World Health Day 2021

The University of Manchester

Our research

At The University of Manchester, our experts are passionate about equality and finding answers to some of the world’s toughest challenges. That’s why our multidisciplinary research is at the forefront of innovation.

Through a series of health-related case studies and opinion pieces, some of our experts tell us how their research has real-world impact and is helping to improve people’s lives.

A wake-up call on inequality

Professor Bridget Bryne

The pandemic shone a light on many forms of inequality and discrimination. As we plan society’s recovery, Bridget Byrne, Director of the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE), highlights the lessons that must be learned.

One of the lessons of the pandemic is that racism and racial inequality kill. The evidence for this was already there, but the impact of the virus and lockdown has brought the tragic impacts of discrimination into sharper focus and made it even more urgent to address the root causes.

However, amidst this tragedy have been two perhaps unexpected and potentially positive effects of the pandemic. The first is an unprecedented recognition by policymakers, politicians and the media that COVID-19 has hit some groups disproportionately. In the context of the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd in the US, this has led some major institutions to begin the process of reckoning with racism and discrimination.

The second is a change in the public’s understanding of which jobs matter, and who is doing those jobs. As the posters went up in support of NHS and other key workers, the knowledge that those fulfilling the most crucial jobs in our society were often the most poorly paid has hopefully hit home. We have a new respect and gratitude for shopkeepers, nurses and taxi drivers who carried on working despite the risks.

These jobs are disproportionally done by people from racialised backgrounds and this is part of the explanation for their vulnerability to the virus, alongside factors such as housing, insecure employment and other forms of deprivation which increased risk and place a strain on health.

However, if we are to ensure the post-pandemic recovery reflects the need to address ethnic inequalities, we must have a more in-depth understanding of the impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on racialised and religious minorities. There remains a danger that we recognise that ethnicity is a risk factor for severe COVID-19, but then fail to address the underlying causes and wider impact of the pandemic on unequal life chances.

That’s why UK Research and Innovation’s funding for new studies into COVID-19 and ethnic minority groups is particularly welcome. CoDE is conducting a survey of ethnic and religious minority people’s experience of the pandemic and lockdowns so that we can have a clear picture of which ethnic groups have been most severely affected, with particular attention paid to gender, age, religion and region. It will examine people’s experiences of racism, encounters with the police, as well as the impact of the pandemic on employment, finances and mental and physical health.

In other projects, in-depth interviews will be used to examine individual experiences, including of older people, those working in the creative and cultural industries and hospitality sectors, as well as forms of community response to trauma and activism around rights.

The Black Lives Matter protests over the summer, alongside the recognition of the uneven impact of the pandemic, have given a new urgency to achieving a more just country. Crucially, we need to understand what the government, the NHS, employers, schools, colleges and universities need to do to make a step change in measures to address discrimination and inequality.

We’ve had a wake-up call on racial discrimination and inequality: we need to fully understand how it works and who it effects in order to stop it.

Take part in the survey: uom.link/xyz https://www.ethnicity.ac.uk/research/projects/evens/

Meet the researcher

Professor Bridget Byrne is a senior lecturer in sociology at The University of Manchester and director of the Centre on the Dynamics of Ethnicity and Inequality (CoDE).

Inequalities in ageing: health disadvantages amongst ethnic minority groups

Dr Ruth Watkinson and Dr Alex Turner

Both the direct and indirect consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have hit those from poorer areas and ethnic minority groups hardest. These devastating impacts have come on top of long-standing health inequalities, which had already been exacerbated by years of austerity. In February 2020, a damning report into health inequalities in England found that the previous trend of steady increases in life expectancy was already faltering, and that life expectancy in the poorest communities was actually falling for the first time.

More shocking still, we simply do not know whether or how life expectancy trends have differed between ethnic groups over the same period. There are no estimates available because ethnicity data is not recorded across many administrative systems and there is poor representation of ethnic minority groups in national datasets. This negligence is a form of institutional racism, and allows health inequalities by ethnicity to largely go unmonitored and therefore unchecked.

What does our study show?

Our recent study used the national GP patient survey to describe ethnic heath inequalities amongst older adults (aged 55 plus), an age group that is becoming increasingly ethnically diverse. As populations are ageing and more people are living for many years with multiple chronic health conditions, supporting healthy ageing has become an important focus of healthcare and health research. Health inequalities amongst older adults are a particular concern, as the effects of repeated disadvantage accumulate over the course of life, thereby widening inequalities.

Drawing on responses from over 150,000 older adults who self-identified as belonging to ethnic minority groups (as well as over 1.2 million who identified as White British), we found wide inequalities in health-related quality of life, a measure of day-to-day physical and mental health. There were particularly striking disadvantages for some groups; the average health of 60 year olds belonging to Gypsy or Irish Traveller, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Arab groups was similar to that of an average 80 year old.

Importantly, we found wide variation in outcomes between different ethnic minority groups, including those that are often combined in statistical analysis. For example, considering Asian ethnic groups, health-related quality of life was substantially worse amongst Bangladeshi and Pakistani older adults than amongst those of Indian, Chinese, or other Asian ethnicities. This highlights the importance of collecting detailed ethnicity data and including sample sizes that allow analysis of each group individually rather than using broader and potentially unhelpful groupings such as ‘Asian’ or ‘BAME’, which can mask inequalities.

Looking at what might drive these inequalities, we found people from most ethnic minority groups were more likely to have more long term health conditions than their White British peers. With good treatment and support, health conditions don’t inevitably lead to declines in quality of life. However, we found people from ethnic minority groups tended to face additional disadvantages in the healthcare and support they received. Older adults from some ethnic minority groups were more likely to report poor experiences at their GP surgery. Similarly, those from almost all ethnic minority groups were much more likely to say they lacked confidence managing their own health and didn’t receive enough support from local services. These results suggest some NHS and other local services are failing to meet the needs of all individuals equally, adding to growing evidence of institutional racism.

Finally, consistent with many other reports and evidence of pervasive structural racism across British society, we found that older adults from almost all ethnic minority groups were much more likely to live in socially deprived neighbourhoods; further contributing to inequalities in health.

What policy changes are needed?

Over recent years, there have been many reports into discrimination and ethnic inequalities across settings from education and workplaces to the criminal justice system and public health. Each report makes recommendations but few have been meaningfully implemented. The recent Lawrence Report focused on the impacts of the pandemic on ethnic minority groups. It concluded that a wide-ranging national strategy to reduce health inequalities is urgently needed, and must be developed collaboratively with representatives from ethnic minority communities. The government needs to respond with clearly specified and ambitious targets, which must be backed up by legislation, ministerial accountability, and funding.

Progress and accountability will rely on better data, so this must also be a priority. Routine monitoring of ethnic inequalities in health and its determinants as part of performance measurement of local health systems should become commonplace, as has occurred for deprivation-related inequalities. Without this, the success of enacted policies will be difficult to judge.

Equity should be central to quality assessments of all health and wider local services. Where services are not working fairly, it will be important to understand why. Investment and community co-design will be needed to remove access barriers and ensure services are culturally and linguistically competent. As discussed in the recent BMJ special issue on racism in medicine, investment is also needed to improve medical education and increase unconscious bias and anti-racism training for medical staff.

While neither these problems nor solutions are new, there may be a real moment of opportunity to respond to the powerful activism of the Black Lives Matter movement, and to “build back fairer” in the wake of the pandemic.

Meet the researchers

Dr Ruth Watkinson is a research associate in the Health Organisation, Policy and Economics (HOPE) group at The University of Manchester. Her research focuses on health inequalities, in particular looking at inequalities between ethnic groups and socioeconomic groups.

Dr Alex Turner is a Presidential Research Fellow in Health Economics in the Health Organisation, Policy and Economics (HOPE) group at the University of Manchester. His research focuses on health inequalities, and the development and application of methods to evaluate large-scale changes in the organisation of hospital and child services.

Black mental health matters: Time to eradicate long-standing ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare

Jamal Alston, Dr Henna Lemetyinen, and Professor Dawn Edge

Health inequalities are unjust and preventable disparities in access to care, experience, and outcomes between different groups of people. At local, national, or global levels; inequalities in physical and mental healthcare are influenced by ‘social determinants’ such as age, socio-economic status, and ethnicity.

