Lessons from Lockdown

Analysis and recommendations for the future

Foreword

Professor Francesca Gains

All our lives have changed fundamentally and irrevocably since the spread of the new, highly infectious and deadly coronavirus (COVID-19). As infection spread across communities, countries and continents, the UK like elsewhere went into lockdown. City streets and supermarket shelves emptied and whilst key workers kept vital services going, many of us discovered new online platforms to keep in touch with family, friends and colleagues. Throughout the first 100 days of lockdown, the Government’s daily coronavirus press briefings made epidemiologists and statisticians of us all.

The policy landscape, locally, nationally and internationally has fundamentally changed in the weeks since lockdown began in March. Yet many of the issues which confronted policymakers in the immediate stages of lockdown, and the urgent policy problems which the pandemic has exposed, were agendas where the University was well placed to contribute – indeed to continue and deepen our existing policy engagement.

As the post lockdown period got underway, Policy@Manchester published blogs from researchers across our Faculties. The blogs in this collection aim to bring research insights and policy solutions to the attention of our key stakeholders to help in their work of finding policy solutions to a post COVID-19 world. Whether it be research directly addressing the scientific, medical and public health challenges of tackling COVID-19; the trade-offs between economic activity and sustainability; the digital challenges raised by moving life on line; the ongoing contribution of our science and engineering research to developing the regional economy; or on the economic, societal and political issues facing policymakers locally, nationally and internationally around how the world of work, leisure, and governance might change. Crucially, our research helps to bring together how scientific and technological developments and human behaviour interact across all policy agendas.

As we move into a phase of learning to live with the impact and consequences of COVID- 19, we hope you find this collection of lockdown blogs useful. We would be glad to follow up so do please get in touch with us.

Timeline: A glimpse through the pandemic

What COVID-19 tells us about the value of human labour

Abbie Winton and Professor Debra Howcroft

In the wake of the coronavirus outbreak, a radical reassessment of what is considered ‘key work’ has taken place. For many key workers, however, this status is not reflected in their salary, employment rights, or social perception. Here, Abbie Winton and Professor Debra Howcroft, from the Work and Equalities Institute, discuss the disproportionate risk/reward equation key workers – particularly women – face, how the COVID-19 crisis will impact their future, and what policymakers can do to address inequalities at work.

On 19 March, the UK government published a list of ‘key workers’ considered to be critical to the provision of services during the COVID-19 crisis. These workers amount to 7.1 million adults across the UK, the majority of whom are female. Many ‘key workers’ receive the National Living Wage, the minimum wage set by the government for over 25’s. These workers are vital for society to function, yet the degradation of the employment relationship illustrates how the value of labour is not dependent on an impartial measure of supply and demand but is constructed by the social context within which it is embedded. In light of the current crisis, a radical re-think of how labour is valued – both socially and financially – is needed, leading to policies which ensure that key workers are paid and protected in a way that reflects their critical contribution to society.

Gendering of ‘key workers’

Of the designated ‘key workers’ in the UK, 60% are women (compared to 43% of workers outside of these industries). As a consequence, 77% of workers in occupations identified as being at ‘high-risk’ of contracting COVID-19 are also women, underlining their role in frontline work.

The predominance of women as ‘key workers’ is a result of the historical normalisation of ‘women’s work’, and persistent structural inequalities within waged and unwaged work. Numerous occupations remain largely feminised and are often valued less than occupations associated with ‘men’s work’, despite requirements for equivalent skill levels (eg social care and construction work require comparable NVQ levels).

Feminist theory informs us that how society perceives, and constructs skills is a pervasive determinant of value as opposed to the actual skill required to do the job. Feminised roles have long been deemed ‘unskilled’ or ‘low skilled’ as they are seen as an extension of unwaged work in the domestic sphere (eg health, social and child carers, cooks, cleaners). Therefore, although many of these feminised ‘key roles’ provide a critical service, they continue to be undervalued.

The mismatch of skill and value

While some key workers are employed in ‘skilled’ professional roles, many are categorised ‘unskilled’ or ‘low skilled’ according to Standard Occupational Classifications (eg food production, sales and delivery, social and other healthcare roles). While the social value of certain roles fluctuates depending on the needs of society at any given time, the financial value of work remains bounded by the social perception of the skills which the role demands. This bias which shapes evaluations of skills is likely to deepen inequalities and the way in which work is valued.

What is the future for ‘key roles’?

While some suggest that COVID-19 generates uncertainty for future investment in automation, a survey of employers shows they are accelerating plans to automate roles while workers stay at home. Future uncertainty is of concern for women as they are likely to be disproportionately impacted by processes of automation given their concentration in particularly vulnerable roles, such as sales and cashier roles.

Considering the example of food retail, the demands of the crisis has demonstrated the value of human labour, as well as the importance of skills which are commonly overlooked and undervalued. For example, activities which require non-cognitive skills (shelf-stacking, picking and packing), or require an element of ‘human-touch’ (helping elderly and vulnerable members of the public, monitoring social distancing, intervening in practices of bulk buying) remain difficult to automate.

In the UK, to cope with increases in demand, 45,000 temporary jobs have been created in food retailing and existing roles have intensified, both in terms of consumer expectations and working-time (exemplifying many ‘extreme work’ characteristics, such as extended working hours, increase in demands for multi-tasking, and the regulation of emotion of both colleagues and customers). In the US, 100,000 new jobs have been added in Amazon’s fulfilment and distribution network, even though many of its warehouses rely largely on robotics systems. Therefore, while employing people often remains cheaper than investing in new technology, certainly in the short-term, a lesson we have learnt is that technology alone cannot save us in a crisis.

What policymakers can do

Given the increasing prevalence of precarious working conditions (such as zero hour contracts, underemployment, and unstable hours) full employment rights and adequate social protection should be extended to all key workers. Gendered assumptions around skills in the workplace require an overhaul, so that traditionally feminised occupations receive appropriate recognition and recompense.

In parallel to this, a re-assessment of social value is required so that key workers operating on the front-line, many of whom are risking their health, are fairly rewarded by pay which reflects this. In times of crisis we see how those who are critical to the functioning of society are largely undervalued and often low-paid. The public response to ‘clap for carers’ symbolises an appreciation of social value from grassroots level, which will hopefully influence policymakers and result in a levelling up that is long overdue.

The Standard Occupational Classification needs to be re-evaluated in line with technological advances shaping both the supply and demand of skills, with a focus on the way in which skills which defy automation are valued. Investment in technological change is to be welcomed, but on condition that potential productivity gains are redistributed with a view to creating a more equal society.

Originally published 7 April 2020

Planning and managing service delivery in the NHS: looking to the future

Professor Kath Checkland

COVID-19 has reinforced the necessity of effective planning of health services, treatment and prevention capacities in primary and secondary care, and both protecting and optimising our healthcare workforce. Here, Professor Kath Checkland reflects on the renewed centrality of “commissioning” to health policy debates that will follow in the wake of the pandemic, and draws lessons from research here at Manchester for the policymakers and practitioners who will need to address this debate in the months to come.

The organisation and management of the NHS can seem to be a dry subject, full of esoteric language and highly technical details. Acronyms abound, with NHSE overseeing CCGs which in turn support PCNs whilst contributing to ICSs, with CQUINs offering incentives – with the LTP setting out the strategy for the next 10 years. And if you understand that sentence then you have clearly spent far too much time reading about government policy!

However, one thing that the current crisis has taught us is that the oversight and management of the NHS matters. Planning – usually known in the NHS as commissioning – is the function which ensures that the right services are available for the right people at the right time. Providing sufficient capacity in both hospitals and community services, and co-ordinating between different types of care providers to make sure that patients experience joined up services require complex systems and oversight. As the NHS and social care services adapt to and recover from the pandemic, it is important to consider how planning works, and how it may need to change.

