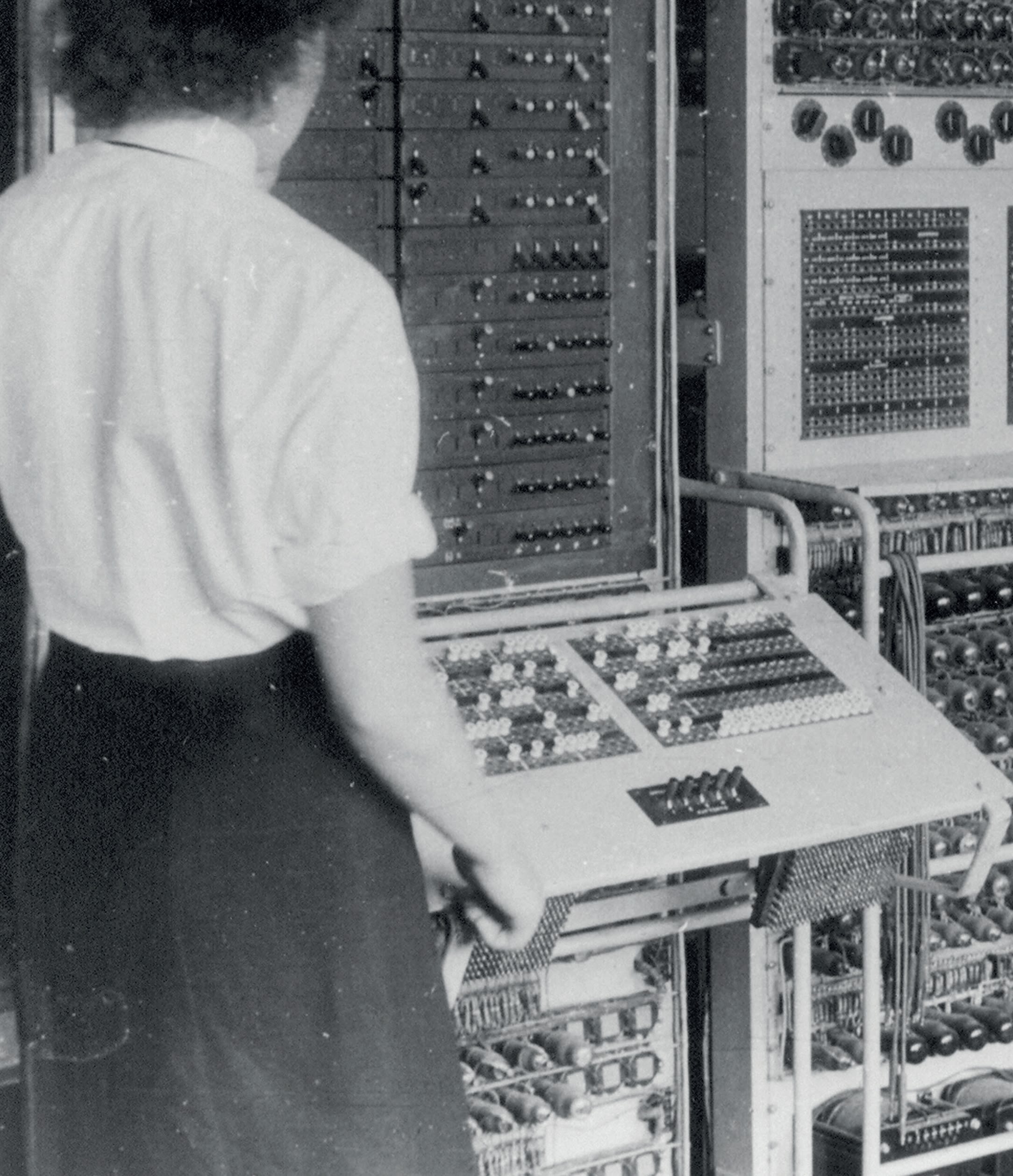

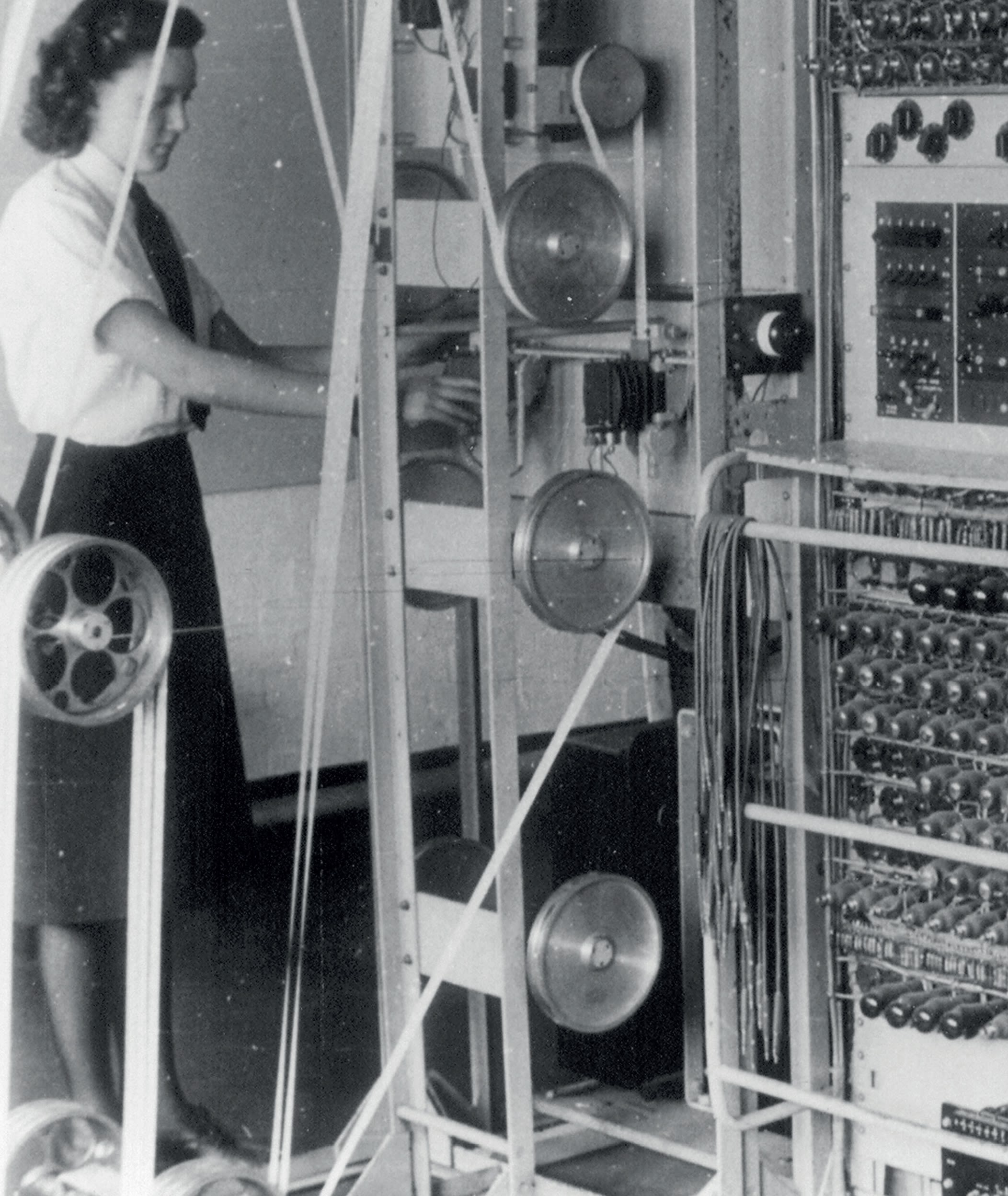

Striving for gender balance in the IT industry

Professor Debra Howcroft

Technical knowledge and expertise have long been associated with masculinity, but this has not always been the case. In the UK, the post-war computer industry was dominated by women working as machine operators, but by the 1970s, the technologically-minded female workforce were no longer welcome, becoming side-lined as the potential of computing began to be realised; women were phased out and replaced by higher paid men with better job titles.

Over the last 20 years or so, advances in digitalisation led to grounds for optimism - particularly as women have more access to a wide variety of ICTs. Yet, the IT industry remains riddled with gender inequalities. The enduring under-representation and marginalisation of women in technology occupations and professions is becoming more severe. There are decreasing levels of female employment in ICT professions (in the UK, this has reduced from 18% in 2016 to 17% in 2017) and those women who are employed in the sector tend to be concentrated in lower-paid jobs. IT developers consist of predominantly young male workers with ‘zero drag’ (highly motivated with little personal responsibilities and flexible working availability) who are inclined to work long hours. The ‘computer geek’ stereotype is pervasive and is associated with dedication and doing whatever is required - characteristics which are deemed ideal for working in an industry where delays and overruns are common.

Brotopia

While forecasters of a jobless future rarely agree as to how this will play out in practice, one area of consensus centres on the expansion of the technology sector. This is of concern when the people who design and develop technology are unrepresentative of society: tech firms employ few women, people of black, Asian and ethnic minorities (BAME) and people aged over 40. If technologies of the future are developed by a particular demographic, they are likely to reflect their worldviews. This lack of representation perpetuates the reproduction of inequality since competence in technology design and development often leads to command of higher incomes.