In the UK, individuals from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds experience ‘varied and pervasive’ inequalities in mental health and wellbeing. We use ‘BAME’ here due to its familiarity. However, we recognise and urge others to reflect on how agglomeration of vastly different experiences can obfuscate meaning. One of the most consistent UK research is elevated rates of schizophrenia and related psychoses among people of Black African and Caribbean backgrounds, including those of ‘Mixed’ heritage, compared with White British peers.

No single cause accounts for these differences. Comparative studies have not found similar rates of morbidity in Caribbean countries like Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad. Racism, discrimination, migration, social and economic disadvantage are among contributory risk factors. Additionally, Black people’s inferior care (eg disproportionate rates of death in service and detention under the Mental Health) has led many observers to conclude that mental healthcare in the UK is institutionally racist, a position endorsed by the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Tackling ethnically-based inequalities: ‘Too hard to do’?

Ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare appear intractable, despite a National Health Service (NHS) founded on the principle of equity and numerous policies and practice guidelines to tackle disparities. After several decades of such strategies, research indicates that Black people continue to be less likely than other ethnic groups to receive timely diagnosis, treatment, and support. Instead, their experiences of mental healthcare is characterised by negative care pathways, often involving the police, and more coercive forms of treatment such as forcible injection of psychotropic medication and being held in isolation.

Black and other UK ethnic minority service users rarely receive culturally-sensitive care. For instance, faith and spirituality (which can buffer symptoms of distress and support recovery) are too often regarded as “irrelevant, harmful, and pathological” by practitioners. People of African and Caribbean origin are also less likely to receive psychological therapies. Those who do, report that their lived experiences and explanations for their difficulties are rejected, nullified or reframed as evidence of illness – particularly when these involve racialisation. Perceptions of practitioners’ lack of empathy and/or cultural awareness have detrimental effects, reinforcing mistrust and increasing the likelihood of disengaging from services; thus further increasing inequalities in access to evidence-based care.

Although various organisational bodies, such as the Royal College of Psychiatrists and NHS England, recommend culturally-sensitive care, there currently exist no clear national guidelines or regulatory standards for what evidence-based culturally-sensitive care looks like or how it can be implemented and evaluated. Research findings on the role, implementation, and results of ‘cultural-competency training’ in UK healthcare settings are ambiguous. Addressing consequential gaps in service provision is essential to tackling mental health inequalities that relate to ‘race’ and other Protected Characteristics as defined under the Equality Act, 2010.

Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR): A way forward?

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) highlight the urgent need to develop evidence-based, culturally-informed talking therapies to bridge the treatment gap experienced by the UK’s minority ethnic populations.

In response, people diagnosed with schizophrenia (and related psychoses), their families, healthcare practitioners, and community members have collaborated with us to co-produce Culturally-adapted Family Intervention (CaFI). Originally piloted with Caribbean-origin families in Manchester in 2013-2017, aspects of the CaFI therapy designed to maximise its utility and acceptability with families and mental health professionals included culturally-informed explanations of mental health problems (such as religion and belief) and improving CaFI therapists’ cultural competency. Service users and carer participants in the pilot study endorsed CaFI’s cultural acceptability and therapists reported increased confidence and competence in working with families of Caribbean origin.

Subsequent to the successful pilot in Manchester, our team of national academics have secured £2.5 million of National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) funding to further refine and evaluate CaFI with people from Sub-Saharan African and Caribbean backgrounds. This involves evaluating CaFI’s clinical and cost-effectiveness in a randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Our research will also identify barriers to implementing the therapy across a number of mental health NHS Trusts in England and solutions to overcome them. We anticipate that ensuring service user and carers are integral to research design, delivery, and evaluation will lead to more holistic mental health care, which service users and their families find acceptable. Accordingly, our work strives to amplify African and Caribbean communities’ voices in informing CaFI therapy resource development, therapist training, research management and dissemination.

Through meaningful collaboration with service users, their families, and healthcare professionals, we are learning valuable lessons that we intend to share with the wider research community and mental health services. We hope that these insights will inform strategies for increasing the participation of BAME populations in clinical trials, as well as shape policy and commissioning decisions. Effectively tackling inequalities in mental healthcare provision and outcomes will enable us to confidently assert that ‘Black mental health matters’. This is especially pertinent in preparing to adequately address the potential mental health crisis during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Policy recommendations

We propose the following policy recommendations for tackling long-standing inequalities in mental healthcare experienced by Black and other UK minority ethnic groups in the UK.

- Cultural competency and inclusive service delivery should be standardised in healthcare practice and curricula across the NHS to ensure that diverse groups receive high-quality, holistic care.

It is imperative for healthcare professionals to challenge their assumptions in care delivery, which if unchecked, could inadvertently reinforce institutional practices that produce mental health inequalities. We must also develop diverse versus ‘one size fits all’ approaches; thereby promoting understanding of how factors such as membership of LGBTQ+ communities, age, and disabilities intersect with ‘race’/ethnicity to magnify inequalities.

Comprehensive, standardised, and evidence-based cultural competency training could enable healthcare professionals to work more effectively and confidently with diverse cultures and experiences. This includes enabling healthcare professionals both to understand how issues like racism detrimentally impact mental wellbeing and equipping them to maximise mental wellbeing and help-seeking for UK-minority people both within and outside the NHS. For example, even though spiritual wellbeing can be crucial for healing and recovery, it is often neglected in mental healthcare. In addition to providing more holistic care, working with faith leaders could help to reduce stigma and promote understanding and timely access to care. Representation of BAME people in key leadership roles in healthcare and policy must also be improved to better inform inclusive mental health provision.

- Monitoring and evaluation of UK mental health services by regulatory bodies must incorporate assessment of workforce capacity to deliver holistic care and service users’ rating of their experience.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the National Clinical Audit Programme should develop criteria to assess service user satisfaction, safety, and the availability of culturally-sensitive care against benchmarked regulatory standards. Patient satisfaction criteria alongside Workforce Race Equality Standards (WRES) should be used routinely to drive up Equality, Diversity & Inclusion (EDI) standards within services and should be mandatory components of statutory inspection reports and service rating. Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and Health and Wellbeing Boards should be held accountable for filling gaps in mental health provision for all people thus, ensuring that inequities are eradicated.

- Mental health services should actively work with service users, their families and community groups such as faith-based organisations at ‘a grassroots level’ to better understand their needs and co-produce solutions.

Collaboration of this kind provides opportunities for bi-directional learning about:

- culturally-based conceptualisations of mental health and how these might inform both hospital and community-based treatment

- developing and evaluating initiatives to dispel stigma about mental health

- more inclusive and novel public health education approaches to, for example, identifying and responding to early warning signs of poor mental wellbeing to facilitate more timely access to care and support

We believe that more effective partnership working will enable a plurality in service provision, which is necessary for optimising patient choice, for example, multiple entry points into specialist NHS mental health services. Meaningful engagement with diverse communities also fosters the potential for co-producing more culturally-informed psychosocial interventions by mobilising ‘citizen scientists’ and providing under-served communities with opportunities to become more actively involved in research.

Meet the researchers

Jamal Alston is a Research Assistant working at Greater Manchester Mental Health (GMMH) NHS Foundation Trust on the Culturally-adapted Family Intervention (CaFI) study. Jamal has research interests in reducing mental health inequalities through an intersectional approach.

Henna Lemetyinen is a Research Associate of the Culturally-adapted Family Intervention (CaFI) study. Henna works in the Research & Innovation department at Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (GMMH).

Dawn Edge is Professor of Mental Health and Inclusivity at The University of Manchester’s Division of Psychology and Mental Health, and the University's Academic Lead for Equality, Diversity & Inclusion (EDI) with a specific focus on race and students. Her research focuses on improving health outcomes and reducing inequalities in underserved populations.

Exploiting the link between Lynch syndrome and womb cancer

University researchers have used genetic testing to help increase the early detection of womb and bowel cancer, changing national policy and giving patients a better chance of survival.

