Power in Place

Evidence-led solutions for thriving and sustainable communities

Foreword

The evidence set out in last year’s Levelling Up White Paper gave official recognition by the government to the deep-rooted and long-standing nature of regional inequalities across the UK. The White Paper endorsed the earlier findings in the report Make No Little Plans, published in 2020 by the UK2070 Commission, which I chair. Those people who questioned the scale and depth of inequalities have been exposed as modern ‘flat earthers’.

Political rhetoric now needs to be translated into policies and programmes of action on the scale and with the urgency needed to meet these challenges. This is still missing. In part this is because of the complexity of the challenge and the need for change in both our institutional structures and technical capacities.

This is highlighted in the diversity of contributions in this Policy@Manchester publication. It illustrates the range of policy fields and policy interventions that need to be brought to bear, ranging from tackling poverty, preventing ill-health, and the importance of reskilling and green spaces. On top of this, policy interventions are required to tackle inequalities in higher education, transport, energy, housing conditions, and employment.

There are therefore no silver bullets; there needs to be a fusillade of assault on the problem across this whole spectrum of needs and on many fronts. There is however an ‘elephant in the room’ that impedes real progress, namely, the lack of a truly place-based approach to policy. As expressed in this report, we need to visually see the differences in different areas of the country. This apparent tautology is at the heart of the problem. Despite the rhetoric of levelling up places, government policies are still ‘place blind’.

This paradox arises because policies and programmes to address regional inequalities are fragmented in three critical ways. Firstly, geographical administrative boundaries are unrelated to, and fragment, the areas within which people search for jobs, housing, and social activity. Therefore, areas used for policymaking and implementation have no coherence or consistency. This problem will persist until there are effective institutional arrangements for cross-boundary strategic planning.

Secondly, the functions of government are fragmented into departmental silos, with limited coordination. This has been highlighted in the recent policy on Powering Up Britain to enhance energy security and seize the economic opportunities to deliver on our net zero commitments. It, however, makes no reference to levelling up nor the need for a just transition. There is therefore the risk of conflicting action between creating a green economy and rebalancing the economic geography to redress the spatial inequalities.

Thirdly, the time horizons used in policies are fragmented as a consequence of the above. There are no common time frames for policies or areas. This is reinforced by Green Book short-term accounting rules which effectively write off long-term goals for the environment. The result of this fragmented governance environment is that policy operates in a place-less environment. Decisions about the future of most parts of England are taken without any plan for their future – without any lens in which to see clearly what is happening or proposed.

A place-based approach requires us to move away from being the most centralised nation in the developed world. This task is too important and complex to leave to government alone. Not only must local government be re-empowered and a parity of esteem between central and local government be established, but also civil society needs to be enabled, resourced and engaged in the endeavour of rebalancing the nation. The articles in this report provide evidence-led ideas about how we can improve place-based approaches to tackle inequalities. We need to re-assert the critical role of communities – the place that people identify with, the place that defines their identity, and the places with which they are interdependent.

Lord Bob Kerslake

Chair of the UK2070 Commission

Making the local matter

How the forces of power, poverty and place shape schools and schooling

Dr Carl Emery and Louisa Dawes

In 2020/21, 3.9 million children in the UK were living in relative poverty (in households with an income less than 60% of the median household income). While policy aims to address the attainment gap linked to poverty, the current approach will take 500 years to close that gap. What needs to change to move children out of poverty quickly and equitably?

While policy aims to address the attainment gap linked to poverty, the current approach will take 500 years to close that gap.

Poverty is complex

Poverty is not ‘one-size-fits-all’. Family composition, ethnicity, age, disability and place significantly contribute to likelihood and experience of poverty. A lone-parent of Pakistani origin in a Rochdale housing association flat will experience poverty differently to a White British two-parent family in a private rented house in Southampton. Moreover, when we factor in the ‘poverty premium’, the additional costs low-income households pay for essential services and goods, it becomes evident that poverty is nuanced, fluid and place shaped.

How does poverty impact children?

Despite decades of policy attention, the attainment gap (the difference in educational performance between pupils eligible for free school meals (FSM) and their peers) at GCSE has barely changed, and at all stages of children’s education attainment inequalities persist. Although the total share of pupils achieving ‘good’ GCSEs (Grade C or Grade 4) has increased, children from better off families have been 27-28% more likely to meet these grades throughout the last 15 years.

Data shows that children leaving school with few or no meaningful qualifications are less likely to enter into, and progress in, employment; to support the learning of their own children; or to achieve social mobility goals. Negative educational experiences also have a detrimental effect on communities, shaping environmental, social, economic and democratic engagement.

Beyond attainment, poverty has broader impacts on children’s social and emotional skills, mental health, behaviour, and wider wellbeing. Put simply: poverty makes school and schooling harder for all involved.

The current response to child poverty

For the past decade, policy discourse around child poverty and education has centred on raising standards of teaching and learning so that schools can ‘do it alone’. Education policy reform has adopted a telescopic focus on narrowing the attainment gap to achieve social mobility. While educational achievement is important, it is not the panacea for child poverty. Improving educational achievement among disadvantaged pupils has not reduced child poverty, and calculations estimate that it will take 500 years to close the attainment gap.

Current practice takes little account of individual characteristics such as gender, race and class. Policy initiatives in education advocate ‘off the shelf ’ practices driven by big data, which focus on ‘improving’ teaching through prescribed pedagogies and ‘extended’ learning or wellbeing programmes. The same interventions are delivered throughout the UK. Many of these activities are funded through the Pupil Premium (PP) initiative, a per pupil grant, generally for pupils receiving FSM, to reduce the attainment gap. Herein lies a critical problem – the attainment gap approach only understands poverty through progress measures, meaning that children are reduced to standardised metrics that ignore the fluid and contextually distinct nature of poverty.

Children are reduced to standardised metrics that ignore the fluid and contextually distinct nature of poverty.

Local Matters: A place-based approach to child poverty

Our research programme, Local Matters, is premised on the belief that this standardised approach, that obscures structural, social and employment factors and conceals the history, culture, geography and psychology of the place children live in, is inadequate.

Local Matters is a place-based, relational, socio-economic approach to child poverty. We are supported by diverse groups of professionals and agencies, who acknowledge that schools need to utilise local, contextualised knowledge alongside place-based evidence to enhance their practice. We champion a need to develop a deeper understanding of the local by exploring the values, power and positions of those living together in communities and hearing the voices of all parties, including pupils, teachers, parents and local policy actors.

“You need to understand how poverty looks in your area and how certain actions and school decisions can put pressure on parents and children to live up to the expectations of others. By having a deeper understanding, through Local Matters, of the impact of the choices we make, about the financial decisions that require parents to participate, (for example, dressing up on World Book Day) we will help to eliminate further barriers to learning.”

Primary School Headteacher

Local Matters supports practitioners across the education spectrum to collaborate on building research- driven, sophisticated accounts of disadvantage. These accounts are drawn from locally lived experiences, show structural inequalities, and support teachers in building a place-based critical response to poverty. Our programme equips participants with social research skills, enabling them to become locally embedded social justice researchers. This expertise on the local poverty context is applied, through action research, to school practice and policy. Local Matters brings the school community together and gives a voice to all, linking ‘what works’ with ‘what matters’.

The role of policy

Our experiences of working with a range of policy actors over the past five years have shown that there is a need to go beyond current, limited data to gather thick, intelligent data on the lived experiences of those most impacted by poverty. It is vital that decision-makers step into the local community, put feet on the ground, and listen carefully to a range of voices that represent all people, not just those who are most visible or speak loudest.

Secondly, there is a need for policymakers to move away from imposing traditional, top-down models onto communities. Instead, policymakers must build recognition, that is respecting and reflecting back the full range of identities and cultural differences in the community, through asking what parental engagement and attainment mean to parents and pupils across different contexts.

Policy must redistribute time, money, access, power and activities based on real need rather than myths or big datasets.

Finally, policy must redistribute time, money, access, power and activities based on real need rather than myths or big data sets. We encourage policymakers to seek out and create safe spaces for families and children living in poverty to relate their experiences rather than fitting into ascribed one-size-fits-all roles.