In the tech industry, the lack of diversity and ‘missing women’ problem is so entrenched that various policy responses have attempted to address this. Most of the initiatives are based on an ‘add women and stir’ approach, which barely scratches the surface. Consequently, numerous equal opportunity recommendations – largely based on sex-stereotyped assumptions – have failed.

For women working as a minority in the industry, dominant male work practices have been likened to frat house cultures and labelled ‘Brotopia’. This has led many women to vote with their feet and exit hostile work environments within a couple of years of being appointed. The prevalent macho dynamic has been amplified in numerous discrimination and sexual harassment cases in Silicon Valley, which suggest that this environment is far from ‘female-friendly’.

The GMCA Digital Strategy aims to tackle growth and productivity by achieving a gender balance in digital companies. This is especially relevant to GMCA given Manchester’s position as one of the creative capitals of the UK. Current figures show that in 2016/17, the ratio of men to women of those employed in technical roles in Greater Manchester was 79:21. The Digital Strategy aims to redress this gender imbalance and has set two key targets: achieving 60:40 by 2020, and 50:50 by 2025. While these aspirations are laudable, setting such ambitious goals will entail serious challenges given the gendered nature of the IT sector.

A ‘technology problem’

Given the endemic gender inequities within IT work, rather than focussing on targets which aim to level up gender representation, an alternative approach could involve tackling endemic inequalities from the bottom up.

A key challenge is not simply about increasing the number of women entering the profession, but about retention and progression. The challenge will involve removing embedded gender discrimination in working environments where women aim to build a career. Rather than expecting women to adopt a more masculine identity in order to fit in and succeed, the sector needs reshaping to accommodate women, so that it is no longer a ‘women problem’ but a ‘technology problem’.