Global problem: late detection of a silent killer

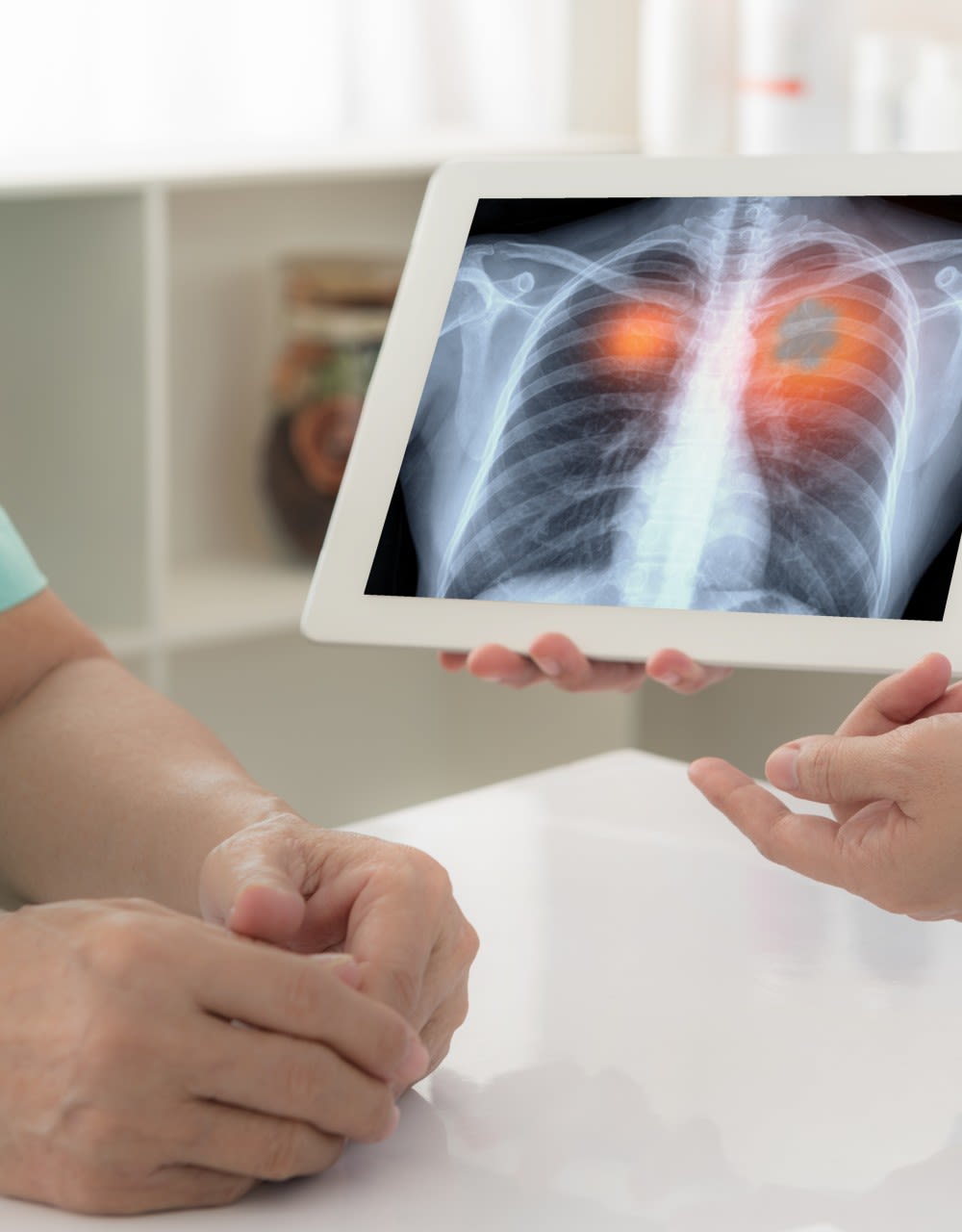

Lynch syndrome is a genetic condition that can significantly increase the risk of developing cancer, particularly endometrial (womb) and bowel (by up to 80% in the latter case).

Bowel cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the UK and particularly aggressive as detection generally happens at an advanced stage – earlier detection is needed to increase survival rates.

Alongside this, evidence has shown that for women with Lynch syndrome, developing womb cancer is an early indicator of their susceptibility to bowel cancer.

Manchester solution: saving lives through earlier detection

Researchers at The University of Manchester led the first study of its kind in the UK that tested women diagnosed with womb cancer for Lynch syndrome, confirming the link between the two.

By helping to identify those who are Lynch positive, patients and their families can undergo regular early detection testing for bowel and other cancers.

Shaping national policy

This research has now formed the basis for a national policy change on earlier screening and shown how testing all women with womb cancer for Lynch syndrome can then enable preventative or early screening tests for bowel cancer, which is traditionally difficult to detect.

Life-changing impacts

The University of Manchester’s research has helped to:

- confirm the link between Lynch syndrome and womb cancer, an important breakthrough that paves the way for increased testing and earlier diagnosis;

- successfully show that all women diagnosed with womb cancer should be tested for Lynch syndrome so that they and their families can find out whether this inherited condition has raised their cancer risk;

- secure an important change to diagnostic testing policy in England and Wales. NICE Diagnostic Guideline 42 now calls for every woman diagnosed with womb cancer to be tested for Lynch syndrome;

- provided the evidence for a policy that will identify more than 1,000 additional cases of Lynch syndrome every year, enabling screening and early cancer detection for hundreds of people.

Find out more

- Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health story: Driving changes in womb cancer detection

- Policy@Manchester's website: Lynch syndrome activity

Meet the researcher

Professor Emma Crosbie, Professor of Gynaecological Oncology.

Reducing the risk

Professor Gareth Evans is an international leader in cancer genetics, with a focus on neurofibromatosis and breast cancer. His research has led him to conclude that risk stratification offers the best way of targeting prevention and early detection (PED) approaches. Here, he outlines why Manchester is perfectly placed to lead on this outcome-changing approach.

I've become more involved with prevention and early detection of cancer because it's all very well identifying people's risks, but if you can't do anything about them then it's almost pointless. My research focuses on optimising our PED approach to cancer by calculating an individual's total cancer risk, regardless of family history.

My main focus has been risk identification for breast cancer, moving away from using family history as a risk tool and looking across all women in the general population to enable more targeted early detection and prevention strategies that will better balance the risks and benefits of population screening programmes.

Although my main focus was initially breast cancer through higher risk and moderate risk genes, I am now more involved in looking at common genetic variants called single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to produce something called a polygenic risk score.

We feel that this work is ready to be used to more accurately identify those at increased risk of other cancers, so that PED can be better targeted at those at the higher levels of risk. Potentially, those with low levels of risk can be reassured that they actually don't need screening, as screening might actually be more harmful than good for them.

Savings to the NHS

For me, the reasons why risk stratification is the way forward are multiple, not least because of the potential cost savings to the NHS. If you use risk stratification properly, you can increase screenings of those at higher levels of risk and reduce screenings of those at lower levels, making the actual cost neutral. Better targeting means you're hopefully picking up the cancers earlier, which means a cost saving as those women will require less treatment.

Similarly, identifying higher risk people helps identify those who would be eligible for medication prevention treatments such as the three NICE-approved drugs – Tamoxifen, Raloxifene and Anastrozole. Anastrozole went through a health economic assessment for breast cancer treatment and results showed that there would be a cost saving to the NHS. It only costs 4p a day to treat someone with Anastrozole, but you halve the number of breast cancer incidence - literally cutting in half how many women will get breast cancer. This is a potentially massive benefit to the NHS.

Additionally, the risk stratification, including the genetic element which is the most expensive part of process, only needs ever to be done once. You may need to do an assessment of the other risk factors, including mammographic density, on two or maybe three occasions.

Putting the machinery in place

The NHS moves very slowly, however, and there is much to be done. We need to persuade the national screening committee that risk stratification is the way forward because it will represent a huge change for risk assessment to be brought into the screening programme. In current screening processes, every woman is treated the same.

However, risk stratification is already being done for cervical cancer because it is now going to be different screening for those with Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) than those without the virus. Screening after the age of 50 is going to be relaxed for those that aren't HPV positive. So risk stratification is coming in, using the tools available.