Development of organisation and planning from 2012

In 2012 a vast reorganisation of the NHS took place which affected all parts of the system. Our team has been researching these changes for the past 8 years and in a recently published book we offer a comprehensive overview of the changes made and their impacts on the governance, accountability and functioning of the health system in England.

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 distributed responsibility for commissioning services to a much wider range of organisations, and required service providers to compete with one another to a greater degree than in the past. Public health was moved outside the NHS to Local Government, and a new Arm’s Length Body, NHS England, was established to oversee the service as whole. The result was a significant fragmentation of care planning across the NHS, with some emerging evidence of a potential deterioration in the provision of some types of care.

Less than 10 years after its enactment, many of the principles underlying the Act have been discarded, with a move away from competition and a new focus on collaboration and integration of care. However, the legislative structures put in place in 2012 remain, and the new collaborative structures which are being built rest upon agreements and partnerships rather than being enshrined in statute. Our research found that confused lines of accountability could be a problem, and that skilled managers with a good knowledge of their local area were vital in the planning process. The fragmentation which resulted from the Health and Social Care Act was at least partially mitigated by the hard work of skilled commissioning managers who, in their words, ‘knitted the system back together’. We also observed that different functions require activity on a different scale, with planning of primary care services needing a much more local focus than larger scale hospital reorganisations and collaborations to deliver more specialised services.

The building blocks of the more collaborative system set out in the NHS Long term Plan of 2019 include collaborations across populations of 1-3 million, known as Integrated Care Systems (ICS), and local neighbourhood collaborations between GP practices and other community-based services, known as Primary Care Networks (PCN). ICSs are focused upon the big issues of resource distribution between hospitals and the best way to organise services such as emergency care and specialist surgery. PCNs are focused upon how best to provide services outside hospital, with GP practices working together with other community services to provide comprehensive services and hopefully keep people out of hospital. Clearly the current pandemic will have affected these developments, with collaboration at all levels even more important in the current emergency.

Organisation and planning: lessons for the future

So what can we learn from our research to date which may be relevant to regional collaboration (in Integrated Care Systems) and in local neighbourhood working (in Primary Care Networks) as they develop and work together to manage the crisis?

The NHS which emerged from the Health and Social care Act 2012 is a very complicated one, with overlapping layers of regulation and accountability. The Covid-19 crisis has led to a centralisation of many aspects of NHS decision making, and this may well be appropriate for short term crisis management. However, as the NHS returns to normal it may be that this is an appropriate time to consider the level within the system at which different types of decision are made. Our studies have raised the question as to whether the regional level of co-ordination should be put on a statutory footing, as used to be the case with Strategic Health Authorities. The different pace and impact of the pandemic in different areas suggests that a regional tier of management with a clearly defined role, responsibilities and lines of accountability may offer considerable advantages in the recovery period and in the longer term.

Our research highlighted the complex regulatory structures to which NHS organisations are subject, from national inspection regimes to the application of EU law on procurement. The current crisis has led to the short term suspension of many regulatory requirements, such as individual practitioner revalidation and CQC inspections. It is much easier to increase regulation than it is to reduce it, and this may be an opportunity to critically examine each element of the regulatory system to consider how and in what circumstances it adds value or prevents avoidable harm, only re-introducing those where a clear rationale can be described.

Our research has shown that the planning and management of primary care requires detailed local knowledge, and the pre-Covid 19 push for Clinical Commissioning Groups to merge and cover much larger populations may make this more difficult. In the aftermath of the pandemic there will be an opportunity to critically examine how local services adapted and what factors helped them to do that. A measured consideration of what planning functions need to take place over what geographical scale would be of value, and could inform future decisions as to optimum CCG size.

One of the drivers of CCG mergers is the reduction in management costs. All of our studies have shown that high quality management is of vital importance in the delivery of high quality NHS services, and that personal knowledge and relationships underpin the planning and delivery of these services. Valuing managers and the relationships that they have built should be the cornerstone of the NHS as it builds for the future.

Originally published 26 May 2020

Furlough, fraud and the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme

Pete Duncan and Professor Nicholas Lord

The Government-implemented Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) supports companies in their attempts to ride out the COVID-19 pandemic, permitting them to place employees on a temporary leave of absence known as ‘furlough’, and claim state aid to pay furloughed staff either 80% of their usual wages or up to £2,500 per month, whichever amount is lower. Whilst furloughed, employees are not permitted to conduct work for their employer. Pete Duncan and Professor Nicholas Lord discuss how dishonest CJRS claims might be made and how the Government can improve and make best use of the limited data they have to better protect public funds from fraudulent manipulation.

Whilst it comes at great cost to the taxpayer, the Job Retention Scheme provides (some) companies and workers with much-needed financial protection. It provides a lifeline to businesses whilst they tread water, ready to spring into action when the time is right. A number of drawbacks and ambiguities have been raised, but one downside that has been minimally discussed is the opportunity the Scheme creates for defrauding the state.

Figure 1. As the Job Retention Scheme increases in cost for the Government, stopping potential fraud is of paramount importance

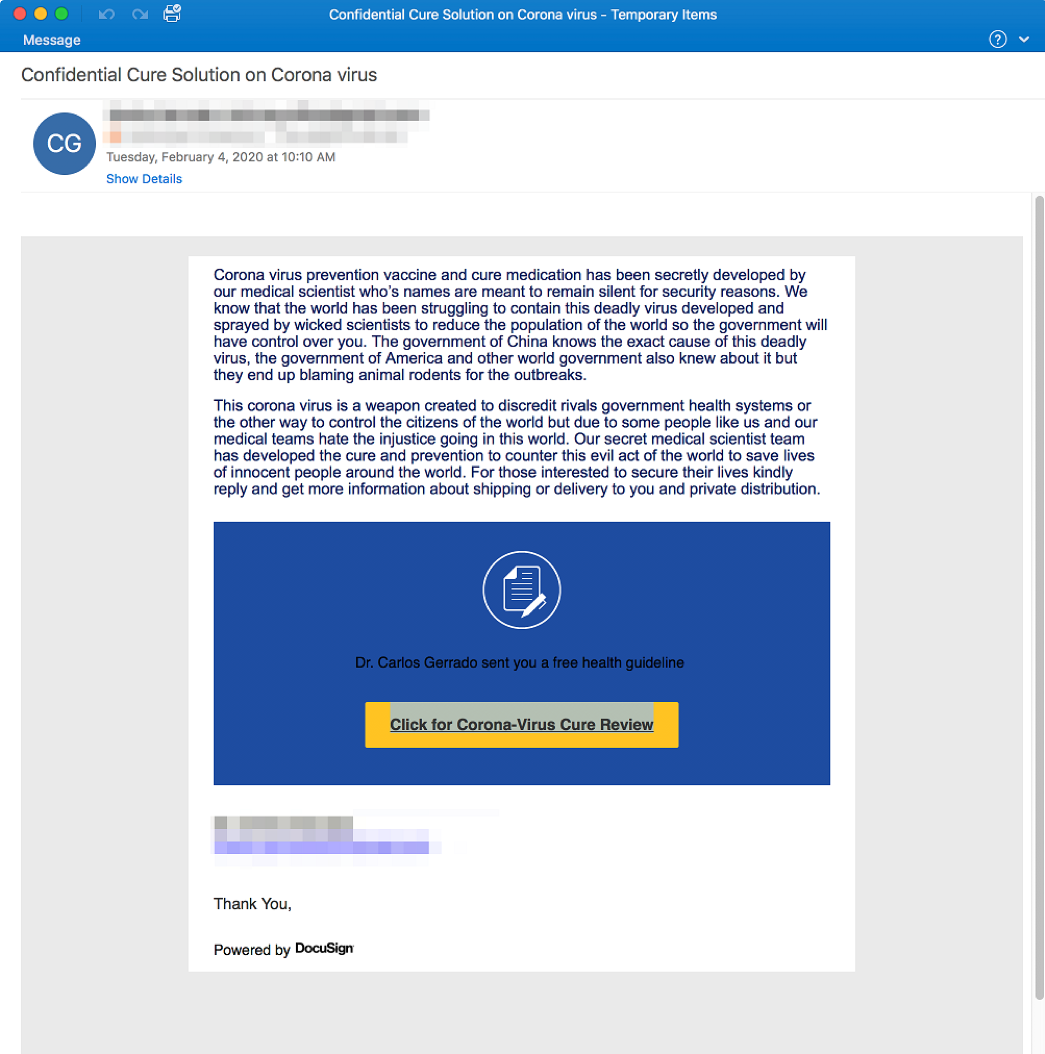

Furlough frauds

Fraud can be broadly defined as dishonesty or deception for illegal gain, and usually takes the form of a false representation, an abuse of position, or a failure to disclose information, as covered in the Fraud Act 2006.