Changes needed

To attract more women to the industry and increase retention, more equitable models of working, such as a shorter working week, job sharing, enhanced parental leave and a reduction in wage inequalities could help challenge some of the gendered boundaries in the workplace that shape the perceptions of employability and promotion. Expectations of excessive working hours - particularly around periods of ‘crunch time’ - need to be re-configured. Fluctuating demands are especially problematic for primary carers. Working in an industry with fast-paced technological change means that higher salaries are associated with those working at the cutting-edge. Given that the IT sector is characterised by start-ups and small enterprises, there is limited opportunity for training and career development during the working day. Instead, there is an expectation that ‘keeping up’ lies with the individual. Consequently, those with care responsibilities find it hard to progress, and those requiring a career interruption find it especially difficult to re-enter the labour market.

As the Digital Strategy shows, it is imperative that efforts are made to reduce gender inequalities within the IT sector. However, this approach needs to be combined with other resources that intend to correct the gendered nature of the workplace. As we have no local knowledge of the issues, in order to understand how to best provide concrete support and implement strategies for change, it is critical that we hear about front-line experiences from workers in the tech industry. This is vital if Greater Manchester aims to pave the way and reduce the inequalities within an industry deemed critical to the future.

Ethnicity and gender in the Greater Manchester labour market

Professor Ruth Lupton

The term ‘labour market inequalities’ refers to differences between social groups in the extent to which they are able to access formal employment and pay. In the UK, there remain very wide labour market disparities between ethnic groups.

The intersection between gender and ethnicity

Our research demonstrates, however, that there is a need for a gendered approach to this problem as well as an overall one. In Greater Manchester, employment rates for males aged 16-64 vary between ethnic groups but not by an enormous amount. Around 75% of white men are employed while for the larger minority groups (for whom estimates are more reliable) rates are between 68% and 72%. Of course, these figures do not tell us about the type of employment and pay.

For women, the pattern is very different. White women have the highest employment rate (71%), while for most other groups rates are much lower (52% for black/black British and 39% for Pakistani/Bangladeshi women – the group that also has by far the largest gap between men’s and women’s employment). Low employment rates for women are largely driven by low economic activity, particularly caring for home and family, and while this is partly a generational issue and trends are changing, it is not wholly so. Economic inactivity for Pakistani/Bangladeshi women aged 25-49 (nationally) is still three times as common as for white women. Meanwhile black women have the highest unemployment rates of all women.

What can be done to change this?

Our initial work with the Runnymede Trust suggested that the explanations for these disparities are complex and they demand multi-faceted responses. Employers need to tackle the under representation of women in particular occupations, increase opportunities for flexible working and avoid gendered stereotypes which may be particularly applied to minority ethnic women. In order to tackle higher inactivity rates among BME women there should be a focus on facilitating choice, for example, increasing provision of high-quality childcare, increasing mentoring for young BME women and working with parents to challenge ideas around gender and raise awareness of available opportunities.

Some of the data we need to address these issues is available, in the form of major national datasets such as the Annual Population Survey and decennial Census of Population. They just need to be taken more seriously in setting objectives and targets at a local level and in the Greater Manchester Strategy. But there are also many data gaps, particularly for smaller groups, for example, newly arrived refugee and asylum seeker groups, which need to be filled by local data collection. We have no local knowledge of issues of gender/ethnic pay or progression within firms and there are good reasons to ask larger employers to extend their legally required gender pay monitoring in this direction. In general, too, given the complexity of the economic, spatial, social and cultural issues that shape these patterns, it is vital to hear about the experiences of more marginalised groups and the ideas they have about what would help them. Voices of minority ethnic girls and women need to be heard more as well as more data collected about them. Our work suggested that this demands working alongside community groups as well as employers, and giving adequate resource and support to the community and voluntary sector to mobilise this knowledge effectively.

The gender pay gap in Greater Manchester:

What it tells us and what it doesn't tell us about gender equality

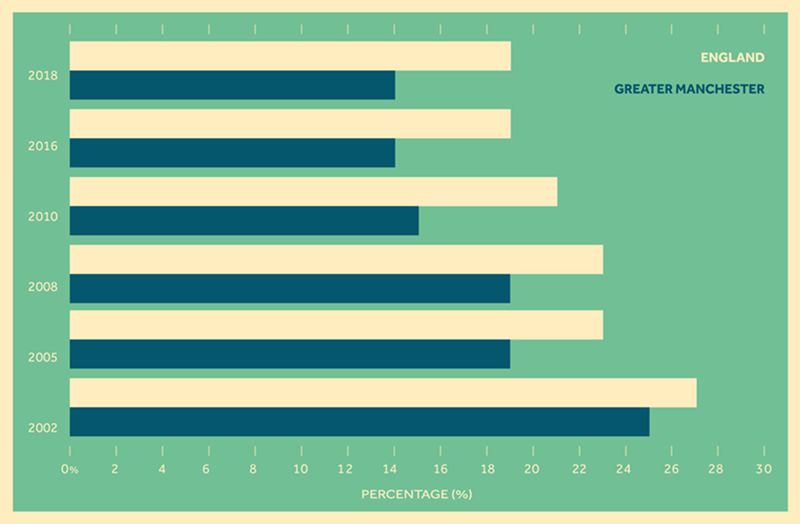

Professor Jill Rubery

A key indicator for gender equality is the gender pay gap. At first glance, the data appear to provide good news for Greater Manchester: the gender pay gap is below that found for England as a whole. The gap in median earnings for all employees of working age is 14%, 5 percentage points below that for England at 19%. In 2002, the gender pay gaps for Greater Manchester and England were only different by two percentage points, but the gap has subsequently widened, reaching 6 percentage points in 2010. The narrower gap in Greater Manchester compared to England as a whole is not, however, due to higher pay for women, but instead to lower relative pay for men. Women’s median pay in Greater Manchester is approximately 5% less than the median for England but men’s median pay in Greater Manchester is approximately 10% below that for England.