There are some high risk screening programmes already taking place. Colonoscopy is being used to screen patients with Lynch syndrome for bowel cancer, as their genetic predisposition places them at higher risk. This approach just needs to be fully taken on board. It is really the correct, most intelligent way forward, rather than the one-size-fits-all approach.

Multidisciplinary

Our researchers have identified hundreds of genetic variations and gene mutations which can switch protective tumour suppression genes off, as well as moderate and high-risk genes for many cancers, but we need to go further.

We have refined this approach by analysing DNA samples collected through the Predicting the Risk of Cancer at Screening (PROCAS and PROCAS-2) studies using exome sequencing, to identify all known and suspected breast cancer genes and assess known breast cancer gene mutation risk.

We recruited 58,000 women from Greater Manchester into the Predicting the Risk of Cancer at Screening Study (PROCAS) and now over 1,700 breast cancers have occurred in those 58,000 women.

We created an algorithm that pulls the different elements of the risk together. We used a risk programme where you have to collect a number of risk factors from each woman. We are now in the process (PROCAS 2) of giving back risk information within six weeks of a woman attending for her mammogram, including all of her risk factors and mammographic density.

In a subset of women, we're going to be adding in the genetics by collecting saliva DNA when they come for their mammogram. We'll extract DNA from the saliva and run a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array and then generate from 143 of these common variants, a polygenic risk score. That might give them a risk anywhere between 0.25, so a quarter of the average risk, or it might give them a four-fold relative risk. Yes, that's a very big risk range, but also a very accurate one.

When it predicts a higher risk, it is a higher risk. When it predicts a low risk, it is a low risk - and it's accurate.

This work brings together geneticists, oncologists, epidemiologists, and radiologists to make this happen, along with image scientists and IT specialists.

Single point for risk prediction

Ultimately, the aim is that when a woman is around 40 years of age, we will be able to do a full risk assessment for all the female cancers, not just one, and then work out a screening programme.

Currently, the expensive part is the genetic testing which probably costs around £80 a test, but this isn't desperately expensive when you consider that if used accurately, then you're saving £80 for every mammogram you don't need to do, so you'll save money by better targeting.

I would like to see Manchester become the go-to place for risk stratification, prevention and early detection of all the major common cancers. My colleagues have identified new genes that haven't been identified by other groups around the world for inherited cancer syndromes, and this isn't just because of our access to the diverse population. It's because we attract high quality scientists to do the innovative, new research. We need to continue to be world leaders and strive for more, because we can do it.

Learn more about research into cancer prevention and early detection at the Manchester Biomedical Research Centre.

Meet the researcher

Gareth Evans is Professor of Medical Genetics and Cancer Epidemiology at The University of Manchester, and has established a national and international reputation in clinical and research aspects of cancer genetics, particularly in neurofibromatosis and breast cancer.

Photo by Christopher Doyle

Transforming lung cancer detection

A new scheme pioneered at Manchester is transforming lung cancer screening and giving patients a better chance of survival.

Global problem: detecting cancer’s biggest killer

The legacy of decades of smoking and socio-economic deprivation has resulted in Manchester having the highest rate of lung cancer death in the country and it kills more people under 75 than any other disease. The city, however, is not alone in its challenges with the disease – lung cancer is responsible for nearly one in five cancer deaths worldwide.

Mortality rates are so high because the disease is notoriously difficult to detect in its early stages, causing no to very mild symptoms to be presented by patients. As a result, most people are not diagnosed until the lung cancer is advanced, leaving survival rates measured by a few months.

The challenge is to detect the disease as early as possible to help increase survival rates.

Manchester solution: Saving lives through earlier detection

Manchester has a reputation for excellence in lung cancer diagnostics, treatment and research – we are home to Cancer Research UK’s Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence. It was this strong reputation that led the Macmillan Cancer Improvement Partnership, funded by Macmillan Cancer Support, to task us with transforming outcomes for patients with lung cancer.

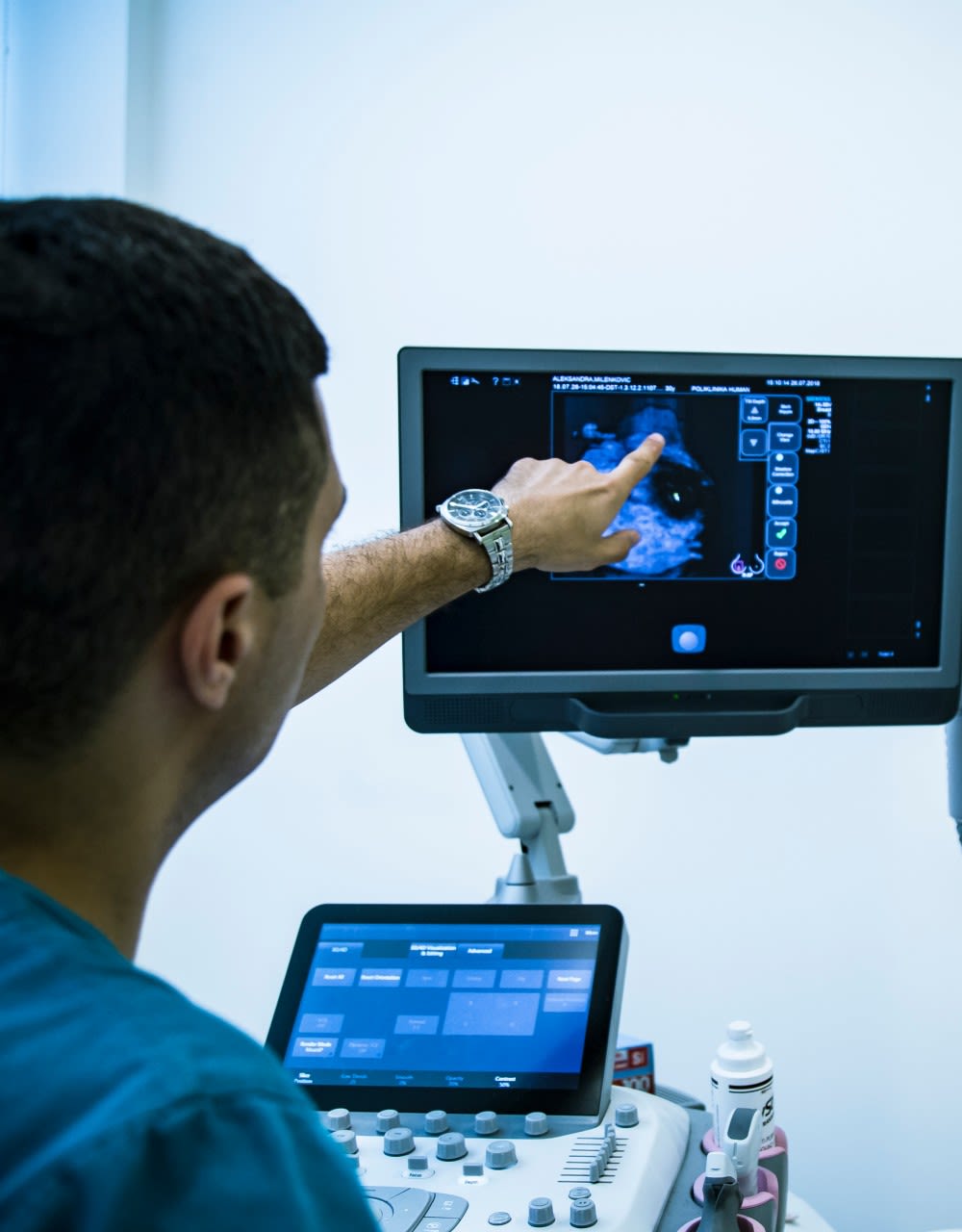

Dr Philip Crosbie, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Cancer Sciences at The University of Manchester and Consultant in Respiratory Medicine based at the University Hospital of South Manchester, led the study and says:

“When asked what needed to be done, with no hesitation we said ‘screening’. It was instant. Waiting for patients to present to us with symptomatic disease leaves things just too late. So it wasn’t a case of asking ‘what should we be doing?’ But more, what does the most effective screening model to increase early detection look like? How do we achieve good uptake in those most at risk?”