In a fragmented education system with largely homogenised curricula and a standardised inspection regime, we call specifically on multi academy trusts to recognise the complexities and necessity of local context. Schools need greater autonomy in the design of their curricula, but within a locally federated system, and must be granted the ability to judge and enact ‘what matters’ with ‘what works’ locally.

About the authors

Dr Carl Emery is a Lecturer in Education and co-leader of the Power, Inequality and Activism Research Group at the Manchester Institute of Education in The University of Manchester.

Louisa Dawes is a Senior Lecturer in Education and joint convener of the Teacher Education and Professional Learning (TEPL) Research Group at the Manchester Institute of Education in The University of Manchester.

Strengthening participation in devolved policymaking

Designing democratic innovation to tackle inequalities

Professor Francesca Gains and Professor Liz Richardson

Developments in local governance and devolution over the past decade have provided new opportunities to tackle policy problems from a place-based angle. Innovations to strengthen participation can ensure more people participate in policymaking to help mitigate issues such as structural inequalities which affect them first hand.

Representative democracy

Place-based policymaking is based on the longstanding principles and statutes governing representative democracy. Citizens (those registered to vote) elect local councillors, and the largest party in a ‘place’ takes control of the council and sets the policy framework. Voters use parties to help choose between policy stances to reflect their own political preferences. And the way representatives decide how to spend public money, what to spend it on, and then account for their choices is tightly controlled by systems of accountancy and accountability.

But there are many reasons why local government has long sought to strengthen wider participation in policymaking alongside formal representative politics. Some under-represented and marginalised voices may not get heard in electoral processes, for example those who are not registered to vote, or who do not have a settled address. Even if electoral systems work as well as they can, there is an ‘in-built’ problem of minority voices being overlooked. Councillors represent the majority, and this gives a simple, clear, and overall fair way to decide. But a majority system can also have downsides; for example, if sections of the community are in a minority, they may sometimes lose out unfairly in decisions.

The role of local governance in strengthening participation

The development of successful and effective policies to tackle deep-rooted policy problems such as inequalities is vastly improved through the co-production of policies. This includes working with those who have first-hand experience and knowledge of problems, alongside the expertise of local councillors, researchers, council officers and other civic leaders. However, there is unfulfilled potential to use more participatory methods more often in local governance.

With the rapidly developing map of English devolution there is huge potential to take a place-based approach to tackling inequalities.

We have seen space for these opportunities in newer forms of sub-national governance, such as mayoral combined authorities. The devolved powers and budgets of combined authorities are well placed to tackle place-based inequalities around education outcomes, skills development, employment and health outcomes. With the rapidly developing map of English devolution there is huge potential to take a place- based approach to tackling inequalities, if meaningful participation of under-represented groups can go hand in hand with the requirements for public probity around public funds.

Greater 'people power'

The untapped potential for more participation to help tackle inequalities is a key focus in Greater Manchester following the Independent Inequalities Commission review, which argued for greater ‘people power’. Greater Manchester had already brought forward some democratic innovations in the region, including the establishment of panels covering all strands of inequalities. Earlier research examining the introduction of city mayors and directly elected police and crime commissioners suggests the mandate underpinning directly elected place-based leaders can encourage democratic innovation.

The untapped potential for more participation to help tackle inequalities is a key focus in Greater Manchester.

Following a roundtable set up by Policy@Manchester to bring together researchers, campaigners and policymakers to examine people power, we were invited to work with Greater Manchester policymakers in an action research project

The three aims of the project were to establish design principles to underpin governance processes for developing people power; audit and capture what participatory policymaking is taking place across the ten boroughs; and make recommendations to strengthen the linkage between participatory ‘people power’ and formal statutory governance processes.

Design principles

After reviewing the existing research, we argued that to tackle weaknesses, local participatory decision- making should be underpinned by certain design principles. Membership of decision-making forums should be open, porous, transparent and representative of the communities served. The voices of under- represented groups should be embedded in decision-making, which will avoid tokenism and a lack of representation, and ensure that their input is routinised and responded to. And all types of expertise and evidence should be valued and examined, from the expertise reflected by the gathering of evidence by policymakers and researchers alongside the lived expertise of those with experience of the policy problem.

Examples of best practice

We then shared and discussed these principles at a workshop on strengthening participation across Greater Manchester, which brought together members from the equalities panels and councillors across all the boroughs, including those with equality, diversity, inclusion, and consultation portfolios. We heard from international experts around the best practice for participatory budgeting, running citizens’ panels, and co-production.

This built a ‘menu’ of different types of participatory policymaking and when and why they might be used. Participants in the room shared examples of existing ways in which people power was being used across the boroughs, and the workshop finished with the aim of supporting the development of a community of practice for all involved – elected councillors, researchers, members of the equality panels, and officers from the combined authority and the boroughs.

Strenghtening participation in policymaking to tackle education, skills, employment, and health will ensure that 'levelling up' funding and policies are well targeted, effective and inclusive.

Key recommendations

The possibility for strengthening participation in policymaking to tackle inequalities is considerable, as more and more mayoral combined authorities are created. Strengthening participation in policymaking to tackle education, skills, employment, and health will ensure that Levelling Up funding and policies are well targeted, effective and inclusive. Our key recommendations to achieve this are below.

Firstly, participation should be underpinned by a set of key design principles for decision-making. The processes of participation should be open and porous, as well as transparent, inclusive, embedded, and valuing the fullest range of expertise.

Secondly, the extension of people power can complement representative democracy and enhance decision- making if it is routinely connected to policy development, scrutiny functions, and the work of local elected members.

Finally, when considering how to strengthen participation, consider the target audience, objectives, and all the methods available, and choose wisely.

About the authors

Professor Francesca Gains is a Professor of Public Policy at The University of Manchester.

Professor Liz Richardson is a Professor of Public Administration at The University of Manchester.

A place to #BeeWell

Neighbourhood effects on young people's wellbeing

Professor Neil Humphrey

There is a public health crisis in young people’s wellbeing. Approximately one in six young people experience high levels of emotional difficulties that are likely to warrant significant additional support. A number of factors can impact wellbeing, and the neighbourhood in which a young person lives is one of them, with differences seen across Greater Manchester. So, what is needed to support young people in neighbourhoods with lower levels of wellbeing?

#BeeWell

To ‘be well’ includes having a sense of meaning, purpose and control, as well as feeling satisfied with life, understanding and valuing yourself, and feeling good (experiencing positive emotions). Recent research indicates that many young people don’t currently feel this way.

The aim of #BeeWell is to make young people's wellbeing everyone's business

#BeeWell is an innovative programme that blends academic research and youth-led change to ‘pivot the system’ and address this major societal problem. The aim of #BeeWell is to make young people’s wellbeing everyone’s business.

As part of the programme, data on the domains and drivers of young people’s wellbeing are collected on an annual basis, with insights and recommendations fed back to schools, local authorities, communities and a coalition of over 100 project partners.

The findings are shown via interactive data dashboards and themed analyses, and are underpinned by support from our partners at the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families, providing an evidence base to inform decision-making across the system.

Can wellbeing be attributed to place?

Currently, we know far less about the effects of place on young people’s wellbeing, in contrast with other developmental contexts such as family and school. Our team have begun to explore the role of neighbourhoods and how this can impact young people’s wellbeing, as another step towards solving this crisis.

The first wave of #BeeWell survey data included approximately 38,000 young people aged 12-15, and linked socio-demographic data (for example, special educational needs and ethnicity) and neighbourhood data (such as access to health services, proximity of charities, and levels of crime). Through two studies, we examined how much of the variation in young people’s wellbeing can be attributed to differences between the neighbourhoods in which they live.

We also examined whether inequalities in wellbeing between different socio-demographic groups vary across neighbourhoods, and which neighbourhood characteristics are associated with individual wellbeing outcomes. We made sure to check whether the different geographic units used to define neighbourhood boundaries made any difference to their influence on wellbeing.

Studying neighbourhood influences

The first study focused on neighbourhood influences on young people’s life satisfaction and emotional difficulties, such as feelings of sadness and anxiety. We split Greater Manchester into 300 locales and linked data on neighbourhood characteristics from the Co-Op Community Wellbeing Index and the #BeeWell Survey. The Community Wellbeing Index spans a variety of characteristics including, for example, education and learning, health, and relationships and trust. In the #BeeWell survey we ask young people about their local area, including, for example, how safe they feel and whether there are good places to spend free time.