The consequence of men faring worse in Greater Manchester is that women’s earnings are likely to contribute more to family and household income in Greater Manchester than for the country as a whole. The gender pay gap is also an average measure and does not tell us much about what is happening for groups of women at different ages, with different skills, living in different locations.

To explore these issues further, we look at what is happening at both the bottom and top ends of the labour market and how this may be impacting on gender pay gaps and overall gender pay equality.

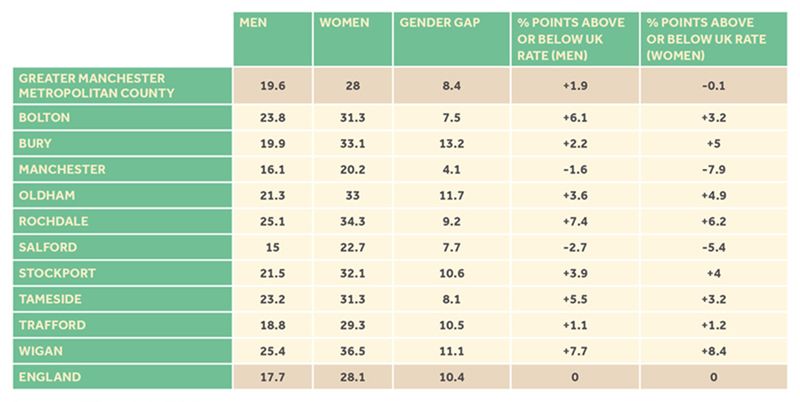

Risk of low pay

When we look at the risk of receiving low pay, we find that the share of men in Greater Manchester being paid on adult rates below the voluntary living wage is 19.6% - 1.9 percentage points above the share for men in England at 17.7%. For women in Greater Manchester, the share is 8.4 percentage points higher than for men at 28%. This is in fact almost the same – just 0.1 percentage points below the average for women in England. The gender gap in shares earning below the voluntary living wage is in fact two percentage points higher in England than in Greater Manchester at 10.4 percentage points.

This apparently positive picture for women is not found in all areas in Greater Manchester when we look at the data by local authority. Manchester and Stockport record lower risks of low pay for both sexes than the average risk for England, but all eight other areas record higher risks. Rochdale and Wigan have the worst records for both sexes, accounting for over a quarter of all men’s jobs and over a third of women’s. The gender gap in risk of being paid below the voluntary living wage is also above the national average in five of the ten local authority areas. What we find then is that although women are still bearing on average by far the higher risk, place of residence is also a major factor. In fact, the share of men being paid below the living wage in Rochdale and Wigan exceeds the share of women in Manchester and Salford.

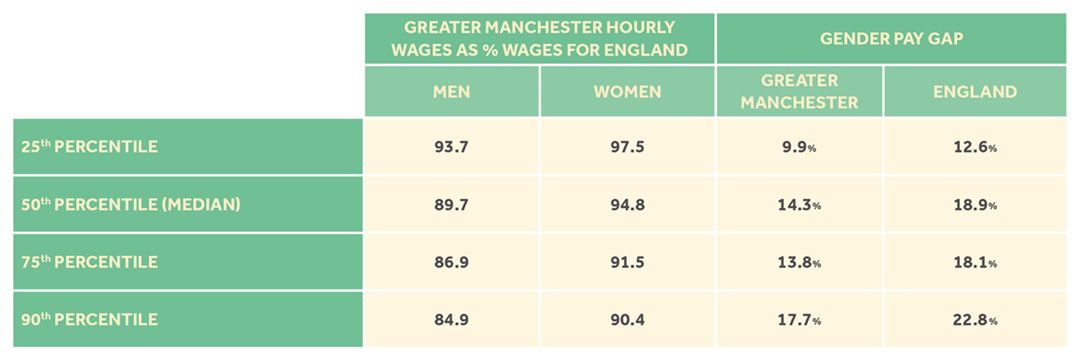

Opportunities for higher pay

So far we have been looking at the gender pay gaps for both low paid and median workers, but gender equality also depends on access to higher paid jobs. In much of the reporting on the gender pay gap, it is inequalities in access to higher ranks within companies that has attracted media attention. We do not have the data for investigating that here, but what we can see is an increasing gap between wages in Greater Manchester and the wages in England once we move up the pay scale. This implies that there are shortages of higher paid jobs in Greater Manchester – possibly in part accounted for by a smaller share of the higher skilled in the workforce, but differences in the availability of higher paid jobs undoubtedly plays a part.

What is interesting is that, even though as we move up the distribution of wages there is an even greater gap for men than for women between wages in Greater Manchester and England, the gender pay gap also widens. Men in Greater Manchester are falling further behind men in England as a whole, but their pay is still rising relative to women’s in the higher end of the labour market. At the 90th percentile, the gender pay gap rises to nearly 18% in Greater Manchester, but to nearly 23% for England as a whole, well above the 14% and 19% gaps found at the median level. Meanwhile, women’s wages in Greater Manchester at the 90th percentile are around 10 percentage points less than for England as a whole, but for men, the discount is over 15 percentage points.