For instance, an employer claiming CJRS aid for furloughed staff, but encouraging or coercing those employees to continue working when they should not (perhaps through manipulation or the threat of job losses), would constitute fraud by false representation. In this way, deviant employers transcend ‘business as usual’ into a realm where business continues as normal but usual staffing costs are drastically reduced. This would be especially easy to organise in small companies with few co-offenders and little customer interaction.

Similarly, an employer claiming aid via the Scheme but withholding some (or all) of the received funds from their employees would constitute an abuse of their specific position of power, as they would be promoting their business interests at the expense of the employees they are obliged to safeguard. This might be more difficult to organise as victimised employees would be more likely to report the fraud.

These frauds can clearly harm Government and tax payers (as public funds are illegally obtained), as well as individual employees in need of financial support. There are also likely to be harms to wider business and social interests, as ultimately these monies will be repaid through taxes and trust in business may be eroded.

(In)credible oversight?

We expect that most employers will not pursue fraudulent claims, either on the basis of social responsibility, or through more instrumental mechanisms to prevent furloughed employees from working (eg by cutting off access to employees’ email accounts). However, it is without doubt that in some organisational contexts and with the absence of credible oversight, motivated offenders will take the fraudulent opportunities the Scheme has created. The Government has implemented some interventions to safeguard the public purse from this exploitation, but there are a number of issues that need to be considered.

As of 29 May, the anonymous CJRS fraud reporting system had received nearly 1900 reports of suspected manipulation. Whilst some reports could be duplicates entered by multiple individuals with knowledge of a single fraud, the true extent of CJRS manipulation is likely much higher due to the numerous barriers affecting an individual’s likelihood to report, even when they have been directly victimised.

For instance, even if anonymity was assured (which seems hard to guarantee, especially in smaller organisations), sanctions for companies found to be making fraudulent claims to the CJRS could end up harming those anonymously blowing the whistle. With predicted rises in unemployment on the horizon, potential whistle-blowers might decide not to report for fear that Government sanctions might put their employer out of business (especially if that business was struggling before the pandemic). For reasons such as this, in its current guise the CJRS reporting system cannot itself be considered credible oversight to safeguard against furlough fraud.

The Government has also attempted to control furlough fraud by indicating claims might be audited by HMRC, but it is unclear how this process will work. The sheer volume of demand the Scheme has attracted means auditing all claims would likely be an improbable and costly endeavour.

Improving investigations of fraud

Furthermore, the majority of fraud investigations will be conducted retrospectively as HMRC have suspended some tax investigations due to capacity issues created by implementation of the CJRS. This is inherently problematic as attempting to recoup funds lost through fraudulent claims is costly, uncertain, and politically undesirable if large fines risk putting firms out of business (amendments to the Finance Bill 2020 give HMRC powers to fine persons deliberately making incorrect claims and to hold company officers liable).

HMRC’s retrospective response should integrate harm assessment with evidence and intelligence-led investigation. First, those reports indicating the greatest harms to employees and the public purse should be prioritised. Alongside this, rigorous analysis of data on known CJRS frauds to build an understanding of associated red flags will enable HMRC to efficiently and systematically identify other reports that are more likely to be fraudulent. For instance, are there common features or patterns evident in those cases? Are certain sectors or industries more susceptible to furlough fraud? Such an approach would, of course, only build an understanding of the frauds that are actually reported. Second, therefore, tip-offs from whistleblowers should be incentivised as these ‘insiders’ are likely to provide the most credible insights into company deviance. Third, leniency should be offered to early disclosers who report their frauds to HMRC.

The CJRS has recently been extended until October. This gives the Government more time to consider how it can better collect and make best use of data to develop a systematic and effective procedure for investigating furlough fraud once economic activity has returned to some degree of normality.

Originally published 22 June 2020

Prioritising play to promote wellbeing

Cathy Atkinson and Marianne Mannello

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Article 31 states children have the right to access play, rest and leisure. With the uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, play opportunities are vital to helping children make sense of their experiences, problem-solve, reconnect with their peers, and promote their own wellbeing. Cathy Atkinson, Senior Lecturer in Educational and Child Psychology at The University of Manchester, and Marianne Mannello, Assistant Director of Play Wales consider the important role of children’s play during lockdown in promoting positive mental health, and discuss the ways schools can promote play when they reopen.

Why play is important to children’s wellbeing

Last year, before the current lockdown situation, researchers at The University of Manchester, alongside specialist partners, developed a position statement for the British Psychological Society highlighting the importance of play in helping children deal with uncertainty and challenge, regulate emotions and experience fun, enjoyment and freedom. In an accompanying video, children explained why they valued play and how important it was to them.

Play can help promote wellbeing in terms of helping children to:

· Make sense of what has happened to them;

· Deal with emotional upset and regain control of their lives;

· Experience normality and pleasure during times of upheaval, loss, isolation and trauma;

· Foster resilience through promoting emotional regulation, creativity, relationships, problem-solving and learning.

Play and wellbeing during lockdown

Play has not stopped for lockdown and is as important as ever, as it is children’s way of supporting their own health and wellbeing. Children will find opportunities for play, even in the most adverse of circumstances and parents can support this through:

· Time – enabling children to play freely and valuing play;

· Space – creating opportunities for play using everyday objects, and recognising that play can sometimes be noisy and boisterous;

· Permission – acknowledging that it is okay for older children to play, for children to play alone, and for children to decide how they want to play.

However, children’s opportunities for play will be affected by their family’s circumstances. For example, in situations where parents are expected to work, where there is limited indoor or outdoor space, or stress from loved ones being distant or unwell, opportunities might be compromised.

Transition back to school

There have been recent calls by leading academics for schools to prioritise play when they reopen. This may be particularly important for children who have experienced difficult circumstances during lockdown, such as parental separation, loss, grief or trauma.

To highlight the importance of play, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child published General Comment 17, highlighting how play provides a means by which children can externalise difficult, unsettling or traumatic life experiences and offer specific guidance to schools as to how this might be achieved.

Before the coronavirus outbreak, concerns about diminished opportunities for play, especially for vulnerable groups such as children with special educational needs and disabilities, and children living in poverty had already been highlighted because curriculum pressures have led to reduced opportunities for play in schools.

Children cannot learn effectively when they are stressed or overwhelmed. Studies of brain development indicate that children who have experienced trauma find it difficult to maintain attention, remember things, manage behaviour and regulate emotions, and can have mental health issues in adolescence and adulthood. There is continued uncertainty about exactly when children will return to school and this may well vary across the different countries and regions of the United Kingdom. However, we would ask that when schools do reopen, that it is recognised that this is not the time to play ‘curriculum catch-up’. Children need time to readjust to school life and reconnect with teachers and peers, rather than worrying about learning.