The second study focused on neighbourhood influences on young people’s loneliness, and used a smaller geographic unit, local super output area (LSOA), of which there are approximately 1700 across Greater Manchester. It linked data on neighbourhood characteristics from the Indices of Deprivation (which spans a range of indicators including health, crime, and the living environment) with population density and the same #BeeWell survey data as in the first study.

How neighbourhood differences affect wellbeing

The research showed that neighbourhood characteristics are significantly associated with different domains of wellbeing. As expected, effects were slightly more visible in the smaller geographic units that likely better reflect how young people think about the boundaries of their neighbourhood.

Neighbourhood characteristics are significantly associated with different domains of wellbeing.

Our analyses also showed that inequalities in wellbeing between different social groups varied across neighbourhoods. For example, disparities in loneliness between LGBTQ+ young people and their peers differed based on the neighbourhood in which they resided.

Another theme that was evident across the research was the influence of social cohesion and relational characteristics of neighbourhoods. Young people feeling safe in their local area and feeling that there was support for wellbeing among local people were among the strongest predictors of wellbeing. Whether local people could be trusted, whether neighbours were helpful, and whether there were good places to spend their free time in their neighbourhood, were also positively associated with their wellbeing.

In addition to the above, life satisfaction was higher and emotional difficulties were lower in neighbourhoods with better access to health services and lower GP antidepressant prescription rates. Furthermore, life satisfaction was higher in neighbourhoods with lower unemployment and free school meal eligibility rates. Loneliness was higher in neighbourhoods with higher skills deprivation among children and young people, higher geographical barriers (for example, longer distance to places like schools, shops and doctors’ surgeries), and lower population density.

Making places work for wellbeing

Our findings provide evidence that place is a contributory factor for young people’s wellbeing. It speaks directly to the Levelling Up agenda and highlights the persistence of inequalities at the neighbourhood level.

Evidence that wellbeing disadvantage among minority groups may be affected by their neighbourhood provokes a call for more nuanced responses that identify the locales with increased vulnerability and inequality. Neighbourhood data and profiles are available in our online dashboard to help policy actors identify relevant characteristics in a local area and inform their responses.

We must emphasise and promote a sense of belonging to the local community.

Targeted, hyper-local responses in these areas are as important, if not more so, than national initiatives. They are better placed to respond to the complex contextual factors that underpin and reinforce wellbeing inequalities.

Our analyses of the influence of different neighbourhood characteristics suggest that in order to improve wellbeing among young people, we must emphasise and promote a sense of belonging to the local community, as well as improving social cohesion, integration and inclusivity, and building opportunities and structures for social support.

About the author

Professor Neil Humphrey is a Professor of Psychology of Education in the Manchester Institute of Education, The University of Manchester, and is the academic lead for the #BeeWell programme.

Holding up a mirror

Reflections on making local environmental policy more inclusive

Professor Sherilyn MacGregor and Dr Udeni Salmon

Behaviour change is central to discussions about achieving net zero and encouraging more sustainable practices. But there are limits to focusing on individual behaviour change with a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach in a policy field that lacks understanding of cultural diversity. So how can environmental policy take a place-based approach that ensures it works for all communities within an area? And what needs to change to move away from views that some people are ‘hard to reach’?

Assumptions about behaviour

Awaab Ishak was two years old when he died from exposure to mould in a Rochdale flat. At the inquest, the landlord admitted that they did not act because they blamed the mould problem on the cooking and bathing practices of Awaab’s Sudanese parents: “We did make assumptions about lifestyle and we accept that we got that wrong”. The child’s father called out these assumptions as racist, an assessment that casts light on what happens when a focus on individual behaviour obscures the structural causes of social inequality. It is a powerful reminder that human behaviour is complex and making assumptions is dangerous. That is why it is essential that decision-makers take cultural differences, as well as institutional racism, seriously.

Researching with Global South immigrant communities in Manchester

There is growing awareness within environmental politics research that greater attention to inequality within wealthy countries like the UK is needed to develop inclusive policies for a just transition to a sustainable society. Negotiations at the COPs, and most media coverage, show that inequalities exist between rich and poor countries and must be redressed on a global scale. However, there is rarely parallel discussion of the experiences of people living in the Global North who have migrated from the Global South (the ‘south within the north’ as it were). Such populations hold first-hand knowledge of extreme climate breakdown yet have often had lifestyles that contributed little to the problem.

This analysis informs the Towards Inclusive Environmental Sustainability (TIES) research project, which is gathering data on the household practices and environmental perceptions of people who have migrated to Manchester from countries of the Global South. Working with Somali and Pakistani residents, we have conducted a survey and interviews that give us insights into participants’ experiences of living in, and leaving, severely climate challenged homelands. The majority of our participants live in underserved wards in south-central Manchester, where the quality of the local environment and housing is low compared to affluent areas of the city.

We have learned from them that most immigrants from Somalia and Pakistan are just as concerned about climate change as UK born citizens, that they engage in a wide range of ‘green’ practices (such as recycling and energy saving), that their religious beliefs provide strong motivation for conservation, and that many are upset by what they see as the effects of a wasteful, throw-away culture in the UK.

Lack of diversity in the environmental sector

Our research has also gathered evidence that policymakers in Manchester are aware of – but uncertain how to address – the lack of diversity within environmental politics in the city. A 2022 study found that under 5% of people working in UK environmental professions identify as a racialised minority. That means most of the people making policy on net zero (and environmental policy more broadly) come from a narrow range of backgrounds and probably have few opportunities to reflect on how this shapes policymaking. Arguably, when behavioural sciences are favoured over social sciences in the development of environmental policy, there is room for assumptions to be made about people’s lives that don’t get challenged by evidence, let alone by the voices of marginalised people.

Most of the people making policy on net zero (and environmental policy more broadly) come from a narrow range of backgrounds and probably have few opportunities to reflect on how this shapes policymaking.

Challenging assumptions, enabling inclusivity

In 2019, our team published a report on findings of a pilot study based in one of the most diverse wards in Manchester that sets out recommendations for how to challenge assumptions and enable greater inclusivity in local environmental governance. The following are three recommendations that have been further developed by the TIES research.

A place-based approach, where conversations are held in neighbourhoods and households, enables better understanding of people's everyday lives.

First, we recommend questioning the assumptions underpinning behaviour-change focused policy, specifically that all individuals are equally able and responsible to change what, how and how much they consume. A place-based approach, where conversations are held in neighbourhoods and households, enables better understanding of people’s everyday lives and resists top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions. Observing how people live and listening to what they already know are important methods for challenging the view that people require education and nudges in order to behave in pro-environmental ways. Many daily practices ‘imported’ from Global South contexts already have low environmental impact.

Second, there is a need for intersectional analysis of power relations that shape household consumption practices. Intersectionality, a concept that describes how systems of inequality (for example, class, gender, and race/ethnicity) intersect to create unique dynamics and effects, is gaining ground within environmental and climate policy. The 2021 report of the Cambridge Sustainability Commission on Scaling Behaviour Change stresses that policymakers need to think more deeply about how the interplay between social and political identities affects climate injustice. When such analyses are advocated by mainstream social scientists, the time has come for the mainstreaming of intersectionality into UK environmental policy.

Reflecting on - and changing - professional practice

Our project seeks to avoid ‘othering’ people from Global South immigrant communities by focusing exclusively on their stories. We are researching with them to help combat this possibility, but nevertheless some express suspicion: ‘why us?’. In response, we stress that at the same time as asking questions about their everyday household practices we are ‘holding up a mirror’ to people in power. We call this a symmetrical approach to researching local governance.

A third recommendation, then, is that all those in positions to design strategies, make decisions and set behaviour change targets for the whole population must practice symmetry and reflexivity. So, rather than positioning minoritised people as ‘others’ with deficiencies in language, cultural know-how, or motivation, and therefore in need of special campaigns to tell them how to behave, reflexivity involves looking at the deficiencies, assumptions and privilege that sustain both institutionalised whiteness and racism. In effect it flips the script so that rather than assuming some groups are ‘hard to reach’ the question becomes why are ‘they’ so easy to blame?