The team at Manchester realised that the solution to these challenges could only be found by making the process as easy as possible and to take screening out to the community – and that’s what they did.

"We didn’t call it a lung cancer test because that’s frightening, we called it a lung health check,” explains Dr Crosbie. “These small but important changes worked. People came to see us and demand was very high. Indeed, the success of the screening programme resulted in NHS England announcing that our Manchester screening model will be rolled out to other sites across the country. We’ve achieved a national policy change by designing and delivering an innovative screening approach.”

Life-changing impacts

The University of Manchester’s research has helped to:

- detect a three-fold incidence of lung cancers in the pilot scheme, as compared to the international average;

- change national policy in regards to lung cancer screening by designing and delivering an innovative screening approach;

- demonstrate an ability to move diagnosis from late to early stage disease, which is shifting the balance in survivorship by ensuring more people are diagnosed earlier;

- improve screening uptake in harder-to-reach communities in need.

Find out more

- Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health story: Influencing NHS policy

Meet the researcher

Dr Philip Crosbie, Clinical Senior Lecturer in Cancer Sciences.

Fungal eye infection blinds over half a million in one eye a year

Between 1 and 1.4 million fungal eye infections occur in the developing world per year, leaving over 600,000 people blind in one eye, find researchers from Manchester, London and Nairobi.

Lead researcher Lottie Brown from The University of Manchester recently published the first estimation of global fungal keratitis figures in Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Infection of the transparent cornea of the eye can be devastating, especially if it is caused by fungal keratitis, say the team.

The infection - which often sets in after an agricultural accident - results in visual impairment, blindness and disfiguration. It can lead to discrimination, loss of employment and social isolation, reinforcing the cycle of poverty.

Outcomes of fungal keratitis cases, which are usually diagnosed too late to save vision, are poor: 60% of sufferers will go blind in the affected eye and 10% will need surgical removal of the eye. In contrast early diagnosis usually saves both vision and the eye, although a high level of expertise, antifungal therapy and often surgery is required.

The researchers identified high rates of fungal keratitis in a number of African countries as well as Nepal, Pakistan and India. Lower rates were identified in Europe.

Professor David Denning of The University of Manchester and Chief Executive of the Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections (GAFFI) said: “Fungal keratitis is so neglected among neglected tropical diseases, even the WHO and G-Finder don’t list it. Poor agricultural workers are most affected, yet high quality care can takes days to access in most high incidence areas.

Professor Matthew Burton, practicing ophthalmologist at The International Centre for Eye Health, part of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, declared: “Among all the major causes of eye infection in adults, fungal keratitis is too often devastating. My own experiences in Tanzania, Uganda, Nepal and India taught me what a challenge this problem can be – but enabled my team to develop pathways for major improvements in care.”

Lottie Brown, a final year medical student in Manchester, said: “Having seen these patients first hand in Nepal, I can testify to how awful fungal keratitis is. It has been a privilege to contribute to a better understanding of this ‘infectious accident’ which could affect anyone.”

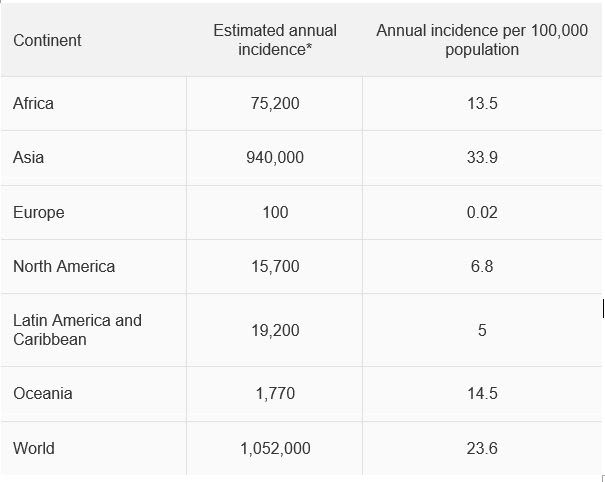

The authors examined all 241 papers published listing the causes of microbial keratitis to derive country and regional estimates of annual incidence. In Kenya, Dr Michael Gichangi from the Ministry of Health had collected cases from each district over several years, enabling an estimate for Africa. The authors also checked for the ratio between fungal and bacterial keratitis which varied from 1% in Spain to 60% in Vietnam, typically ~45% in tropical and subtropical areas.

* rates are ~40% higher if culture and microscopy negative cases are assumed to be fungal.

The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis is published in Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing

Moving towards evidence-based, data-driven responses

Professor Neil Humphrey

In recent years, there has been a significant decline in children and young people’s mental health and, although the full effects are not yet known, the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have contributed further to this decline. Mental health difficulties in childhood and adolescence are repeatedly shown to have long-lasting effects, including poorer physical health, higher rates of criminal behaviour, and lower quality of life in adulthood. In addition to the profound personal consequences, mental health conditions have an adverse economic impact. Higher service utilisation and reduced economic productivity costs around £100 billion per year in England alone. With evidence to suggest that half of adult mental health conditions have their first onset before the age of 14, investing in support during childhood and adolescence should be a key national priority.

The role of schools

School is one of the most significant developmental contexts for children and young people, and teachers are often relied upon to provide pastoral support for them. Teachers view themselves as being on the ‘front line’ in combatting poor mental health among children and young people. This is partly due to cuts to specialist mental health services across the UK over the last decade, which mean that students and parents/carers have to rely on non-specialist allied services, including schools. The government also recognises that schools have a role to play in supporting children and young people’s mental health.

Despite the major role that schools play in supporting children and young people’s mental health, many do not assess the mental health and wellbeing of their students. Of those that do, few use validated methods across whole cohorts. This is problematic because schools cannot respond effectively without reliable data. Additionally, without regular assessment, there is no way for schools to know whether their interventions are making a positive difference for students.

The National Lottery funded HeadStart programme is supporting schools and allied professionals to assess the mental health and wellbeing of their students, and analyse the effectiveness of a range of interventions. Using lessons learnt from the HeadStart project, my colleagues and I will be spending the next three years leading the Greater Manchester Young People’s Wellbeing Programme.

The Greater Manchester Young People’s Wellbeing Programme

The Greater Manchester Young People’s Wellbeing Programme represents a unique opportunity to trigger a step-change in education, such that the assessment system (which currently focuses almost exclusively on academic attainment) is rebalanced to give greater parity to wellbeing and the aspects of young people’s lives that impact upon it. Over the course of three years, we will survey young people, initially in years 8 and 10, in every participating secondary school across the Greater Manchester city-region. We will collate the data from the surveys and return it to schools via an interactive online dashboard, which will help them to understand the state of their students’ wellbeing (and the things that drive their wellbeing).

The dashboard will allow schools to filter their data by a range of characteristics including sex, age, special educational needs, and free school meal eligibility (and combinations of these characteristics) as a means to identify those groups in greatest need of support, thereby enabling them to target scarce resources more effectively. With each iteration of the survey, schools will be able to monitor their progress over time.

Alongside this, the Child Outcomes Research Consortium will be supporting the Programme to assist schools in implementing positive changes based on the data. In addition, neighbourhood data will be published, enabling a genuinely place-based approach to young people’s mental health in which arts and cultural organisations, youth clubs, sports clubs, businesses, charities and other actors work together to address local needs and priorities.

Policy implications

Even without participating in the Programme, schools can still act to improve their mental health provision. Basic training can help to improve teachers’ ability to support children and young people when they experience mental health difficulties. Senior leadership teams should support training to maximise training gains and create a whole-school approach to mental health provision.

Schools should also adopt tried-and-tested interventions for students, including for example the Bounce Back programme, which we evaluated as part of the HeadStart programme. By making the most of these schemes, they can help to prevent emergent mental health problems from reaching clinical levels. However, schools should ensure that they implement such interventions fully to achieve the best results. There are numerous online tools that can guide them towards programmes that have an evidence base.

Using a secure monitoring and assessment tool will equip schools to better support students’ mental health and wellbeing and to assess the effectiveness of their efforts. Generation of high-quality, detailed mental health and wellbeing data, presented in an accessible format, with support from external experts to aid interpretation, planning, implementation and review, enables schools, service delivery organisations and policymakers to make data-driven decisions about provision. The Greater Manchester Young People’s Wellbeing Programme uses such an approach, which, in the long term, could be used in all secondary schools across the country.