How schools can support wellbeing through promoting play

The challenge now for the Government and devolved nations is to balance reopening schools and keeping children, parents and teachers safe, whilst maintaining the benefits of play to wellbeing. In light of guidance from the Office for National Statistics, that children are just as likely to catch the virus, any planned return would need to be handled extremely carefully. But extreme physical distancing measures such as those pictured in France last week will inevitably do more harm than good to already vulnerable children.

We suggest that the Departments for Education across the UK could produce short-term guidance for schools to help them support children’s wellbeing and physical safety. This guidance could include UN advice, as noted in General Comment 17, in the following four areas to promote children’s right to play.

1. Physical environment of settings – The playground environment can be adapted to enable safe, creative play, and make the school more play-friendly. Schools can use fun equipment and/or visual referencing to promote physical distancing. Where feasible, could the playground be available for the whole day to enable extended outdoor access for more children, or could the school field or forest school site be better utilised?

2. Structure of the day – The guidance could support schools to find ways to develop a more responsive and flexible structure to allow teachers to adapt to the needs of their pupils and provide more time and opportunity for outdoor play and learning.

3. Curriculum demands – Given what we know about the impact of trauma and upheaval on learning, we would recommend that curriculum demands on children and teachers be reduced, to allow opportunities for play, emotional growth and social connection. Child-led learning experiences which facilitate free play could ensure no child gets left behind. As cultural and arts activities have been restricted during lockdown, how can these be reintroduced via school curricula?

4. Educational pedagogy – The UN describes the importance of learning environments being active and participatory. Schools can make playful activities central to learning, for older children as well as for those in the early years. Recent research from The University of Manchester found that where the boundaries between schoolwork and play were more ‘blurred’, children felt a greater sense of control over their own learning experience.

Playing is the most natural and enjoyable way for children to keep well and be happy. It is their way of supporting their own health and wellbeing. It is vital that efforts to improve wellbeing in schools should focus on providing sufficient time and space for play.

The UN states that, for children, play “can restore a sense of identity, help them make meaning of what has happened to them, and enable them experience fun and enjoyment.” Recognising the importance of play at this point in time could be an enormous step forward, in terms of protecting the mental health and wellbeing of our children, and of future generations.

Originally published 21 May 2020

Locked down by inequality: Why place matters for older people during COVID-19

Christopher Phillipson, Camilla Lewis, Tine Buffel, Patty Doran and Sophie Yarker

Older people have borne the brunt of deaths from COVID-19, whether in hospital or in care homes. At the same time, the coronavirus emergency sits alongside a crisis in many of the communities in which older people live. Here, Chris Phillipson, Camilla Lewis, Tine Buffel, Patty Doran and Sophie Yarker examine how the pandemic will affect older people living in areas of multiple deprivation.

Where you live matters greatly for your quality of life in older age; it matters also for whether you are protected from COVID-19. The Marmot Review, examining changing health inequalities between 2010-2020, highlighted the increase in deprivation affecting many parts of England. Area deprivation is also associated with higher levels of social exclusion in later life, for example to services, participation in leisure activities, and relationships with friends and family. Quality of life will also be affected by housing conditions – especially important given restrictions imposed by social distancing.

Nearly three-quarters of a million people 75 and over live in what are termed ‘non-decent homes’ – a higher proportion than any other age group. The most common reason is the presence of a serious hazard posing a risk to the occupants’ health or safety, such as inadequate heating or a fall hazard. Over a million over- 55s are living in a home with at least one such problem. It is hardly surprising that the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has reported that those living in the poorest parts of England and Wales are dying at twice the rate from COVID-19 compared with those in more affluent areas.

Figure 2. Deaths in the most deprived areas are considerably higher than in more wealthy neighbourhoods

Double lockdown

As the impact of coronavirus grows, older populations who are social distancing may be doubly locked down – suffering the effects of social isolation whilst living in places affected by substantial cuts to public services. This challenges us to ask fundamental questions about the changing nature of our communities, and the responses necessary to assist older people during the pandemic. With the likely continuation of social distancing rules in some form, the implications for neighbourhood support requires urgent attention. The danger at the present time is that the pressures facing communities are being over- simplified through two competing narratives:

· The first portrays a romanticised view of neighbourhoods coming together against a ‘common enemy’, symbolised by the weekly applause for NHS workers, along with the deployment of an army of volunteers stepping forward to support vulnerable groups.

· The second highlights reports of outbreaks of unrest caused by the constraints of the lockdown, suspicion of neighbours flouting the guidelines, and selfish behaviour in supermarkets.

It is certainly the case that many social groups have emerged to provide support for those whose isolation has been compounded by COVID-19. In some cases, this builds upon existing voluntary and mutual aid organisations which have replaced services from the local welfare state. But it is important not to ignore evidence about the long-term changes affecting communities. Roughly at the same time as COVID-19 started to spread across the country, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) provided an update on its review of trends in social capital in the UK. The results highlighted significant developments over the past decade, with evidence of less positive engagement with neighbours, less help being given to groups such as older people, and a reduced sense of belonging to the communities in which we live.

The findings from the ONS should not come as a surprise: the last ten years has seen an upsurge in inequalities within and between neighbourhoods in the UK, with zones of affluence and poverty existing side by side. But the majority of attention has focused on growing disparities between income groups, rather than the impact on relationships in everyday life. COVID-19 and measures such as social distancing, will ‘stress test’ the ability of communities to work together to protect vulnerable groups. The pandemic underlines the degree to which social processes relating to inequality, discrimination and racism contribute to the distribution of illness and deaths caused by COVID-19. Social interventions in marginalised communities are now urgently required to strengthen defences against subsequent waves of the virus.

Community development policy

We would argue for a new community development policy to assist the most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK. The policy will need to comprise:

Funding: Disinvestment in social infrastructure has resulted in the closure of libraries, day care and community centres. Such resources are essential for providing informal spaces for people to meet, and both support and empower vulnerable groups. Deep cuts to local authorities over the past decade have resulted in significant financial pressures on all public services. Local authorities suffered a 49.1% real terms reduction in central government funding from 2010 to 2018.

Areas of multiple deprivation must be prioritised in future government spending. Such funding will need to be complemented by a national strategy to tackle health inequalities, drawing on lessons from the Marmot Review, and studies showing the detrimental impact of neighbourhood deprivation on older people’s quality of life. Targeting older people at risk of isolation, by focusing resources on socially excluded places, must be an essential part of the government’s recovery strategy.

Locally based partnerships: Interventions which have the most impact are those designed to meet the specific needs of communities, in situ. A one-size-fits-all approach to community must be rejected, in favour of tailored support to meet the needs of different groups through encouraging dialogue between local residents, voluntary organisations and the public sector.

Local authorities need to give urgent attention to developing new models of neighbourhood working as part of their recovery strategies from the pandemic. Such ways of working will encompass a variety of approaches, for example: advocacy, befriending, counselling, and organising social activities. These types of support have become essential in the current crisis and need to be strengthened over the longer-term. However, given the extent of the crisis affecting communities, a broader range of activities at a neighbourhood level should be encouraged, including: providing food co-ops, home repair services, financial advice, and protecting people from various forms of abuse.

Challenging discrimination: Coronavirus is disproportionally affecting groups based on age, ethnicity, gender, disability, and sexual orientation. Continued social distancing is likely to reinforce ageism and age-based divisions within communities. The number of deaths (direct and indirect) in care homes from COVID-19, and the delay in recognising the extent of the disaster, illustrates the extent of the crisis in social attitudes towards ageing. Older people are increasingly presented as a burden in relation to the economy, pensions and social care – an issue which needs to be tackled at all levels of society.