About the authors

Professor Sherilyn MacGregor is Professor of Environmental Politics in the Sustainable Consumption Institute, The University of Manchester, and leads the Leverhulme Trust funded project Towards Inclusive Environmental Sustainability (TIES).

Dr Udeni Salmon is a Research Associate in the Sustainable Consumption Institute at The University of Manchester, researching migration, intersectionality and family business.

Ill-health and deprivation

How can we address health inequalities in left behind neighbourhoods

Dr Luke Munford

We have long known that the health of people living in deprived areas is worse than the national average. But this raises important questions, such as how big is the gap? Is it narrowing or growing over time? Are some deprived places worse off than others? And how do health inequalities affect economic performance?

Investigating outcomes in left behind neighbourhoods

To answer these questions, we were commissioned by the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Left Behind Neighbourhoods to investigate health and economic outcomes in ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods.

We examined health outcomes and inequalities in the 225 left behind neighbourhoods and the rest of England, and the long-term effects of health inequalities on individuals and the economy.

Of the 225 left behind neighbourhoods (LBNs) nationally, 138 are in the North of England (61%), 54 are in the North West (24%), and 17 are in Greater Manchester (8%).

What is a left behind neighbourhood?

We defined left behind neighbourhoods (LBNs) as areas that were in the most deprived 10% of areas according to the 2019 Index of Multiple Deprivation and in the 10% of areas of greatest need in the Community Needs Index. The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) is a composite measure, developed by the ONS, of the relative deprivation of areas in terms of seven key domains. The Community Needs Index (CNI) was developed by Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion to measure how an area performs in terms of social infrastructure.

We identified 225 neighbourhoods as being left behind, and they were typically found in post-industrial areas in the Midlands and North of England, as well as coastal areas in the South East.

Of the 225 LBNs nationally, 138 are in the North of England (61%), 54 are in the North West (24%), and 17 are in Greater Manchester (8%).

We also looked at what we called ‘other deprived areas’ – areas that rank in the most deprived 10% in the 2019 IMD, but are not in the 10% of areas of highest need according to the CNI. We compared a range of health and economic outcomes in LBNs and other deprived areas to the English average.

Health inequalities in England

In LBNs, men live 3.7 years fewer than average and women 3 years fewer. Both men and women in these LBNs can expect to live 7.5 fewer years in good health than their counterparts in the rest of England. Worryingly, there is evidence that this gap in life expectancy has been growing since 2010. Health inequalities have been widening not narrowing.

Both men and women in these LBNs can expect to live 7.5 fewer years in good health than their counterparts in the rest of England.

There is a higher prevalence of 15 of the most common 21 health conditions compared to other deprived areas and England as a whole. These health conditions include high blood pressure, obesity and chronic lung conditions (such as COPD). In addition, people in LBNs claim almost double the amount of incapacity benefits due to mental health related conditions compared to England as a whole.

During the earlier parts of the COVID-19 pandemic, people living in LBNs were 46% more likely to die from COVID-19 than those in the rest of England.

Impact on the economy

People living in LBNs had it worse before the pandemic, were more affected by the pandemic, and will be harder hit by the current cost- of-living crisis. In the current financial and economic climate, more and more people are facing unexpected financial hardships or being pushed further into poverty, particularly in LBNs.

Tackling these health disparities will not only improve the lives of millions of citizens, it will also bring significant savings to the taxpayer. If the health outcomes in local authorities that contain LBNs were brought up to the same level as in the rest of the country, an extra £29.8bn could be put into the country’s economy.

If the health outcomes in local authorities that contain LBNs were brought up to the same level as in the rest of the country, an extra £29.8bn could be put into the country's economy.

Tackling health disparities

To address health inequalities, the government’s national Levelling Up strategy must include a strand on reducing spatial health disparities through targeting multiple neighbourhood, community and healthcare factors. The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities is an opportunity to catalyse action for population health.

To address health inequalities, the government's national 'levelling up' strategy must include a strand on reducing spatial health disparities through targeting multiple neighbourhood, community and healthcare factors.

Long-term ring-fenced funding is needed to ensure more effective delivery of resources on the ground, and for targeted health inequalities programmes (drawing on initiatives such as Healthy New Towns) with a hyper-local focus that prioritises those left behind areas with the worst health outcomes that have been most affected by COVID-19.

Consistent and long-term (10-15 years) financial support is needed to build local social infrastructure in left behind communities that lack the community capacity, civic assets and social capital needed to support and benefit from preventative and neighbourhood-based health initiatives. This is key to improving local outcomes, and it could be achieved through mechanisms such as the Community Wealth Fund, which would give local residents the means to develop those services and facilities that best meet their needs.

Community public health budgets should be safeguarded so that action to relieve acute NHS backlogs does not undermine efforts to tackle the root causes of ill-health and boost health resilience in deprived and left behind communities.

Government and local authorities should prioritise left behind neighbourhoods for investment in new Family Hubs to help improve wellbeing and local life chances. Existing services should be redesigned to respond to the specific challenges within a local area. Local health initiatives that increase the level of control local people have over their life circumstances should be prioritised, from community piggy bank and community health champions initiatives, to more structured forms of community governance and decision-making.

About the author

Dr Luke Munford is a Senior Lecturer in Health Economics at The University of Manchester and researches the causes and consequences of health inequalities.

Urban regeneration policymaking

Building wellbeing into place-based urban regeneration policymaking

Dr Jamie Anderson, Dr Joanna Barrow, Dr Arbaz Kapadi and Professor James Evans

Urban regeneration schemes are happening across the UK. Place-based policymaking for urban regeneration is crucial when addressing long-term population health and wellbeing. It can also improve the resilience of communities to environmental stressors (such as climate change), socio-economic shocks (such as cost-of-living), and the uneven distribution of negative impact. However, evidence about the impacts of urban development schemes is lacking, as are tools with which to monitor them.

From 'ill-being' to wellbeing

One way to measure and monitor the economic, environmental and social impacts of regeneration schemes is to develop an outcome impact framework. However, very few robust impact frameworks are used within urban regeneration programmes, and there are issues with those that do exist. Firstly, most monitoring frameworks do not balance objective and subjective measurements. For example, area safety can be low in regard to crime statistics but the same community may not feel safe. Secondly, existing frameworks adopt a pathogenic approach that focuses on the amelioration of disease and disorder.

Wellbeing requires a salutogenic approach that focuses on realising human potential. In short, we need to prioritise wellbeing, not just ‘ill-being’. Finally, wellbeing is a multi-faceted concept. Rather than being imposed from the top down, it requires input from local communities about what to measure and how.

Wellbeing is a multi-faceted concept. Rather than being imposed from the top down, it requires input from local communities about what to measure and how.

Co-designing urban regeneration

We have been working collaboratively with partners in Manchester to create a framework to monitor the economic, environmental and social impacts of regeneration schemes to understand how they can improve wellbeing. This work began when we tracked the impact of the final phase of a ten-year housing- led regeneration program in a highly deprived, post-industrial area on the edge of Manchester city centre that is also at high risk of flooding. While the scheme had delivered new and improved mixed-tenure housing, the area suffered from poor-quality outdoor spaces including a run-down park and unattractive green spaces.

Co-design was a key part of this work. The local community were involved in co-designing a new park, implementing solutions ranging from rain gardens to absorb water, play equipment for children, biodiverse planting, and an index to evaluate the impact of the park on wellbeing outcomes. This involved a partnership approach to understand, in the community’s own terms, what ‘health’ and ‘wellbeing’ meant to them and what changes they would like to see to local outdoor spaces.

Measuring the impact of outdoor spaces on wellbeing

Using a combination of research methods, we created a baseline measure of wellbeing, looking at both this area before the park was built and comparison areas that had similar characteristics but no improvements to their outdoor space. We created a new inclusive measure of social wellbeing called Neighbourhood flOURISHing (NOURISH). This was used alongside a second measure of activities closely associated with wellbeing: socialising with others, physical activity and taking notice of the immediate environment.

We found that wellbeing activities in this area increased substantially over time, once the new park was completed. These changes were apparent three and 15 months after its completion, suggesting that changes to wellbeing and associated behaviours were not a novelty effect. The intervention’s success has inspired further interventions in other similarly deprived and flood-risk areas of Greater Manchester.