Finally, although schools do have an important role in supporting children and young people’s mental health, they are not specialist mental health services. Teachers (and other non-specialist allied professionals) report a lack of confidence when trying to support students who are experiencing mental health difficulties. To support children and young people most effectively, the government needs to re-invest in specialist services. The system can then work in tandem, with schools identifying students who require significant additional support and specialist services being able to provide it.

Meet the researcher

Neil Humphrey is the Sarah Fielden Chair in Psychology of Education at The University of Manchester. His research focuses on what we mean by mental health, why mental health matters, what matters for mental health and what works for mental health in children and young people.

How graphene could treat PTSD

European researchers, including Professor Kostas Kostarelos from The University of Manchester, have shown how graphene can regulate the neurological processes in animals that provoke stressful memories, paving the way for novel therapies for long-term anxiety conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The team behind the study comprised researchers from the International School for Advanced Studies of Trieste (SISSA), Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology of Barcelona (ICN2) and the National Graphene Institute in Manchester, funded by the EU’s advanced materials funding spearhead, the €1bn Graphene Flagship.

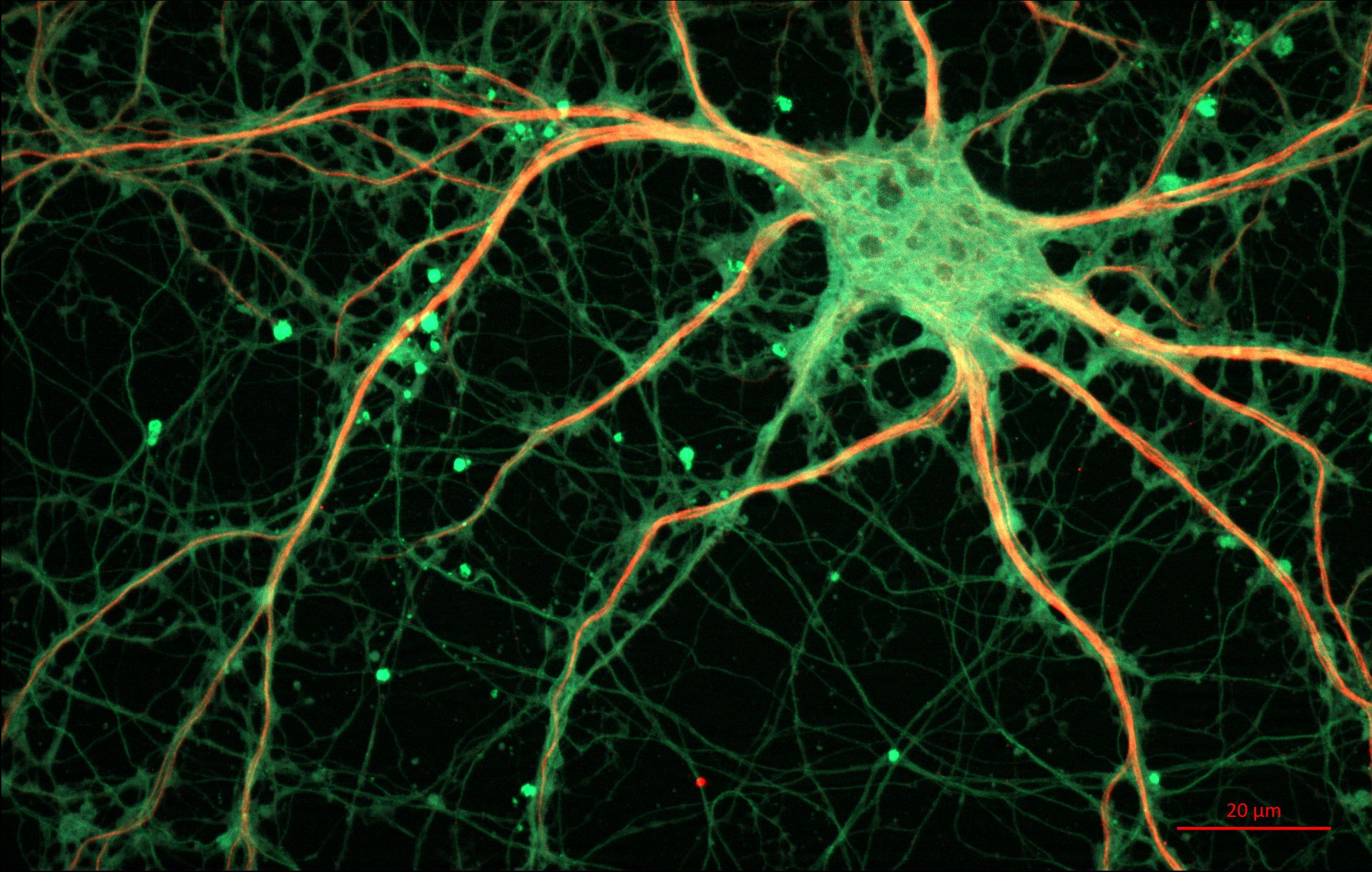

Previous studies by this international group of scientists have demonstrated that small graphene oxide sheets (s-GO) are effective in moderating synaptic hyperactivity: an over-stimulation of the communications between neurons that determine normal (or abnormal) brain function. Now the team looked to put that finding to therapeutic use in a specific part of the brain that deals with stressful or ‘aversive’ memory.

“We wanted to know if the reduction in excitatory synaptic activity was sufficient to modify pathological behaviours,” says Professor Laura Ballerini, leader of the SISSA team.

Laura’s team analysed defensive behaviours caused in rats by the presence of a predator, using exposure to cat odour to induce an aversive memory. If the nanomaterial subsequently administered was efficient in blocking excitatory synapses, it would be expected decrease the anxiety-related response.

“And this is what happened,” adds Laura. “After six days, the animals that were administered with graphene flakes 'forgot' the anxiety-related responses, rescuing their behaviour."

The messenger becomes the message

Professor Kostarelos, leader of the Nanomedicine Lab at Manchester, says the study was the culmination of several years’ work and international collaboration on the use of graphene oxide for targeted therapeutics. And in fact, he explains the graphene oxide sheets were not initially intended to act as a standalone drug at all.

“A few years ago were looking at s-GO as a potential platform for the delivery of other small molecules,” Kostas recalls. “And it was a big surprise that the graphene oxide had this dampening effect on its own when interacting with neurons.

“In itself, that was a real breakthrough but potentially the future for this technology is to use a combination of the graphene oxide sheets and other molecules, delivering therapies for anxiety-related disorders in a highly targeted way that eliminates the adverse side-effects seen in some anti-depressants and tranquilisers.”

Precisely why the s-GO sheets dampen synaptic response remains unclear, although evidence suggests it relates to surface properties and dimensions. Only a specific size of sheet produced the effect, with larger and smaller flakes proving ineffective.

Kostas says this technology is still some distance away from clinical trials, but it forms part of a growing suite of biomedical nanotechnologies at The University of Manchester that are set to revolutionise neurological interventions and the management of brain disorders, from highly targeted treatments for aggressive cancers such as glioblastoma to therapies for migraine and seizures to early detection for Alzheimer’s Disease.

“Everything we are doing is within the context of what’s safely possible,” says Kostas, who stresses the huge amount of work going on at Manchester around safety in the deployment of graphene and other nanoparticles for medical use.

“In a clinical context we need to be very targeted – in a specific area of the brain, in a particular structure within that area and target only that structure. If we see adverse effects, what are the limits that allow us to operate in a therapeutic window that is safe? If we establish that, or if there are no adverse effects, then we take the conversation to our clinicians and surgeons on how to translate these findings into clinical practice. We already have pioneered getting graphene in the first in-human studies and more will follow soon.”

Find out more about the Nanomedicine Lab at The University of Manchester and the Graphene Flagship.

Meet the researchers

Kostas Kostarelos is Professor and Chair of Nanomedicine at the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences of the University of Manchester. He is leading the Nanomedicine Lab that is part of the Centre for Tissue Injury and Repair and the National Graphene Institute.