We support the call from the British Society of Gerontology and the Centre for Ageing Better for a fundamental culture shift to challenge negative attitudes towards older people. Given the risk for greater age segregation occurring as a result of COVID-19, it is essential to foster contact between generations, challenge ageist stereotypes, and highlight the diversity of experiences in later life. We also urge the government to work with national and local equalities organisations to support older people who are facing intersecting pressures relating to ageism, racism, and sexism.

Originally published 1 June 2020

What should transport and mobility responses be now and beyond?

Dr Ransford A. Acheampong

The measures we put in place around transport and mobility are critical to how we emerge from this pandemic and rebuild in the coming years. Dr Ransford A. Acheampong examines how to make transport safe as some of the most vulnerable groups are returning to work, and shows that active travel is essential to reducing pressure on public transport and should become central to our transport and mobility futures.

Low-wage vulnerable workers, who cannot work from home and are at greater risk of catching the virus, tend to depend on public transport for commuting purposes.

Social distancing can be achieved with walking and cycling, making a mass cycling culture critical to our collective health, well-being and resilience now and in the future.

There is a unique opportunity to learn lessons and to invent new futures for towns and cities, including the way we travel.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought major disruptions to social life, work and the way we travel. There is already evidence pointing to serious ramifications for the global economy. In the UK, after months of lockdown to protect public health, the government is desperate to have the wheels of the economy turning again. The lockdown is gradually being eased since mid-May, and people are being asked to return to work.

It is clear that the measures we put in place around transport and mobility will be critical to how we emerge from this pandemic and rebuild in the coming years. This is particularly important in the face of real concerns that the government’s responses regarding transport and mobility, in the short to medium term, will have serious implications on whether or not there is a second wave of infection of the virus.

In the months of the lockdown, we have witnessed an overall decreasing trend in movement by different modes, including public transport, car-based transport and even walking and cycling. As people return to work, we are also witnessing a gradual increase in traffic on our roads and in the use of public transit in our major towns and cities, such as London. One of the key questions we now face is how to make transport safe for people who are returning to work?

Figure 3. Changes in transport habits across the lockdown period saw rail and tube experience massive drops in footfall

In response to this, the UK government has issued transport and travel guidelines, which essentially advices commuters to avoid public transport, if they can, and instead drive, cycle or walk. What could the likely impact of these transport measures be?

Some of the most vulnerable groups are returning to work

Firstly, we know from the evolving evidence that while COVID-19 poses serious risks to the population as a whole, people from ethnic minority backgrounds are some of the most affected groups in the UK. While factors such as prior health status and underlying health conditions have been attributed, it is possible that the differential levels of risk and vulnerability are partly the result of the occupations that people are engaged in. It appears that people in low-wage work across different sectors of the economy are at greater risk of catching the virus, partly because of the nature of their work. These low-wage vulnerable workers, who cannot work from home, also tend to depend on public transport for commuting purposes.

On the one hand, UK Transport Secretary Grant Shapps has indicated that it is a ‘civic duty’ for people to avoid public transport. On the other hand, we know that public transport is essential for most people to access opportunities, including going to work. Indeed, in 2018/19, some 4.8 billion journeys were made by people using their local buses in Britain, constituting about 58% of all public transport journeys. In London, 27% of workers drive to work, with many of the remaining workers depending on other modes, including public transport. This means that some of the most vulnerable population who are now returning to work, do need public transport to be able to do so. Consequently, there is real risk that people will continue to use public transport in large numbers despite government advice, potentially risking their health and that of the general population.

Making public transport safe and reducing travel-related transmissions

So, how do we ensure that transportation measures being taken actually protect public health?

Increase public transport service frequency. The UK government’s latest safer travel guidelines indicate that there is going to be reduced capacity of public transport services. However, in order to avoid overcrowding on public transport, as we are starting to see on tubes and buses in London and elsewhere, it is crucial that capacity is increased by increasing the frequency of services, especially during peak-hours of travel.

Make public transport faster. Again, the UK government’s safer travel guidelines signals that travel may take longer than normal on some routes. Longer travel time, added to social distancing not being possible as a result of overcrowding, could increase the time that passengers come into contact on public transport, thereby increasing risk of travel-related transmission of the virus. As more people return to work driving, congestion could return, and travel delays on public transport in our major towns and cities could return to the pre-pandemic levels or even worsen. Thus, in the short-to-medium term, it would make sense to reallocate more road space by creating new dedicated bus lanes with the aim to making service more frequent and faster.

Ensure social distancing on public transport and at stations. Basic measures such as reducing occupancy on public transport, marking seats where passengers can sit and controlling passenger flow in stations could go a long way to making public transport use safe and protecting the vulnerable populations who depend on it. Obviously, doing so will amount to reducing capacity, but this can be offset by increasing the frequency and speed of services, such that at regular intervals, more buses, tubes and trams are available for people to board.

Active transport—are more people going to cycle?

The benefits of cycling and walking are obvious, and it does not come as a surprise that the safer travel guidelines encourage more people to do so as they return to work. From the UK government’s position, as reflected in the travel guidelines, walking and cycling are essential to reducing pressure on public transport. Social distancing can be achieved with walking and cycling, with added benefits to the environment and the health of those who do it. The government’s plans for cycling in particular, and some of the actions backing those plans, including the ‘creation of a £2 billion package to create a new era for cycling and walking’, are steps in the right direction and are welcome. However, we need to be careful and even cautiously optimistic about what levels of cycling could actually be realised in the short-to-medium term.

Compared to countries such as The Netherlands and Norway, the UK is a low-cycling country. Nationally, cycling constitutes just about 1% of total trip mileage. In London, where cycling has increased significantly in recent years, less than 3% of all trips were undertaken using the bike pre-COVID19 pandemic. Females and older adults as well as ethnic minorities and low-income groups are under-represented in the number of people who cycle.

A plausible scenario for the UK is that car use will return to pre-pandemic levels or even increase as people avoid public transport. This could make cycling seem unsafe, especially for those that the government is intending to encourage to change their behaviours. If commuters do not drive and cannot cycle, then they have no option but to use public transport. Thus, in the short-to-medium term, as more people return to work, the focus should be on making public transport safer, faster and reliable, by implementing the measures already outlined in this article.

Beyond the pandemic—inventing our transport and mobility futures

In the coming months and years, society and economies will recover from the devastating impacts of COVID-19. There is a unique opportunity to learn lessons and to invent new futures for towns and cities, including the way we travel. Sustained, long-term investment in cycling, walking and public transport should be central in these futures.

As this pandemic has shown, a mass cycling culture, is critical to our collective health, well-being and resilience now and in the future. There is the need for policy to help remove barriers to cycling among under-represented groups, to create inclusive transport futures. In the unfortunate event of another pandemic, we can be sure that the investments we make in cycling and walking, in particular, will yield dividend in aiding our rapid recovery.

Above all, making transport sustainable will be crucial to reversing climate change and averting potential cataclysmic impacts now and in the future.

Originally published 3 June 2020

Building back a gender balanced better – devolution, growth and equalities

Professor Francesca Gains

As the initial period of lockdown is slowly relaxed, the policy agenda in all parts of the UK is turning to examine recovery from the economic devastation caused by the pandemic. Policymakers in our major city regions are considering how to start up and stimulate economic activity where safe to do so; help firms and employers transition to new ways of working; and deal with the inevitable growth in unemployment that will flow from recession. Here, Francesca Gains, Professor of Public Policy, discusses the need to consider gender equality when making decisions on how to build back better.

As well as these urgent economic agendas, there is also a desire to learn from the disruption of the pandemic – to think about how to ‘build back better’. To capitalise on the social and environmental benefits that lockdown revealed: strong community and neighbourly support, less traffic and pollution, less time commuting and the potential for more time for parents to share responsibility for childcare.