Higher skilled women are particularly reliant on the public sector for access to higher level jobs; around three fifths of all women in employment with a university degree work in public services, including public administration, education and health and social care. The Greater Manchester economy has been rebalancing away from the public sector over the past decade due on the one hand to cuts within and outsourcing from the public sector and, on the other hand, to growth in the private sector. Numbers of jobs in the public sector have remained at roughly the same level over the past decade despite population growth, but jobs in the private sector have grown by around 13% for men and 16% for women. The public sector tends to pay notably higher wages for women due to the highly skilled composition of the workforce, and also offers more opportunities to work part-time in higher level jobs. However, since 2010, there has been a decline in both job opportunities and pay in the public sector, with particularly negative consequences for women who make up most of the workforce.

Key messages

There are three issues of relevance for the Greater Manchester social and economic strategy. The first is that promoting the adoption of the voluntary living wage could have a major impact on women’s earnings, particularly those residing outside the central area where the share earning below the living wage often accounts for a third or more of all women in work. This policy promotes gender equality, but also benefits the many low paid men in Greater Manchester and the many poor households that increasingly rely on women’s earnings to make ends meet.

The second message is that Greater Manchester needs to expand the number of high-skilled and high-paid jobs in line with Greater Manchester’s strategy, but there is a danger that this could further exacerbate gender pay inequality if the main beneficiaries were to be men. The gender pay gap widens at the top of the distribution even though men’s wages in these higher levels are much less than found for the nation as a whole. A policy to expand opportunities to women is thus vital to ensure against widening gender pay inequality.

Thirdly, more needs to be done to re-establish good pay and conditions in the public sector, and also in outsourced public services. These areas of employment are particularly important for women. Public sector pay and conditions are primarily set at national level, but more can be done at local or regional level to improve conditions for workers in outsourced services through commissioning policies.

Figure 1. Gender pay gap for Greater Manchester and England 2002-2018. Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) (accessed via Nomis) - median hourly pay excluding overtime (author's own calculations)

Figure 1. Gender pay gap for Greater Manchester and England 2002-2018. Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) (accessed via Nomis) - median hourly pay excluding overtime (author's own calculations)

Figure 2. Share of men and women paid below the voluntary living wage set by the Living Wage Foundation (% on adult pay rates). Source: ASHE analysis 009211

Figure 2. Share of men and women paid below the voluntary living wage set by the Living Wage Foundation (% on adult pay rates). Source: ASHE analysis 009211

Figure 3. Variations along the wage structure in Greater Manchester - by relative wages and the gender pay gap. Source: ASHE hourly earnings excluding overtime (accessed via NOMIS) (author’s own calculations)

Figure 3. Variations along the wage structure in Greater Manchester - by relative wages and the gender pay gap. Source: ASHE hourly earnings excluding overtime (accessed via NOMIS) (author’s own calculations)

Fathers and care

Dr Helen Norman, Professor Colette Fagan and Dr Nina Teasdale

Women do most of the work involved in looking after children and other family members. In the UK mothers spend more than double the amount of time on childcare than fathers. There is no regional data for time spent on childcare but the situation is likely to be similar for families across city-regions due to the design of national work-family policy combined with the lower earnings of women. Although attitudes about gender roles are changing – with many UK fathers agreeing that they should be as involved in the child’s upbringing as the mother – childcare responsibilities between parents remain unbalanced.

Work-family policy

So, why are fathers less involved in childcare? One reason is due to national policy, which focuses on helping mothers rather than fathers to adapt their employment hours and schedules after having children. This will affect how families arrange work and care.

- Mothers are entitled to take up to a year of maternity leave (39 weeks at Statutory Maternity Pay and 13 weeks unpaid) compared to only two weeks of paid paternity leave available for fathers.

- Shared Parental Leave allows eligible parents to share up to 50 weeks’ leave and 37 weeks’ pay previously only available to the mother but it is rarely taken up because the policy is too complicated, mothers are reluctant to give up part of their entitlement, and it is too low paid (at £148.68 a week or 90% of average weekly earnings if they are lower). In Greater Manchester, men have lower wages than the national average (11.5% less than the median figure for England in 2016) so the even lower pay of Shared Parental Leave will deter Greater Manchester fathers from taking it up.

- Childcare is expensive and costs continue to rise. In the Northwest of England, the average cost of full-time childcare (50 hours per week) for children aged under two was £177.06 in 2015 - equivalent to 38% of average full-time gross weekly earnings in Greater Manchester at that time (the Greater Manchester average full-time weekly wage was £472). This discourages the lower earner (usually the mother) from returning to work after having children because it isn’t financially worthwhile. The statutory early years childcare entitlement provides 30 hours of free childcare a week but only covers 38 weeks of the year for children aged three and four (and some two year olds from disadvantaged backgrounds). Although take-up for 3 and 4 year olds is near universal across the Northwest of England, it will be difficult for many mothers in Greater Manchester to find a job which is compatible with these hours, plus there is a childcare gap between the end of maternity leave and the start of the free provision.

- The ‘Right to Request’ flexible working allows parents to request a change to their hours of work, days of work or place of work to fit in their caring responsibilities. Yet flexible working continues to be more commonly taken up by women, particularly mothers, in the form of part-time work. On top of this, national data shows that men are less likely to make a request for flexible working and are more likely to get their request rejected when they do.

What influences fathers to get involved at home?

Our research using the UK’s Millennium Cohort study shows that if a father shares childcare equally in the first year of parenthood, he is more likely to be involved when the child is aged three.

We also found that fathers were more likely to be involved when the child was aged three if the mother worked full-time, and if the father worked standard rather than long full-time hours (ie 30-40 hours per week as opposed to 48+ hours per week).

So to get fathers more involved in raising their children, it is important to provide the conditions which facilitate work-time adjustments from birth onwards.