The project also highlighted the fundamental value of working with the community and the need to collect social wellbeing data, to provide a snapshot of the salutogenic benefits in motion, and not solely the reduction of risk factors - such as flash-flooding.

Change at a larger scale

We are now putting these lessons into practice at a larger scale for another regeneration project in Manchester that will be completed in the next 10-15 years. Despite a growing economy, overall Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) show North Manchester, where this regeneration project is situated, to be among the 5% most deprived areas in England. This large-scale £6bn urban regeneration scheme is a critical lever to ‘level up’ groups who live with multiple social, spatial and environmental challenges.

Despite a growing economy, overall Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) shows North Manchester, where this regeneration project is situated, to be among the 5% most deprived areas in England.

Again, we are taking a partnership approach, with Manchester City Council, the developer, the local NHS health trust, civic society, and voluntary organisations. Those involved wish to measure the success of the planned regeneration at key stages of the 15-year programme. They hope to involve the collection and use of routine and bespoke data from young people, adults and older people as part of a ‘flourishing index’.

The index, a co-produced ‘theory of change’, and existing data will inform decision-making by providing an understanding of local issues from multiple perspectives and will help encourage working across organisational boundaries.

Long-term place-based monitoring

Scaling up place-based policymaking for urban wellbeing will require considerable resources in terms of financial support and citizen engagement, but the impact of this approach will deliver on value and values. On the one hand, public and private investors are more likely to achieve stronger return on investment, as stronger policies lead to better places and in turn more consistent profit generation. At the same time, public investors are likely to see greater value as NHS burden and anti-social behaviour is decreased. On the other hand, it is an opportunity to do more good and deliver places that take full responsibility for what most communities, irrespective of utilitarian benefits, treasure most highly: experienced wellbeing.

This will require longer timescales and greater ambition. Many regeneration schemes offer an opportunity to mainstream more effective approaches to working with communities and evaluating changes to health and wellbeing, many of which only appear over years and decades rather than weeks and months.

We recommend not limiting data to official ONS or OECD frameworks but also listening closely to local communities and stakeholders.

In order for this approach to work, local authorities, investors and developers must embed long-term relationship building with local communities, researchers, and organisations, such as healthcare trusts and the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector. Partnerships and the insights needed to guarantee long-term wellbeing impacts do not happen overnight. Listen to people’s subjective (self- reported) wellbeing throughout the development project, and it is important to build in flexibility to adapt the project to sometimes dynamic need and what doesn’t work.

Whilst standardisation is helpful, wellbeing is multi-faceted and context specific. We recommend not limiting data to official ONS or OECD frameworks but also listening closely to local communities and stakeholders, drawing on a combination of routinely collected data and bespoke local data. Automated approaches for tailored data collection are increasingly reliable and therefore present promising new opportunities.

About the authors

Dr Jamie Anderson is a Research Fellow in Geography at The University of Manchester, where he leads wellbeing evaluations of prospective urban changes.

Dr Joanna Barrow is a Research Associate in the Department of Geography and Manchester Institute of Education at The University of Manchester, working on research to define, capture and assess social impact primarily in urban contexts.

Dr Arbaz Kapadi is a Research Associate in the Division of Psychology & Mental Health at The University of Manchester, working on implementation science research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). He recently completed his PhD which explored community engagement in the co-production of healthcare services.

Professor James Evans is a Professor of Geography at The University of Manchester, where he directs the Manchester Urban Institute.

Re-skilling places

A new approach for reducing regional inequalities

Dr Eric Lybeck

Current models of education and social mobility take an individualist approach that encourages young people from rural areas and small towns to move to city centres to obtain qualifications and skills. But this approach worsens regional inequalities, as places outside urban centres are left behind. So, what could change if we took a different direction – one that focuses instead on place?

Places, not people, have been 'deskilled'

The current model for education policy revolves around individual students accessing educational opportunities that are thought to lead to higher income in later life. While this correlation held during the massive post-war increase of professions in need of expert knowledge, the expansive growth in graduate- level jobs plateaued long ago.

Consequently, today we see ever more graduates competing for a shrinking number of employment opportunities concentrated in expensive parts of rapidly growing cities. This in turn compounds regional imbalances as young people are compelled to leave places with fewer work opportunities to obtain qualifications and employment in city centres. The resulting pattern amounts to long-term deskilling of entire ‘left behind’ places, not people.

Today we see ever more graduates competing for a shrinking number of employment opportunities concentrated in expensive parts of rapidly growing cities.

Youth flight in north-west England

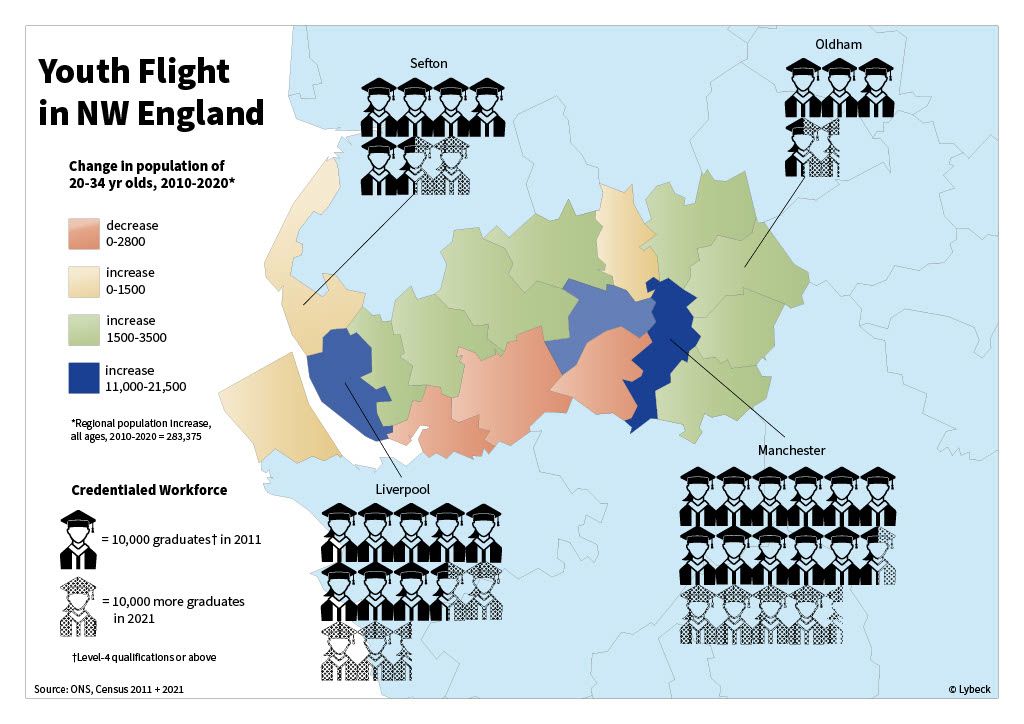

Comparing the changes in graduate and young populations between the 2011 and 2021 through Census data demonstrates this trend well. Cities like Manchester and Liverpool, with large universities and growing economies, have seen increases of 10,000 to 20,000 graduates and young people.

This compares to neighbouring areas like Sefton or Oldham that have seen much more modest increases in the numbers of graduates and young people. And some places like Halton and Warrington have experienced a decrease of young people entirely. These places are therefore getting further and further left behind in terms of skills and capacities, making it that much harder for these places to catch up and diversify economically. This discrepancy highlights the vicious cycle through which our individualist approach to educational policy can, in fact, cause regional inequalities.

The Levelling Up white paper, for example, recommends further public money to be spent in ‘Education Investment Areas’ to “ensure talented children from disadvantaged backgrounds have access to the highest standard of education this country offers”. But, if one such student in Oldham or Sefton obtained high marks on national standardised exams, they would, quite sensibly, follow their peers to where the universities and graduate level jobs are. Thus, last decade, we saw a considerable increase of young people and graduates in Manchester/Salford and Liverpool compared to their neighbouring boroughs to the North, East and West (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Youth flight in North west England, 2010-2020

Figure 1: Youth flight in North west England, 2010-2020

Co-developing place-based educational strategies for civic renewal

To disrupt this vicious cycle, we need to shed individualist social mobility assumptions and encourage local place-based strategies that link new educational provision to new work patterns and opportunities for all. No one-size-fits-all solution will work because these left behind places are not simply the obverse of advantaged city centres benefitting from economic growth and highly educated graduates.