Fairness and equalities

The lockdown also highlighted the following issues around fairness and equalities, moving these agendas to the top of political and public awareness and debate:

· The higher risks of being affected by the serious symptoms of COVID-19 faced by men and Black and minority ethnic (BAME) communities;

· The concern for (predominantly) women and children living with domestic violence;

· The higher risks of exposure to infection faced by key workers in certain occupations, such as low paid and mainly female care workers;

· The imbalanced unpaid care done within households by fathers and mothers;

· That women are more likely to be in a job that can be done from home with consequent risks to their productivity due to increased childcare and homework duties;

· The greater risks of redundancy following furlough in sectors like retail and hospitality which have a largely female workforce.

This awareness provides a rare opportunity to get equalities policymaking on the agenda. Too often equalities is side-lined unless an economic case can be made. The current circumstances provide this strong economic incentive to build back better especially in devolved areas. Combined authorities headed by a mayor have a vital role in stimulating and coordinating economic growth through their local industrial strategies, skills investment and employment support as well as through enabling integrated public transport. Mayors can be a vital voice for the city regions, working with local authorities, anchor institutions and stakeholders helping to coordinate, target and stimulate growth. But a focus on equalities data on employment will be important in understanding how to target policy to get productivity gains.

Gender and the loss of productivity in the labour market

On Gender, produced for the Greater Manchester Combined Authority Women’s Voices Task Group in 2019, illustrates how the labour market is occupationally segregated, with women being hugely over-represented in low-paid, insecure caring and administrative sectors, leisure, and retail; and men over represented in the manufacturing, construction, engineering, technical and managerial sectors. This picture is replicated in all combined authorities.

Figure 4. The occupational disparities within the female labour market across Combined Authorities are stark.

When the gender differences in labour market participation are examined in Greater Manchester and elsewhere it is clear how women get squeezed out of full-time employment during the years of childrearing and childcare. Analysis shows that the risk of economic inactivity is an intersectional one where BAME women face an even higher likelihood of part-time working or unemployment. A lack of affordable childcare and problems with transport are seen as vital in helping women balance work and care.

The evidence in On Gender shows how the gender differences in employment, occupation and labour market participation are exacerbated during child-bearing years and feed through into gender pay gaps; and greater income insecurity in older age for women with potential consequences for wellbeing and the need for social care.

Having a gendered lens to policymaking is essential to understand how these inequalities build over the lifecycle and how to tackle these issues. For example:

· To address gendered educational choices and build gender targets into skills strategies to support construction and digital skills pathways to encourage girls and to enter occupational sectors where they are underrepresented;

· To work with employers in sectors where future innovation and growth is expected, such as the IT sector, to tackle working practices and expectations which make progression at work difficult to combine with family life;

· To promote the adoption of the voluntary living wage for low-paid workers such as those in the care sector;

· To support the development of vital childcare and transport infrastructure to help skilled female workers manage work and care.

Ensuring building back better involves building back fairer

As the agenda to ‘build back better’ develops, understanding the data on gender and inequalities in the new devolved mayoral authorities will be even more vital on economic grounds to avoid further entrenching occupational segregation. Without deliberate action to ameliorate job losses in sectors where women predominate, realise productivity gains and unlock talent by keeping women in the workforce the impact of the pandemic risks exacerbating gender inequalities.

On social and fairness grounds, Greater Manchester with its health and social care devolution responsibilities will need to work with Government, local authorities and providers to address the problem of social care funding. The vital work provided by low paid and precarious social care workers should be valued. Addressing precarious work is not just important for fairness, but also will support the foundational economy, ensuring the underpinning exchange of goods and services within very local areas.

And the role of combined authorities in supporting (when safe to do so) better public transport, walking and cycling will help achieve some of the environmental potential lockdown revealed. Supporting changing working patterns with less commuting and more working from home can be harnessed to support a balance of work and care in households helping fathers to be more involved in child care.

Now more than ever combined authorities are absolutely critical in tackling some of these pressing, cross-cutting agendas on economic, social and fairness grounds. With the budgets and decisions devolved to combined authorities the equalities agenda is key to helping with recovery.

Originally published 11 June 2020

Can shipping emissions be kept in check in a post-COVID future?

Simon Bullock

The shipping sector is playing a vital role in the COVID-19 pandemic, keeping Britain supplied with everything from pasta to PPE. But what role does it need to play in another great crisis – preventing catastrophic climate change? Here, Simon Bullock from the Tyndall Centre, Manchester, looks at what needs to be done in order to keep shipping emissions below the 1.5 degrees Paris Climate Agreement.

Ships typically emit less carbon dioxide (CO2) per tonne of freight than lorries or planes. But the global impact of shipping is still huge: if it were a country, it would be the 6th highest emitter in the world. So what needs to be done?

New research from the Tyndall Centre explores this issue for shipping through the concept of “committed emissions”. Committed emissions are those emissions we can expect to see in years to come from existing infrastructure – in this case, existing ships that will continue to emit CO2 across their 30-year lifetime.

Our research considers ships travelling to and from the EU in 2018 – how much CO2 they are emitting, and how long they are likely to stay in service. The committed emissions just from these existing ships exceeds the amount of CO2 EU shipping is allowed to emit overall if it is to make a fair contribution to the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees. Because ships have average lifetimes pushing three decades, it is existing ships, not new ships, that will be responsible for most of shipping’s future CO2 emissions. This is in contrast to the road transport sector, where there are shorter product lifetimes, and a much faster turn-over of the vehicle fleet.

But, there is hope. There are many ways in which emissions from existing ships can be cut: slower speeds, fitting modern sails, using green electricity when in port, retrofitting vessels to be more energy efficient, greater use of hybrid vessels using batteries, and retrofitting vessels to use zero-carbon fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen.

Our research shows that if new vessels are able to run on zero-carbon fuels from 2030, then a strong suite of policies targeting existing vessels – on speed, operational efficiencies, blended fuels and zero-carbon fuel retrofits – could keep shipping’s emissions within the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degree carbon budget. But only if this action to retrofit the fleet happens quickly.

What needs to happen next?

First, the International Maritime Organisations (IMO) current target of at least 50% cuts in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 needs to be significantly tightened to be compatible with the Paris 1.5 degrees goal. Our research indicates that keeping within 1.5 carbon budgets would need shipping CO2 emissions to fall to net-zero by 2040.

Second, the IMO’s policy focus is predominantly on measures for new ships, such as the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) energy efficiency policy, which sets emission levels per tonne km for new ships. While this and at-scale deployment of zero-emission fuels and ships by 2030 are both essential, it is critical that the IMO focusses on measures that cut emissions from existing ships as well, as existing ships will produce the bulk of future emissions. “Slow steaming” is one of the best short-term measures to cut energy use and emissions; ship operators still widely practice this since the financial crash, to cut fuel costs. This has cut the CO2 intensity of ships by 30% since 2008. Further savings are possible still but require some form of international policy mechanism. One problem is that progress at the IMO is mired in complex wrangles over policy design, with reluctance to make any measure mandatory. Breaking the international impasse on progress on slower-speeds is a priority.

Third, the research shows wide variety in the lifetimes and committed emissions profiles of different classes of ships, implying that targeted policies are needed. Refrigerated cargo ships have an average of 9 years likely future life, whereas for passenger ships it is 29 years. For ships and ship types with shorter remaining life, it’s hard for ship-owners to make a strong economic case for actions on their own, so the successful uptake of emission reduction measures requires action from policy makers, such as regulating on speed, setting standards on retro-fitting to improve efficiency, or market-based mechanisms that impact on fuel price.