What needs to be done?

Well paid paternity and parental leave is pivotal for providing fathers with the opportunity to care for their children during the first year of a child’s life as are flexible working hours, which are more compatible with family life. One way of increasing take up of Shared Parental Leave is through running a campaign to promote it with local employers, and providing better resources for them to use (eg, see Making Room for Dads), as this may help to raise awareness and clarify fathers’ rights.

Making Room For Dads

However, it is important that these provisions are combined with other measures to support maternal employment such as good quality, flexible and affordable childcare. Although the free early years childcare entitlement will benefit some families, childcare provision could be designed in a more targeted and cost effective way across Greater Manchester so as to channel support to those on low wages given the prevalence of households stuck in low paid work.

It is also vital to step up efforts to reduce the gender pay gap. Although the Greater Manchester gender pay gap is lower than the national average, which reflects lower overall wage levels, it still stands at 8.2%, which perpetuates the logic for the father to invest his time in employment, and the mother to leave employment or switch to part-time hours to care for young children.

In their own words:

Women and austerity in Greater Manchester

Anna Sanders

Between 2010/11 and 2017/18, local authorities in England saw a 49% reduction in government funding. According to the Local Government Association, by 2020, councils will have lost 60p for every £1 provided by the government for public services since 2010. Though spending reductions in council budgets have been widespread, they have not been evenly dispersed. In terms of spending power per person, Manchester has been hit the 10th hardest of any council in England.

Reductions in public spending exacerbate gender inequalities. Largely due to lower average incomes and disproportionate caring responsibilities, women are more likely than men to rely on the public sector – through services and transfer payments. They are also more likely to be employed in the public sector, comprising two-thirds of the public sector workforce. Since 2010, it is estimated that women have shouldered 86% of austerity measures.

Between May and December 2017, I conducted six focus groups with women voters across Greater Manchester in order to hear the issues that mattered to them at election time. The focus groups varied in age and location, and were designed to hear from a range of women from different backgrounds.

Lack of access to local, affordable childcare

A key issue that emerged across these groups was women’s concerns relating to reductions in services and local infrastructure upon which they rely. Among these concerns was a lack of access to local, affordable childcare:

“My local Sure Start centre was closed…I relied on it to get the baby weighed, meet the health visitor, the nine month check-up, the two-year check-up, breastfeeding clinics…Even though [my area] has got a lot of people on higher incomes, we still need centres to take the kids to. I have to travel a lot further now.”

“With the expense of it all, it’s whether it’s working for a lot of people, especially if you’ve got multiple children. It’s such a challenge.”

Childcare is equally a men’s issue, but as it stands, women disproportionately undertake the majority of caring responsibilities. More often than not, women are primary carers and secondary earners in the household. As a result, they are often left to ‘fill in the gaps’ when provision is withdrawn. A shortage of accessible childcare facilities creates barriers to women wishing to enter or return to the labour market. This may be of concern particularly in Greater Manchester, where female employment rates are lower than the UK average (68.3% and 70.3%, respectively). Some women mentioned the difficulties they faced in returning to work:

"I probably can’t afford to go back to work full-time, which sounds ironic…by the fourth and fifth day I’ve run out of discounts, I’ve run out of tax credits…I probably can’t afford to go back to work more than three days a week.”

“My husband and I were looking to put our son into nursery for three or four full days a week. If you took away the 15 free hours on top of that, it would still cost several hundred per month - that doesn’t include food, and you still have to provide nappies. I could just stay at home and be a full-time mum and, sure, that’s difficult for me, but it’s the only option.”

Cuts to local transport

As well as childcare, women raised concerns regarding cuts to local transport. Specifically, those who were dependent on public transport cited cuts to local bus routes:

“I can’t get to Manchester Royal Infirmary on one bus. I have to get a tram and a bus and I can’t do it – it’s an hour.”

“I don’t drive…buses are the easiest way I can get into the city centre. The service I usually use has been axed – it’s limited my access in and out of the city.”

According to the Women’s Budget Group, women are more reliant on local transport (and were three times more likely than men to travel by bus in 2017). Reductions in local transport services have implications for those who might experience issues with mobility, such as the elderly, those with disabilities, and those with young children.

Gaps in data at a regional level

Evidence from these focus groups highlights the impact of public spending reductions in the areas of childcare and transport services, but further data and analysis is needed elsewhere. This should explore, among other things, housing, health, education and domestic violence – all areas that affect the daily lives of women.

There is currently a paucity of government data concerning the gendered effects of austerity. Existing analyses have been primarily produced at the national level. Given the variation in local authorities’ budget reductions, a regional approach to assessing gendered austerity is necessary.

In light of this absence in government data, women’s organisations and gender equality advocates have instead produced their own assessments exploring the impact of austerity on women from a regional perspective. Liverpool John Moores University, for instance, explored public sector cuts on women in Liverpool. Additionally, the Women’s Resource Centre examined the impact of spending reductions on voluntary and community women’s services in London. Elsewhere, Coventry Women’s Voices and Warwick University’s Centre for Human Rights in Practice produced its own local case study on the impact of public sector cuts on women in Coventry. These case studies have consistently highlighted reductions in specialist services for black and minority ethnic (BME) women, and emphasise the need for an intersectional approach in impact assessment.

Without robust local data, it is difficult to assess the full extent to which women have been affected by cuts to local services. Monitoring and assessing the provision of services used by women is integral to ensuring women get access to the support they need. Such assessments should consider how inequalities intersect to leave vulnerable groups of women worse off when service provision is withdrawn.