We need to shed individualist social mobility assumptions and encourage local place-based strategies.

The long-term patterns of change in seaside towns along the Wirral and Sefton coasts are very different from those at the feet of the Pennines in Oldham and Rochdale. The latter have exhibited post-industrial decline across decades due to historic links to the production and commerce in industrial Manchester. Coastal communities are not experiencing decline due to deindustrialisation but because of the growth of package holidays and cheap air travel. Both places have developed around low-skilled work alongside the deskilling of the available local workforce, but for different reasons. Each requires a different strategy to diversify their existing economies.

The nature of present imbalances complicates this task because many of the jobs and businesses that could fill these places are not as widespread. We often see a chicken-and-egg scenario in place, where emerging businesses hesitate to relocate to towns without skilled workforces, and educational institutions find it difficult to invest in these skills without a local employer to create a realistic demand for those skills in the area.

A balance should therefore be struck between consultation with the existing local populations and stakeholders about what they would like to see and what types of work, education and places are thriving in similar and different places. National policymakers and educationalists could facilitate sharing of best practices between, for example, seaside towns and post-industrial towns. Ultimately, each place needs resources to develop their own long-term educational strategies to instigate new economic, cultural, and civic renewal locally.

Less competition, more coordination

As these regional patterns above reveal, we must move away from a competitive system wherein some individuals or local authorities succeed at the expense of their neighbours. Thus, place-based policy would require more regional coordination to integrate different local strategies. While there are many emerging opportunities in digital technologies, if every outer borough pursued the same ‘creative and digital’ strategy and limited educational provision to coding – the most likely skill to be automated in the next decade – we will have failed to turn the wheel.

Place-based policy would require more regional coordination to integrate different local strategies.

Rather, we need to see different functions spread around different regions – in patterns akin to those that developed during the industrial revolution. As 19th century Manchester shifted roles from being a production centre to a commercial hub, like spokes on a wheel, Oldham became the centre of cotton spinning, while Bolton was known for its fine yarn, Macclesfield was known for silk making and so on. So, as we re-engineer our city centres around digital and creative media clusters, we must retain a view of these historically significant adjacent places that surely have roles to play in our regional futures.

We need to encourage multi-directional mobility patterns that allow young people to move back and forth between city and town, following emergent opportunities without sacrificing income or quality of life. Hybrid working patterns post-COVID-19 could facilitate this, but this requires investment in infrastructure and know-how. Pursuit of such place-based solutions are, however, realistic and necessary, particularly after decades of individualist policies that have further widened regional inequalities.

About the author

Dr Erick Lybeck is a Presidential Fellow and Lecturer at the Manchester Institute of Education, The University of Manchester.

Running on empty

How charities are running on empty in the cost-of-living crisis - and what we can do about it

Dr Alison Briggs and Professor Sarah Marie Hall

The voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector works alongside local and national governments to provide support for residents. But alongside facing their own struggles as a result of the cost-of-living crisis, charities and community organisations are also being relied on more and more by people and local organisations. So, what approaches need to be taken to reduce demand on the sector?

The last line of defence

Charitable organisations in the UK are ‘running on empty’ as they face the relentlessness of poverty, austerity, and the rising costs of living. Our research with charitable organisations in two cities in Northern England highlights how high rates of poverty and deprivation have set the scene for the current cost-of-living crisis. This latest in a long line of crises is detrimentally impacting these organisations, who are the last line of defence against poverty.

As charitable organisations are increasingly being relied upon by welfare states to support people who are struggling to feed themselves and their families, it is essential that we question how provision of continual support – in the face of ongoing austerity and multiple crises – is experienced by those working and volunteering within this sector.

Research with local charities and community organisations

Drawing on our previous research on food insecurity and everyday austerity, we carried out further scoping research in late 2022. Our focus was local charities and community organisations in Manchester and Stoke-on-Trent, exploring the impacts of the cost-of-living crisis on their work. This included foodbanks, housing charities, social education enterprises and more.

In addition to greater numbers of people needing their support, they all spoke of more organisations needing their help.

The organisations who generously spoke with us shared experiences of increased demand for their help. In addition to greater numbers of people needing their support, they all spoke of more organisations needing their help. This included receiving regular calls for help from organisations they have not helped before, such as local schools, probation services and women’s refuges.

The cost-of-living crisis overlaps and is entangled with austerity and public spending cuts. It comes as no surprise, then, that charitable and community organisations described a collective sense of lurching from one crisis to another. The result is an intensification of all the pressures charitable organisations have seen building for a decade. Unsurprisingly, foodbanks in both case study cities are busier than ever. Crisis has become an intrinsic part of everyday life on a low income.

A perpetual state of crisis

Such increases in need are being felt by charity workers in both cities as overwhelming. Staff and volunteers remarked on how people’s experiences of food insecurity, for instance, were becoming more chronic and were no longer something that could be ameliorated by a three-day emergency food parcel. Importantly, since people were now returning week after week, foodbank staff and volunteers felt they were ‘fighting fires’ in a perpetual state of crisis themselves.

The main concern held by all organisations was being able to continue providing the level of support they have previously offered to those in need. Staff and volunteers providing food aid expressed their fears of running out of food and therefore having to turn people away.

All contributors expressed concern that they hadn’t seen the worst yet. They were also concerned about the longer-term impacts of austerity and crisis in relation to the population’s physical and mental health, wellbeing, quality of life and mortality. Consequently, they all felt that they would still need to be here in two, five or more years’ time – a fact that sat uncomfortably with them. A specific concern was voiced by foodbanks on rising child poverty and its direct and long-term impacts, which were described as ‘catastrophic’.

Staff and volunteers providing food aid expressed their fears of running out of food and therefore having to turn people away.

People-focused solutions

Based on our research, we recommend a number of people-based solutions, aimed at national government and regional policymakers.

Among them, we include the need for a move towards embedding cash-first approaches to support low- income households. The dominant charitable approach no longer works as a solution to issues of poverty. This includes direct payments from the government via Universal Credit or other legacy benefits, and cash grants provided within a wider package of support by local authorities.

Following on from their success in getting the Scottish government to adopt a cash-first approach to provide a more sustainable, long-term solution to food insecurity through addressing underlying systemic causes of poverty, the Independent Food Aid Network (IFAN) are currently working to embed cash-first approaches within every local authority in England. We see great examples of this across Greater Manchester. For example, cash-first approaches are now being used by some local organisations such as the Greater Manchester Migrant Destitution Fund, Trafford Housing Trust and Wigan Council, and came up in our conversations with local foodbanks.

We also highlight the need for urgent action to increase living standards for those on low and middle incomes to match rising costs of living. This will require a properly implemented, national living wage and an increase in wages to reflect increasing living costs and inflation. Although Manchester has now been recognised as a Living Wage city, a goal that the Greater Manchester city-region is working towards, wages continue to fail to keep up with rising inflation, causing levels of in-work poverty to increase. Charitable food providers in both Manchester and Stoke-on-Trent spoke about experiencing unprecedented demand in their communities, with the most common reason cited being the rising costs of living, followed by inadequate wages. These are clearly intersecting issues.

An effective way for local authorities to tackle record levels of child poverty in both Manchester and Stoke-on-Trent, would be to introduce universal free school meals for all primary school children.

We therefore echo calls from the Trussell Trust, the Independent Food Aid Network (IFAN), and the Trades Union Congress (TUC) for the government to take urgent action to increase people’s incomes. In the immediate term, however, an effective way for local authorities to tackle record levels of child poverty in both Manchester and Stoke-on-Trent, would be to introduce universal free school meals for all primary school children, as the city of London has recently done.

Until these basic conditions are met, we expect to see the cost-of-living crisis spiral further – and for charitable organisations to be filling from an empty bucket.

About the authors

Dr Alison Briggs is a Research Associate in Geography at The University of Manchester.

Professor Sarah Marie Hall is a Professor of Human Geography at The University of Manchester. She leads the Austerity and Altered Life-Courses project, a four-year study across the UK, Spain and Italy.

Mapping the divide

Learning from the landscape of local economic performance

Professor Cecilia Wong and Dr Wei Zheng

Inequality can be sliced many ways. A key aspect of the UK’s picture on inequality falls starkly along spatial lines of geography. So how can mapping spatial differences make policymaking more effective and targeted?