Efficiency improvements on new ships won’t be enough

The committed emissions from ships are significant, yet a combination of policies on very low-carbon ships from 2030, combined with speed and operational measures from the early 2020s, could keep shipping within a Paris-compatible carbon budget. However, any delay to appropriate policy implementation would mean additional measures, including demand-side or early scrappage interventions, are needed to meet the Paris climate goals.

The time left to deliver on what is dictated by the global Paris Agreement is too short to rely on measures that predominantly focus on improving the efficiency of new ships. Policy makers should include a focus on measures that clearly target the existing fleet.

Originally published 15 June 2020

Recognising the value and significance of cleaning work in a context of crisis

Professor Miguel Martinez Lucio and Dr Jo McBride

Professor Miguel Martínez Lucio of the Work and Equalities Institute and the Alliance Manchester Business School and Dr Jo McBride of Durham University discuss the question of how we have failed to value the work and importance of those in the area of cleaning and hygiene-related employment more generally. The need now is to consider how such workers are engaged with and supported through a greater framework, with respect and dignity being paramount. This is essential if we are to overcome the challenges of ongoing crises such as that of the current pandemic.

Even before the introduction of social distancing at workplaces, many cleaning workers found they were working more in isolation (due to job cuts and less supervision). We interviewed cleaners working across four different public sector organisations to learn about their experiences in the workplace. Alongside working more in isolation, many cleaners are being left to decide what they feel is a work priority, indicating that they are taking on more of a decision-making role in the workplace. This sense of increasing discretion could be perceived, albeit superficially, as a further complexity of the work. This undermines the use of the term ‘unskilled’. Others began to draw out a growing sense of awareness of the negative context of the environment and the way it impacts on their work and decision-making.

The context of safety and violence in many aspects of cleaning

Due to the growing isolation of their work, many of the cleaners we interviewed felt they were also at greater risk in terms of danger, fear, and violent threats. Cleaners who worked alone explained how they had experienced more direct forms of threats, particularly when working in public spaces. Levels of physical abuse were significant. Many of these workers perceived recent cuts to their operations as a contributory reason for an increase in negativity by the public and were having to respond to this in various ways. One domestic refuse collector told us: “Oh, you get abuse all the time, like. I’ve had stuff thrown at me, bags and everything. They come out and swear and shout at you.”

Austerity and cutbacks

Street cleaners especially have needed greater discretion in their job, not only in threatening or violent situations, but also when facing hazards to their health in the work they undertake, such as when handling discarded, dirty needles on the streets. Cleaners have to also help each other develop their knowledge of challenging areas of work and how to respond without the necessary materials. Their roles are expanding to the point where they include managerial dimensions in terms of decision-making and using greater levels of discretion in terms of thinking through the consequences of actions. It is increasingly clear for the street cleaner to be given more responsibility of supervising another worker yet for this not to be valued remuneratively or by management. These are administrative features of their work which do not actually get recognised.

Stigma and the feeling of being valued

One of the challenges facing cleaners in recent years is the stigma attached to the job, as they are seen as unskilled and low paid. These concepts reinforce a sense of worthlessness – and that the job being done is ‘unimportant’.

In terms of stigma, and its related factors of dirty work, unpleasant work and risk, internal cleaners in our study thus received negative social perceptions of their work but also of the whole purpose of it. It is not just that the person doing the job is undervalued, but that the purpose of the job and its significance is simply not fully understood. This has a massive impact in terms of the way the economy is misunderstood and the way certain core activities that are important to sustain it are undermined. In stigmatising cleaners, the whole question of hygiene and health is undermined and thus is underinvested.

This lack of appreciation and even of the recognition of new challenges of these jobs also extended to other workers in the study. These were in relation to external cleaners, some of whom demonstrated that, despite verbal abuse and a lack of respect from some members of the public, they still had a sense of feeling dignified despite others’ negative perception of their work. Stigmatising workers and seeing it as peripheral work means that the core purpose and value of that sector is undermined. This has been happening for some time and has had a major knock-on effect on the way recruitment, development and quality within the economy is undermined within its very foundations.

Yet the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced a ‘Clap for Carers’ campaign of public appreciation for workers, involving some in our study. This demonstrates a mutual social perception of the value of much of this work and there is already a re-evaluation of such work in the public discourse.

Rethinking the way we envisage work and employment

First, the value of work has to be economically and symbolically supported in a more effective manner. The way we see the economy in skewed terms and the way we envisage support workers such as cleaners has curious knock-on effects. When there is a moment of crisis and work such as cleaning is deemed suddenly to be essential, we find that these subsectors are literally unable to respond to the challenge at hand due to their demoralised state or limited support in material terms.

Second, the need to recruit, retrain, upskill and retain such workers must be pushed into the centre of the political discussion. The lack of resourcing and the aggressive, and dysfunctional, management cultures that cleaners face prevents workers from pursuing a balanced and more effective approach to their work. This has led to immense fragmentation brought on by ongoing subcontracting and performance management which is not concerned with long-term development.

Third, the very way we think of ‘unskilled’ work needs to be challenged. Even key employer organisations within the cleaning sector have argued for decades that there is a need to not just value but professionalise the work and to remove the stigma of it being unskilled. The importance of health and hygiene is an important feature of the welfare interventions of the state. The need to recast our personal and political mindsets to include the voice and concerns of bodies of workers such as cleaning workers will be a challenge for future policymakers. It is also a cultural challenge in a society where the construction and maintenance of our infrastructure has played a secondary role compared to its commercialisation.

Millions of these frontline staff, now viewed as key workers, have been keeping the country running while facing risks to their own and their families’ health. The fact that they are ‘keeping the country running’ again undermines the persistent use of the term ‘unskilled’ with regards to this work. Indeed, this work is currently being recognised and valued across our communities in a way that has not been the case for some time. We therefore need to ensure that this continues to be recognised as valuable and meaningful work.

Originally published 10 June 2020

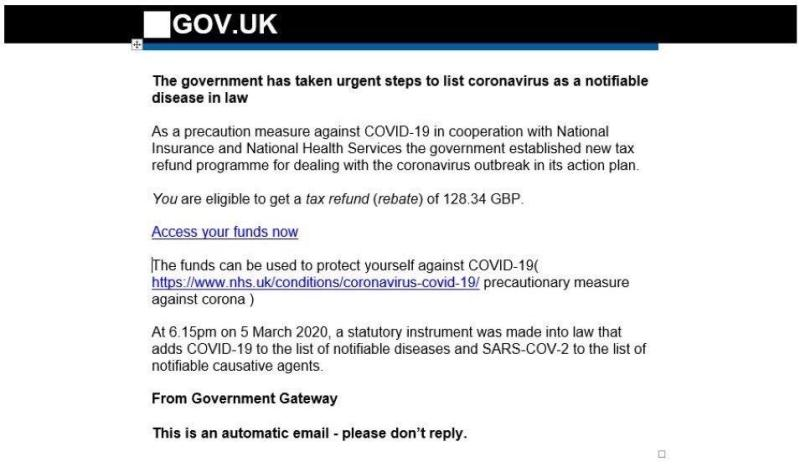

A tale of cities: Local diasporas hold a key to strengthening international outreach

Professor Yaron Matras

The publication of Government guidance on social distancing saw a delay between the release of the English language version and the guidance being provided in different languages. Professor Yaron Matras examines this disparity and suggests a new policy to prevent a similar issue arising in the future.

Amidst the intensity of instructing the public on how to prevent the spread of COVID-19, authorities in the UK have been slow in issuing guidance notes in languages other than English. The matter was raised by Labour MP Afzal Khan, whose Manchester-Gorton constituency is one of the country’s most linguistically diverse. Speaking in the House of Commons on 11 March 2020, he called on the Government to disseminate information in community languages. On 13 March, Doctors of the World UK published translations of NHS information leaflets into 44 languages; at a similar time, the Manchester charity Europia produced video advice in various European languages.