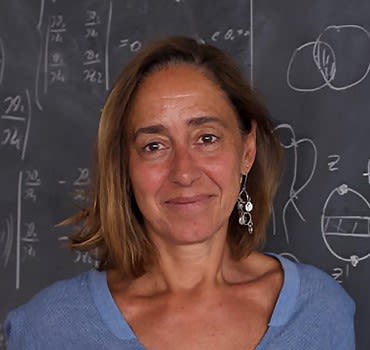

Laura Ballerini is a professor at SISSA. She has been working for more than 15 years on the physiology of spinal cord neurons/networks. Recently, she has worked on the interactions between living neurons and micro-nano fabricated substrates or bioactive-composite containing carbon nanotubes.

New graphene-based antibody test developed for detecting kidney disease

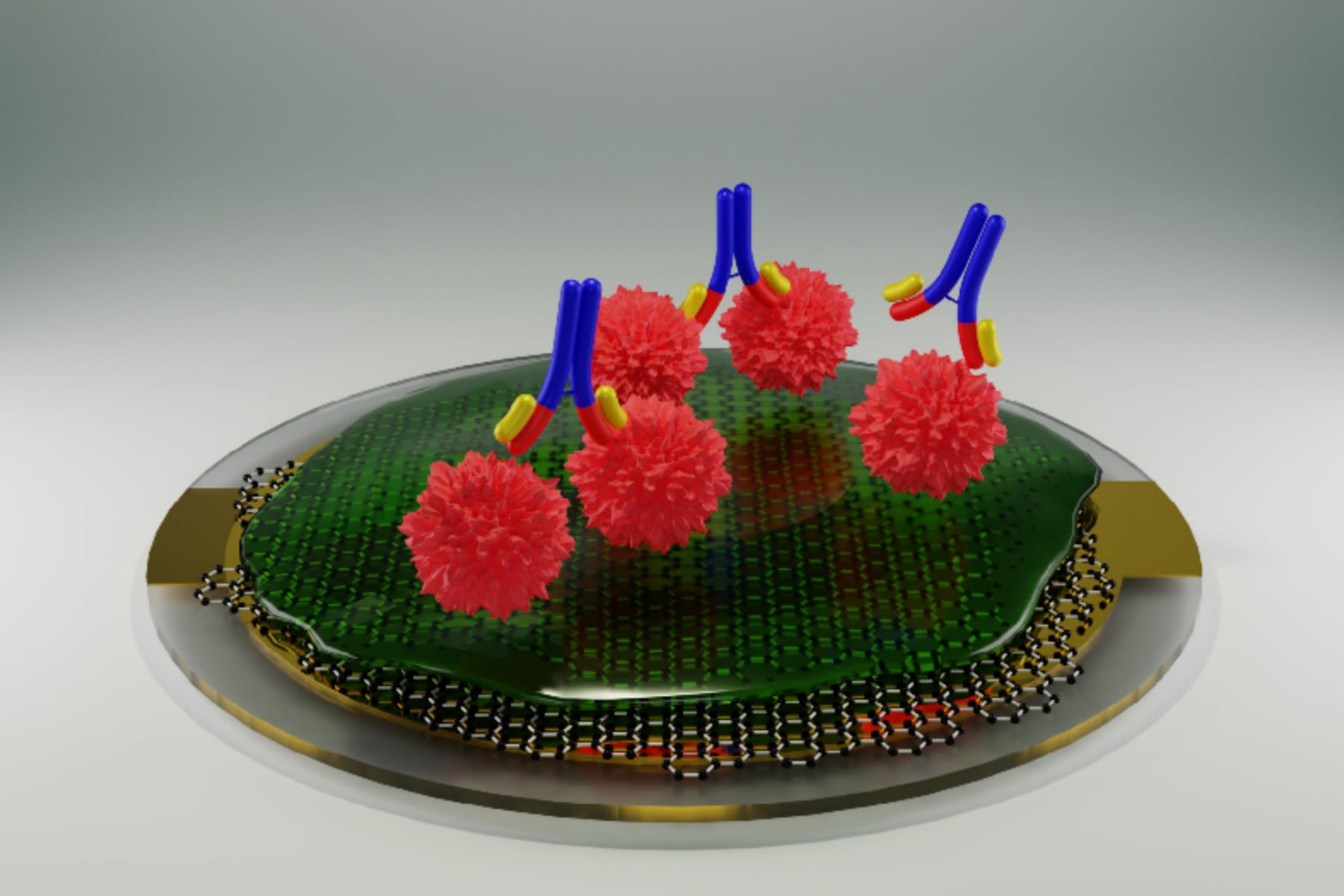

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from The University of Manchester have developed a new graphene-based testing system for disease-related antibodies, initially targeting a kidney disease called membranous nephropathy.

The new instrument, based on the principle of a quartz-crystal microbalance (QCM) combined with a graphene-based bio-interface, offers a cheap, fast, simple and sensitive alternative to currently available antibody tests.

“Our research has the potential to make antibody testing for various diseases more widely available, at the point of care like GP clinics or care homes, rather than just in specialist testing centres”, said Dr Aravind Vijayaraghavan, from The University of Manchester, who is the lead investigator on this project.

The system could also be adapted to test for antibodies to foreign proteins or viral infections, such as COVID-19. “Due to the cheap, fast, simple and sensitive nature of our test, we believe that it is ideal for large-scale deployment in response to pandemics in the UK and elsewhere. In particular, the system would offer significant boost to testing capacity in low- and middle-income countries and remote locations,” added Dr Vijayaraghavan.

Collaborative teams

The team of collaborative researchers from across The University of Manchester including, the Department of Materials, National Graphene Institute and Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health have published the results in two open-access papers in the journals ACS Sensors and Carbon.

The researchers first studied how biomolecules, like proteins and lipids, adsorb on the surface of different kinds of graphene materials such as graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide, which are characterised by different degrees of chemical modification of the parent graphene material.

Based on this study, they developed a method to form a protein-based layer on graphene, which can then be functionalised with specific receptor molecules for antibodies. These receptors ensure that only the targeted antibody will bind to the graphene surface, and nothing else.

While this graphene bio-interface was being developed using a commercial quartz-crystal microbalance system, the authors realised that in order for it to become a widely accessible antibody test system, an alternative read-out instrument was essential.

According to Dr Daniel Melendrez, a Research Associate at The University of Manchester, “A commercial QCM system can cost over £50,000 and cannot be made widely available at the point of care. So, we developed a custom QCM system based on an open-source solution, using all 3D printed parts and electronic circuits of our own design, which costs 100-times less than the commercial system.

“Using our cheap and compact instrument, a healthcare technician can simply place a small drop of sample to be tested on the graphene-coated chip, and the test result will be displayed in as little as 10 minutes.”

Measuring concentration of antibodies

Furthermore, despite being a simple and fast test, this system is also quantitative, which means it can measure the concentration of antibodies in a patient’s sample. This information can be used to determine how severe the disease is, how long the patient has had the disease and whether the patient has developed an immunity either having contracted the disease or from being vaccinated.

Looking ahead, the research team is planning to develop their test for a wide range of autoimmune diseases, where the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues, for example, coeliac disease.

Advanced materials is one of The University of Manchester’s research beacons - examples of pioneering discoveries, interdisciplinary collaboration and cross-sector partnerships that are tackling some of the biggest questions facing the planet. #ResearchBeacons

Meet the researcher

Aravind Vijayaraghavan is a Reader in Nanomaterials in the Department of Materials and the National Graphene Institute at The University of Manchester. He leads the Nanofunctional Materials Group. His research involves the science and technology of graphene and 2-dimensional materials, particularly for applications in composites, electronics, sensors and biotechnology.

The mass spectrometry coalition tackling COVID-19

Inspired by the actions of one Manchester academic, a new international network of more than 800 scientists has formed to diagnose prognosis for COVID-19 patients.

Joining forces to focus on prognosis

When faced with limited access to COVID-19 tests at the height of the pandemic, Perdita Barran, Professor of Mass Spectrometry at The University of Manchester, was inspired to repurpose her laboratory to assist with national testing. She was not, however, able to do it at that point in time.