Place-based approaches

It is encouraging that the government has recently committed to place-based policymaking to tackle entrenched spatial inequality. However, there has been a lack of spatial analysis to pinpoint the different challenges encountered in local areas. This is essential to inform the policy debate. There is a need to develop robust spatial analysis by bundling key indicators. This will provide a more grounded understanding of issues and permit benchmarking by contrasting and comparing places.

In addition, visualisation of the different spatial patterns through mapping analysis can lay bare different socio-economic conditions, as well as showing the neighbouring context between different places.

Visualisation of the different spatial patterns through mapping analysis can lay bare different socio-economic conditions.

Illustrating spatial inequality by numbers

This can be illustrated by taking labour productivity and employment change as an example. There has been intensive debate over the so-called ‘productivity puzzle’, relating to the UK’s significantly lower level of productivity growth after its sharp fall during the 2008 global financial crisis. This puzzle is made all the more intriguing when considering the growth in employment over the same period.

Persistent spatial divide of labour productivity

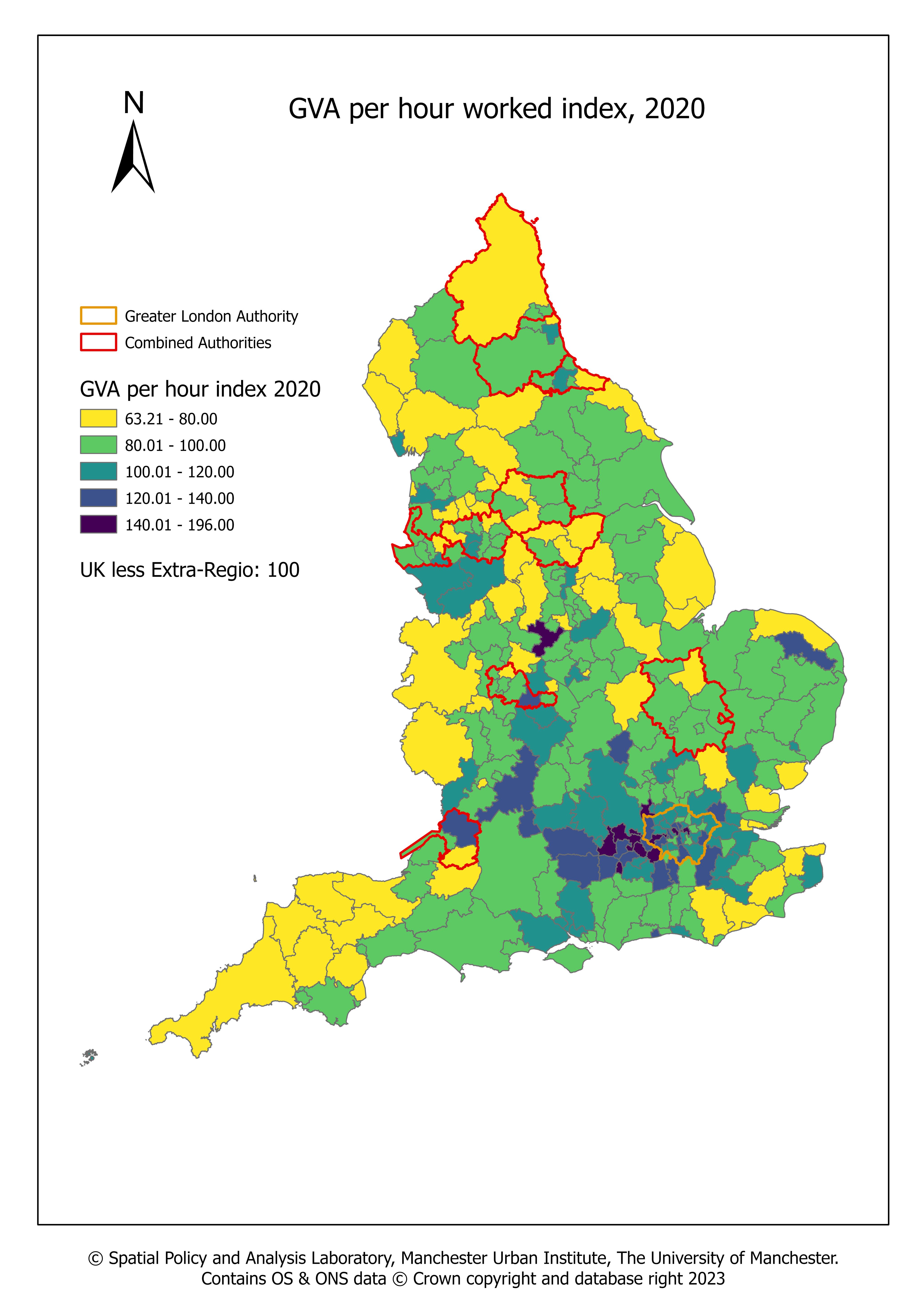

The most recent small area labour productivity data (2020), shown in Map 1, confirms the persistent spatial divide between London and the Southeast regions and the rest of the country in terms of gross value added (GVA) per hour worked. There is also a north-south divide among the combined authority (CA) areas, with the West of England and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CA areas out-performing the others. Map 1 also highlights the fact that there were major spatial variations in productivity levels across different local authority districts (LADs), even within the CA areas.

Map 1: GVA per hour worked index, 2020

Map 1: GVA per hour worked index, 2020

In numerical terms, we can see this inequality more starkly. In 2020, GVA per hour rate in Greater London was £47.25, followed by West of England’s £34.71 and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough’s £32.31.

Recent trends in labour productivity

Between 2015 and 2019, five CA areas outside southern England enjoyed growth in GVA per hour worked by over 4.4% in real terms. They were West Yorkshire, North of Tyne, Greater Manchester, the North East, and West Midlands - outperforming Greater London’s 3.19% increase. Due to this upward trajectory, Greater Manchester’s labour productivity has been catching up and reached a level of £33.22 value added per hour worked in 2019 – the highest productivity outside southern England.

However, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on labour productivity has been detrimental to all areas, ranging from -4.79% in Greater London to -6.93% in South Yorkshire between 2019 and 2020.

The situation was particularly challenging in South Yorkshire, Liverpool City Region and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CA areas as their GVA per hour worked in 2020 was even lower, in real terms, than in 2004.