However, it wasn’t until late March that Public Health England added guidance on social distancing for vulnerable people in a number of languages. Meanwhile, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Councils published video information in 31 different languages, while Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham were among several local authorities to provide web links to the Doctors of the World translations.

The official UK Government COVID-19 information leaflet was finally published in a small number of languages on 7 April.

A more consistent approach

Authorities in the UK usually translate in order to ensure accessibility of services, or else as a way of regulating behaviour. They target those that are expected to be most liable to violate the rules: leaflets on forced marriage are disseminated in Arabic, Somali and Urdu, for example, while information on angling restrictions appears in Lithuanian, Latvian and Polish. But with COVID-19, the prospect that residents with a low level of English might become carriers of the disease poses a potential risk not just to them but to the entire population. If the UK Government had a domestic language policy in place, the translation of vital information could have been more efficient and consistent. In the absence of such macro-level policy, gaps are currently being filled in a somewhat random way by charities and local authorities.

Discourses around language policy

Over the past few years, especially since the EU referendum in 2016, the public discourse around language policy, to which many researchers have been key contributors, has seen two main strands of argumentation. The first is concerned with counteracting the decline in enrolment in traditional Modern Language courses (like French and German) at secondary schools and higher education. It calls on the government to recognise language skills as a valuable asset to protect British interests abroad, like security and trade. It sees national government agencies as the primary deliverers of this agenda. Some scholars frame it as linked to the mission statement of New Area Studies, seen as the intellectual arm of foreign intelligence gathering and ‘soft power’. Others have tried to capitalise directly on Brexit, cynically arguing that the imminent ‘departure’ of residents who are EU citizens will open up gaps in industries, to be filled by ‘homegrown’ workforce with language skills.

An alternative strand is concerned with language policy as a social justice agenda to promote equality in the domestic arena. It points to the rising uptake of language courses, particularly Arabic and Chinese, as heritage languages in non-statutory education such as supplementary schools, and recognises the importance of cities and local government, and of the intellectual concept of Locality to support heritage language speakers in creating local brands of ‘global diasporas’. In May 2019, Multilingual Manchester sponsored an open event, calling for the formation of a Multilingual Cities Movement that would bring together stakeholders from different sectors, uniting around the realisation that while many nation-states now promote linguistic sameness in an exclusionary way, cities are usually places where languages meet and linguistic plurality and difference are appreciated and celebrated.

Cities have the potential to forge international links. Diaspora communities within cities can play a pivotal role in that process. Global diasporas of today are not temporary emigrants waiting to return to their homelands, but active contributors to global networks of culture and trade. While maintaining links with co-ethnics abroad, they are also engaged in local practices of plurality. If they are allowed to thrive and cultivate their heritage languages, then the localities in which they are settled will be in a better position to be players on the world stage.

A domestic language policy

A coordinated and consistent domestic language policy must firstly acknowledge the UK as a multilingual society. It should take steps to dismantle the hierarchy that currently guides language teaching and which favours the languages of historical imperial European powers. It should recognise the value of heritage languages as skills and encourage the teaching of heritage languages in statutory and higher education, but also support community-based language learning that takes place in the country’s hundreds of supplementary schools. That will also offer a pathway to empower the second and third generations of immigrant background to act as transnational diaspora communities that can build bridges with counterparts in other countries – links that can strengthen diplomacy, investment, and cultural enrichment.

In addition to supporting heritage and skills, a domestic language policy should take steps to regulate the sector of Public Service Interpreting and Translation to ensure high-quality access to services to those with insufficient English language skills.

It also requires modification of key tools to gather accurate data on language use and language skills. For example, currently, the Census asks respondents to indicate their ‘main language’ other than English, but the concept of ‘main’ is vague, and respondents can only choose one single option. Instead, we should be asking about languages that are used in the home, as well as additional language skills. An effort needs to be made to change the public narrative on languages. Last year Boris Johnson, then still candidate for the Tory leadership, demanded that all UK residents should adopt English as their “first language”. We need to move away from such notions of one-sided ‘integration’. Instead, policy should encourage people to maintain language skills and cultural identity, and recognise that multiple identities and multiple languages are an asset for individuals and the country as a whole.

Cities can be active contributors to a new vision of a domestic language policy. A model example is Manchester’s commitment to a City Language Strategy that brings together the contributions of a variety of organisations in the public and community sectors. Strengthening diaspora communities can help them forge city-to-city links worldwide. Policy must ensure that community language needs are met consistently and not left to improvisation in times of crisis.

Originally published 5 May 2020

Build in haste, repent at leisure? Post-pandemic planning at the precipice

Professor Iain White, Professor Graham Haughton and Dr Nuno Pinto

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to discussions on what shape planning should take post-crisis. Here, Prof Iain White, Prof Graham Haughton, and Dr Nuno Pinto outline how current regulations have exacerbated difficulties for some people in lockdown, discuss how opportunistic developers or politicians may seek to hijack the policy responses, and suggest solutions to ensure the post-pandemic recovery is beneficial for all.

A wide-ranging discussion on the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic by city mayors, academics, and others, has evoked new ideas on how we live and move, and on how to transition economies to be greener and cleaner. Despite such good intentions, as the dust settles, we run the risk of returning to ‘business as usual’ and we are already seeing much new thinking side-lined, alongside a reversion to familiar narratives of ‘speed’ or ‘red-tape’. We must be cautious about altering the planning system so it can do the wrong thing more efficiently.

The cost of fast-tracking infrastructure

Under pressure for quick results, there are signs that some governments seek to short-circuit the planning system in order to expedite development. For instance, the mooted ‘shovel-ready’ infrastructure stimulus in New Zealand aims to create a fast-track process, where politicians select projects and there is no opportunity for citizen involvement. Significantly, the Minister in charge said that there should be a high level of certainty that consent is given. Meanwhile, Australia’s version of ‘fast-tracking infrastructure’ sees a call not just to cut ‘red-tape’ but ‘green-tape’ too—that is, environmental regulations. In the UK, the Transport Secretary recently used the term ‘bureaucratic bindweed’ to describe rules in the current system that presumably need to be eliminated.

During the current pandemic, English local authorities were initially forced to abandon their planning committees, instead giving greater powers to officials, sometimes aided by senior local politicians, to decide on major, occasionally contentious, projects. Requirements to publicise site notices have been relaxed in England, while the Housing Secretary has announced that instead of traditional methods, local councils and developers can use social media to publicise applications to ‘unblock’ planning. This is bad news for those without social media or access to technology or data, discriminating particularly against the elderly and the most vulnerable. While some local authorities in England have now adopted virtual planning committees, many have been slow to introduce them.

Under these relaxed measures, opportunistic developers may have been emboldened by relaxed planning requirements to bring forward proposals that are likely to be locally contested, hoping this might improve their chances of slipping projects through.

We structure our discussion about improving the processes of planning under three headings: better planning before, during, and after future pandemics.

Better planning anticipating pandemics

Having now experienced social distancing and lockdown, and with the prospect of a pandemic a recurring possibility, planners need to prioritise actions that better prepare for the implications. It is clear we need better provision of both private and public space. Homes need to be built to higher standards. Under current English regulations – as a recent case in Watford revealed – it is possible to build homes without windows, a decision upheld by the planning inspectorate, against the objections of local planners and politicians. Imagine an elderly or vulnerable resident being locked-down inside such a development.

Fortunately, the considerable public outcry, media attention and political opposition appears to have seen the developer reconsider the scheme. This only goes to show the importance of proper local scrutiny of development proposals. The problem here is that the English planning system no longer does this in all cases, and fast-tracking may give more power to developers. Rather than give away more permitted development rights, we should be looking to limit them, restoring local democratic scrutiny and the rights of local residents and citizens.

Better planning during pandemics