Gender and sexual violence

Dr Cath White, Dr Rabiya Majeed-Ariss and Professor David Gadd

Sexual violence, including rape and sexual assault, can devastate victims: in the short term when, in addition to psychological trauma, some have also to contend with injuries, unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections; and in the longer term, when problems with infertility, sexual dysfunction, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety and depression emerge. In the UK, less than 1 in 6 victims of sexual assault report to the police. Most adult victims are female. Perpetrators are predominantly male. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) estimated that in 2017:

• 20.3% of women and 3.8% of men aged 16-59 had experienced an actual or attempted sexual assault since the age of 16, equivalent to an estimated 3.4 million female victims and 631,000 male victims;

• 3.1% of women and 0.8% of men aged 16-59 had experienced an actual or attempted sexual assault in the previous year.

In focussing on numbers of people - rather than what has happened to them - such statistics understate gender disparities. Earlier sweeps of the British Crime Survey revealed that women who have been recently sexually assaulted suffered on average two incidents in the last year. Female victims are more likely than men to have been repeatedly victimised, often by the same perpetrator and most typically a current or former partner. Men who have been sexually assaulted more than once are more likely to have been abused by separate perpetrators over their lifetimes, with only a third of male rapes perpetrated by current or former partners. The accompanying violence perpetrated against some victims during sexual assaults can be life-threatening. For example, one in five of the adult women who attended Saint Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre (SARC) in Manchester for a Forensic Medical Examination in 2017 following a sexual assault by a partner or ex-partner had also been strangled (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence of non-fatal strangulation in Saint Mary’s SARC cases

Figure 1. Prevalence of non-fatal strangulation in Saint Mary’s SARC cases

Age and ethnicity

It needs to be understood how gender intersects with other social demographic characteristics to compound vulnerabilities and complicate access to services. The media has focussed on women aged 16-25, who are more than twice as likely as women aged 26-59 to have been sexually assaulted in the last year. Such attention has nevertheless encouraged stereotyping. Some government awareness campaigns, for example, have implied that young women who drink alcohol are to blame if they are sexually assaulted (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Home Office, NHS 'Alcohol know your limits' poster, 2006

Figure 2. Home Office, NHS 'Alcohol know your limits' poster, 2006

Such stereotyping also impacts on access to service provision, discouraging victims who have consumed drugs or alcohol from seeking support and promoting the view that older women are rarely raped. Very few women aged 70 or over referred to Saint Mary’s for forensic medical examinations subsequently attended the counselling sessions available there. Indeed, research reveals that among all age groups, victims are much more likely to first disclose being sexually assaulted to a relative, friend or colleague than to the police or other professionals. Around a third of survivors have never told anyone and there are good reasons for thinking that people from minority ethnic groups are ill-served by service providers. The 2011 Census estimated the black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) population of Greater Manchester to be 17%, but in 2017 only 13% per cent of referrals to Saint Mary’s were from BAME groups. In 2018, Saint Mary’s saw only one person who described themselves as Jewish, and no one who identified as Chinese.

As the UK debate around ‘organised’ child sexual abuse has become unduly racialised, insufficient attention has been paid to the vulnerabilities of children. Analysis of data relating to all 986 examinations of children and young people living in the Greater Manchester over a three-year period showed that:

- 86% of the children and young people attending Saint Mary’s following sexual assaults were girls and 14% were boys. Among those aged under 12, however, boys accounted for one-quarter of the total. On average, boys were younger than girls – the median age for boys was 6 years and for girls 13 years;

- children and young people from minority ethnic groups were under-represented in the client population;

- mental health difficulties were frequently reported by service users aged 12-17: 40% reported mental health issues; 35% reported self-harm; and 12% reported suicide attempts prior to their attendance at the SARC.

Mental health, learning difficulties and adverse childhood experiences

Whilst it is estimated that 15.7% of the adult population have a mental health disorder, 69% of adult clients attending Saint Mary's for a forensic medical examination reported long-standing mental health problems predating the recent assault. Having a learning disability also appears to make people more vulnerable to sexual violence. Whilst 2% of the general UK population are reported to have a learning disability, 7.5% of clients at Saint Mary’s SARC have one. Adverse childhood experiences are often connected to both learning difficulties and mental health problems. Over one-quarter of the young people referred to Saint Mary’s SARC are regarded by social services as children in need of protection, suggesting that failures of safeguarding from an early age play a part in many survivors’ vulnerabilities.

The road ahead

The complexity of these intersecting vulnerabilities makes it critical to routinely appraise how accessible services are to survivors. It also, unfortunately, makes it imperative that service providers are honest with those in crisis about how infrequently police investigations deliver ‘justice’. As few as 4% of reported sexual assault cases result in a prosecution and less than three fifths of prosecutions conclude with a conviction. Policymakers must not pretend that improvements in prosecution and convictions rates are imminent, even though they are necessary.

Instead, they must open a public conversation about why most perpetrators are men. This conversation needs to acknowledge that most men do not rape and that most men and boys are appalled by sexual violence. But it needs also to be clear about the degree to which myths about victim precipitation (the idea that how a victim interacts contributes to the crime being committed) enable some men and boys to define what counts as ‘rape’ more narrowly than the law. It must also highlight that a large minority of men remain reckless around issues of consent, oblivious to who can legitimately give it, and misguided about whether it can be assumed without asking.