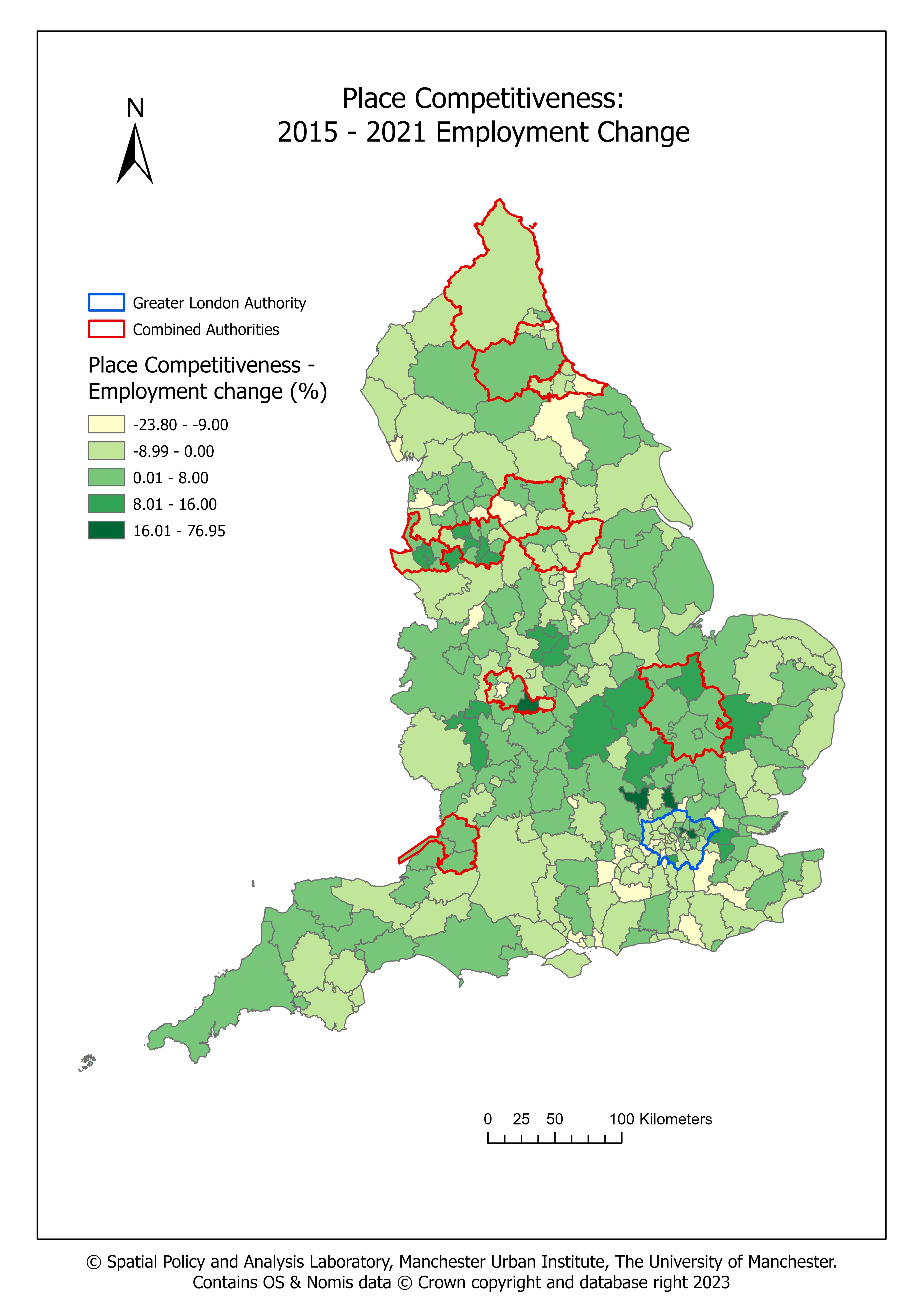

Trends and underlying factors of employment growth

Alongside GVA, we can look at employment growth patterns. These have been mixed across CA areas, ranging from 0.24% in Tees Valley to 12.94% in Greater Manchester between 2015 and 2021. While the southern CA areas in West of England (12%) and Cambridgeshire and Peterborough (9.09%) exhibited high growth, there has been an emergence of a high performing Mersey Belt across Greater Manchester (12.94%) and Liverpool City Region (11.04%) CA areas.

By drilling down into the components of employment change, the analysis shows that variations in employment growth during 2015-2021 were mainly related to differential place competitiveness conditions (total regional growth minus the national growth and industrial mix effects). This accounted for 98.2% of local variations whereas local industrial mixes (regional growth explained by that industry’s growth at the national level) accounted for 1.3%. The relatively high levels of employment growth witnessed in Greater Manchester and Liverpool City Region were largely attributed to their increase in place competitiveness advantages across most of their local authorities (see Map 2). The West of England CA area, however, enjoyed growth from both its favourable industrial mix and its increased place competitiveness.

Since local competitiveness condition is the residual value after taking account of the national economic situation and the industrial mix, working out what constitutes these conditions in individual areas requires in-depth local knowledge.

Map 2: 2015-2021 Employment Change

Map 2: 2015-2021 Employment Change

Differential spatial trajectories require different policy action

The analysis here illustrates the complex trajectories of local economic performance when examining different economic indicators. While some areas score well on employment growth, their GVA level remains low with stagnant growth in both GVA and employment (for example, South Yorkshire). Others are doing well on GVA level but becoming less competitive in their place conditions (such as some London boroughs). This data can inform place-specific policymaking to improve economic performance in these areas.

The analysis here illustrates the complex trajectories of local economic performance when examining different economic indicators.

While the analysis largely confirms the paradoxical relationship between productivity and employment growth, it does highlight some key messages. GVA per hour worked is associated with the concentration of specific types of high-paid industrial sectors such as the information and communication sector; the professional, scientific and technical sector; aerospace; and car industries. Different places do perform differently on these indicators and as a result they will require different policy action. Emerging spatial clusters of areas sharing similar characteristics could be identified through spatial mapping analysis to foster synergy in collaborative strategy.

We can build on this data to create even more detailed pictures of different areas. For example, over a quarter of the population was found to be economically inactive in some LADs across the Greater Manchester CA area including Manchester, Bolton, Oldham and Salford. Economic inactivity is also found to be closely associated with unemployment levels and lower life expectancy. These all have implications on labour productivity and economic performance of places and should be factored into place-based policymaking.

Economic inactivity is also found to be closely associated with unemployment levels and lower life expectancy.

Good policy on place-making needs to have strategic vision. This type of spatial analysis highlights different local challenges and offers opportunities for more creative spatial thinking to exploit synergies and partnership working across different places, both within and beyond local and combined authority boundaries.

About the authors

Professor Cecilia Wong is a Professor of Spatial Planning and Director of the Spatial Policy & Analysis Lab at The University of Manchester.

Dr Wei Zheng is a Lecturer in Planning and Environmental Management at The University of Manchester.

Both Cecilia and Wei are researching spatial inequalities in the UK and working on a five-year project examining the relationship between public health, transport and urban planning in the Greater Manchester City Region.

With special thanks to our contributors:

Jamie Anderson is a Research Fellow in Geography at The University of Manchester.

Joanna Barrow is a Research Assistant in the Department of Geography and Manchester Institute of Education at The University of Manchester.

Alison Briggs is a Research Associate in Geography at The University of Manchester.

Louisa Dawes is a Senior Lecturer in Education and joint convener of the Teacher Education and Professional Learning (TEPL) Research Group at the Manchester Institute of Education in The University of Manchester.

Carl Emery is a Lecturer in Education and co-leader of the Power, Inequality and Activism Research Group at the Manchester Institute of Education in The University of Manchester.

James Evans is a Professor of Geography at The University of Manchester and the Director of the Manchester Urban Institute.

Francesca Gains is a Professor of Public Policy at The University of Manchester.

Lord Kerslake served as a crossbench peer in the House of Lords from 2015 until 2023. He also served as the chair of the UK2070 Commission.

Sarah Marie Hall is Professor of Human Geography at The University of Manchester.

Neil Humphrey is Professor of Psychology of Education in the Manchester Institute of Education, The University of Manchester, and is the academic lead for the #BeeWell programme.

Arbaz Kapadi is a Research Associate in the Division of Psychology & Mental Health at The University of Manchester.

Eric Lybeck is a Presidential Fellow and a Lecturer at the Manchester Institute of Education, The University of Manchester.

Sherilyn MacGregor is Professor of Environmental Politics in the Sustainable Consumption Institute, The University of Manchester, and leads the Leverhulme Trust funded project Towards Inclusive Environmental Sustainability (TIES)

Luke Munford is a Senior Lecturer in Health Economics at The University of Manchester.

Liz Richardson is Professor of Public Administration at The University of Manchester.

Udeni Salmon is a Research Associate in the Sustainable Consumption Institute at The University of Manchester.

Cecilia Wong is Professor of Spatial Planning and Director of the Spatial Policy & Analysis Lab at The University of Manchester.

Wei Zheng is Lecturer in Planning and Environmental Management at The University of Manchester.

Analysis and ideas on place-based policymaking.

Curated by Policy@Manchester

Read more and join the debate at blog.policy.manchester.ac.uk

#PowerInPlace

June 2023

The University of Manchester

Oxford Road

Manchester M13 9PL

United Kingdom

The University of Manchester is advancing our understanding of the world in which we live, addressing inequalities to improve lives. As we have done for almost two centuries, The University of Manchester is leading the way in addressing all aspects of inequality, from poverty to social justice, from living conditions to equality in the workplace. Bringing together some of the best academic minds in applied medicine, business, law, social sciences and the arts, we're meeting these challenges head on, creating and sharing knowledge to understand our world and directly change it for the better.

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Manchester.

Recommendations are based on authors’ research evidence and experience in their fields. Evidence and further discussion can be obtained by correspondence with the authors; please contact policy@manchester.ac.uk in the first instance.

The photos included in the ‘Building wellbeing into place-based urban regeneration policymaking’ article were taken by the lead author, Dr Jamie Anderson.

Design and layout coppermedia.co.uk