St Mary's Centre SARC patient journey

Gender and ageing

Professor Debora Price

While there have been very old people throughout recorded history, the last century witnessed great demographic change with the ageing of populations around the world, especially the ageing of the ‘oldest old’. This is of course a triumph for the progress we have made on clean water, global poverty, raising living standards, improved child and maternal mortality and health, and the prevention and treatment of both infectious and chronic disease. People are now much more likely than ever to survive into mid-life, and then increasingly likely to survive into old age. As the focus of policymakers, researchers, communities and families therefore shifts to those in later life, understanding how and why some groups fare better than others across domains has become a critical question for the coming century. This is so not only for those countries and regions who have already aged, like ours, but for those that will age with unprecedented rapidity in coming decades, especially low and middle income countries.

All societies are organised by gender, and gendered inequalities begin early in life. At each turn, those life experiences will then influence what happens later in life. Gender therefore impacts on all domains of wellbeing in later life. While it is true that women tend to be better socially connected than men in old age, in other areas they are disadvantaged. This is principally through women lacking material resources. They are especially disadvantaged in income, wealth, housing and transport, and living with a far greater incidence of disability and ill health than men. For most people, women’s gendered caring roles across the lifecourse structure their whole lives, including their interactions with paid work and family, which in turn impacts markedly on their material circumstances later on. It is also very important to acknowledge that while about 80% of men die married, this is true for only a minority of women, who mostly live on their own towards the end of their lives.

Deceiving statistics

In later life, women have much less state and private pension and are much less likely to be in good quality paid work. Although we have little data on later life, they have poorer housing through the life course and this is therefore unlikely to change in old age. It is often difficult to see women’s poverty in later life because while they are married or cohabiting, and for all official statistics their resources are aggregated with their partners. We observe older women apparently catapulted into poverty by widowhood or divorce, although this really is just a reflection of how low their material resources were within their partnerships. We know from decades of research that financial and material resources are not shared equally within households and that there is often hidden poverty for women behind closed doors. Domestic violence in later life is also a subject that we know very little about. However, even where this is not so and a partnership is a strong and supportive one, when a partner’s resources are lost on widowhood or divorce, this can have severe consequences for women.

The discussion about gender and health is complicated because women in almost all countries of the world have greater life expectancy than men. This is partly believed to be a genetic advantage of some sort, but is also because men have, over the lifecourse, a greater propensity to smoke, undertake risky behaviours, have dangerous jobs and it is men that are required to fight (and die) in wars. These are clear gendered disadvantages for men. We are increasingly realising however that what matters for those who survive into old age is how well you are able to live, free from disability and chronic ill health. Measures have been developed therefore of healthy life expectancy, or disability free life expectancy, and on each of these, women are greatly disadvantaged. Women live with much greater morbidity and disability, for longer, and for a greater proportion of their remaining life after 65.

Inequalities in later life

How gender intersects with other disadvantaged outcomes is a very important question, and one that we know far too little about. We especially need to understand inequalities in later life on lines of gender and ethnicity, gender and social class, and gender and marital history.

We have seen official data move in the opposite direction, with the individual income series discontinued, and important reports like the Pensioners Income Series containing no meaningful analysis of gender. Housing, wealth, illness, disability, food insecurity, cold homes and access to transport are also important measures. We need a full understanding of caring roles, and the impact of these in later life too.

For city-regions, the key to understanding gendered inequalities is to collect data on the items of interest, disaggregate all data by gender, and ensure that all policy analysis is sensitive not only to gender but also interactions with other characteristics of disadvantage in later life.

Policy@Manchester analysis

Policy@Manchester has worked with Professor Francesca Gains to analyse 2019 and 2020 data for the ten combined authorities in England and the ten boroughs within Greater Manchester.

Using Annual Population Survey data and current reporting categories, these graphs show rates of female employment in different sectors, and levels of full-time and part-time work by sex in different occupations.

Click on Figure 1 to explore the interactive graphs (opens new website).

With special thanks to our contributors:

David Gadd is Professor of Criminology at the Centre for Criminology and Criminal Justice in The University of Manchester's School of Social Sciences.

Francesca Gains is Professor of Public Policy and Academic Co-Director of Policy@Manchester at the University of Manchester.

Donna Hall CBE is Chair of the New Local Government Network and Honorary Professor of Politics at The University of Manchester.

Debra Howcraft is Professor of Technology and Organisation in The University of Manchester's Alliance Manchester Business School.

Ruth Lupton is Professor of Education and the Head of the Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit at The University of Manchester.

Dr Rabiya Majeed-Ariss is Research Associate at Saint Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre.

Dr Helen Norman is Research Fellow in Sociology at The University of Manchester.

Debora Price is Professor of Social Gerontology and Director of the Manchester Institute for Collaborative Research on Ageing (MICRA) at The University of Manchester.

Jill Rubery is a professor in the Alliance Manchester Business School and Director of the Work and Equalities Institute.

Anna Sanders is a Doctoral Researcher in Politics in the School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Nina Teasdale is a Fellow at the Centre for Economic Justice, WiSE, Glasgow Caledonian University.

Dr Catherine White is Clinical Director of Saint Mary’s Sexual Assault Referral Centre

This publication is based on a meeting paper that Professor Francesca Gains brought together for the Greater Manchester Women's Voices Task and Finish Group in June 2019. The meeting paper provided an evidence base for the group to use to form its action plan. The articles in this publication discuss both national and regional policy and provide information that can be used to inspire policy nationally and in other city regions.

Image in the Striving for gender balance in the IT industry article by Professor Debra Howcroft is courtesy of Bletchley Park Trust.

policy@manchester.ac.uk

@UoMPolicy

#OnGender

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the respective authors and do not represent the views of The University of Manchester.

July 2019

The University of Manchester

Oxford Road, Manchester

M13 9PL

www.manchester.ac.uk