Similarly, colleagues across the UK and Europe were facing similar issues and joined forces to determine the best use of their skills and resources to support the crisis. They decided that the best use for mass spectrometry – the method of separating and weighing molecules – was to focus on prognosis, rather than diagnosis, of patients. As a result, mass spectrometry scientists looked for risk factor biomarkers to determine whether people would have a moderate or severe response to COVID-19 and the long-term effects it might have on patients.

The new COVID-19 MS Coalition involves more than 800 scientists from 18 countries, including members from the Human Proteome Organisation (HUPO), an international collection of researchers who are identifying and quantifying human proteins with mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry and virus detection

Mass spectrometry helps scientists understand how the virus interacts with the host by investigating the nature of the viral protein and the proteins found at the back of people’s throats – this practice is normally an important step when developing vaccines or therapeutics.

Professor Barran heads up the COVID-19 MS Coalition team at Manchester, leading a £1.8 million grant funded by UK Research and Innovation, which involves five other universities and combines the mass spectrometry capabilities of the Michael Barber Centre and the Stoller Biomarker Discovery Centre.

This project is using mass spectrometry to find prognostic biomarkers to guide clinical decisions and also catalogues all mass spectrometry research data into a single web catalogue. Data scientists around the world can then access the information to see how people are affected by the disease.

Professor Barran is also acting as an advisor to the Department of Health and Social Care, assisting the National Health Service on using mass spectrometry as an alternative testing method to reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Here, the aim is to develop capacity capability for diagnostics and prognostics.

Measuring molecules to help treat patients

“By weighing molecules accurately and monitoring quantity, we can also find out exactly what they are. Molecules can be measured in people with or without COVID-19, however, when someone has the virus the amount of a given molecule changes as a response and this is diagnostic,” says Professor Barran.

“Identifying important molecules and finding out how they change can help doctors treat patients more effectively. This process is used in a lot of illnesses, particularly in blood disorders.”

“Mass spectrometry also measures molecules from bacteria, a common cause of infection and illness, to allow doctors to treat patients with the right antibiotics. One area I’m interested in exploring is: if mass spectrometry can be used in a large collaborative effort in the UK to diagnose coronavirus, could it also be used to diagnose other infections and disease and healthy aging? In Manchester, we already use this process to diagnose Parkinsons Disease.”

Impact of the COVID-19 MS Coalition

The coalition has already produced more than 200 papers that use mass spectrometry to study the coronavirus and there have been numerous studies exploring prognostic markers.

Early COVID-19 MS Coalition studies that took place when disease rates and hospital admissions were high have contributed to a greater awareness of how to treat the virus and an understanding of how people that meet a specific criteria, such as cardiovascular problems or obesity, are affected.

“Coalition members are working together to find solutions to coronavirus so it’s important that we use the same methods, as we want those methods to be adopted by hospital labs,” says Professor Barran.

“I hope this coalition will lead to more collaborative science and that this pandemic allows us to develop public health that is less competitive. I also hope that any new resource being purchased for coronavirus, certainly through mass spectrometry, will benefit the diagnosis and treatment of other diseases.”

“The global data being collected now will be a great future resource as it allows scientists to have knowledge about people’s health and illnesses. The way we’re accelerating rapid diagnostic tests to a point of having them validated and being used by clinicians is a real celebration.”

Read about the launch of the COVID-19 MS Coalition.

Meet the researcher:

Professor Perdita Barran is Associate Dean for Research Development at The University of Manchester and Director of the Michael Barber Centre for Collaboration Mass Spectrometry (MBCCMS).

Area-based vaccination would better protect against COVID-19

Dr Ruth Watkinson and Professor Matt Sutton

The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) phase 1 vaccination goals were to ‘save lives and protect the NHS’, with prioritisation determined by individual risk of severe COVID-19. Other than health and social care workers, prioritisation was determined by age group and health conditions. However, two layers make up the overall risk of severe COVID-19 – firstly the risk of coronavirus infection, and secondly the risk of severe COVID-19 if infected. Phase 1 prioritisation focused exclusively on the second layer of risk, divorced from the context of peoples’ lives such as social deprivation, ability to work from home, or geographical region. Yet, all these factors affect the first layer of risk: the risk of coronavirus infection. For example, a healthy person in their mid-70s (priority group 3) getting supermarket deliveries in an area with low case rates faces a low overall risk of severe COVID-19 because they have almost no exposure to coronavirus. However, they were prioritised far ahead of a 64-year-old (priority group 7) supermarket worker in an area with high case rates, who faces high overall risk due to far-greater risk of infection coupled with moderate age-based risk of severe COVID-19. Following new modelling incorporating ethnicity and postcode, some additional people have been advised to shield and will now be prioritised for vaccination. While this is welcome news, it also tacitly acknowledges the health inequalities generated by fundamental flaws in the original strategy. Sadly, even this meagre progress towards equality has been reversed for phase 2, with eligibility determined exclusively by age.

Phase 2 priorities

The JCVI estimates those eligible for vaccination in phase 1 account for 99% of preventable mortality due to COVID-19. So, while we should guard against any avoidable deaths, we must balance protection from a rare event against other harms and inequalities. We now know the vaccines protect against infection as well as severe disease, so we argue that prioritisation based on the risk of coronavirus infection (not severe disease risk) would be more equitable and more efficient for four reasons:

Firstly, long COVID is an often-debilitating illness that affects many, including those with only mild initial COVID-19. A recent US study found almost 1 in 3 reported persistent symptoms and worse health-related quality of life 6 months after mild COVID-19. Similarly, UK estimates indicate long COVID is common, including amongst children. Importantly, there is no clear association between age and long COVID – the only known risk factor is coronavirus infection.

Secondly, vaccination ‘need’ can be considered more broadly, given the high costs and wide inequalities associated with lost earnings or education due to self-isolation. For example, last autumn term there were wide geographical and socioeconomic inequalities in in-person school time, with children in areas with higher case rates more frequently sent home to self-isolate.

Thirdly, prioritising those with the highest infection risk has societal benefits. Although the vast majority at high risk of COVID-19 mortality will have been vaccinated in phase 1, neither uptake nor vaccine effectiveness are 100%. Nationally, even 95% uptake and 95% efficacy would leave several million people highly vulnerable, risking another surge in deaths as restrictions are eased. Allocating phase 2 vaccinations to those with the highest infection risk first would reduce onward transmission, providing a secondary ‘shield’ to those still at risk. More broadly, vaccination can help drive down infection rates, and targeting areas with persistently higher rates would be the most efficient use of limited supplies.

Finally, targeting vaccines to those with higher infection risk would reduce the opportunities for the emergence of additional variant strains. The risk of variants that evade the protection from current vaccines is a global threat to the longevity of vaccination success, and every additional infection increases the probability of this occurring.

Practical implications for phase 2 strategy

So, how can we practically allocate vaccines to those at highest risk of infection? While many factors play a role, the single biggest predictor is the number of positive COVID-19 cases in each local area at any given time. Although the current national lockdown is reducing new cases, reductions are not shared equally across the country. The latest REACT study data shows that while cases in the South East and London fell by over 80%, rates only fell by 24% in Yorkshire and the Humber, and rates remain particularly high across the North. This mirrors the regional trends last year, when Northern regions suffered higher infection rates, despite sustained damaging local restrictions.

Several leaked official reports concluded rates are – and will likely continue to be – stubbornly high in deprived areas, due to a ‘perfect storm’ of many people in jobs that cannot be done from home, overcrowding, unmet financial needs, and failures of the Test and Trace system. At the time of the leak, Bolton was the worst-affected area with a rate of 98.1 coronavirus cases per 100,000 while Southampton had a rate of just 3.2. It is therefore unreasonable to suggest 20-, 30-, or 40-year-olds across the country face equivalent risks from coronavirus, with geographical differences dwarfing age-based differences in hospitalisation (3-fold increase per decade). Instead, it would be far more equitable to prioritise local areas with the highest case rates, and where ‘R’ – the spread of cases – is highest. This is entirely feasible with close-to-real-time data available from REACT and daily testing figures.

Importantly, this approach would increase access to vaccination for those from ethnic minority groups, who have suffered disproportionate impacts from the pandemic. Systemic racism has put people from ethnic minority groups at higher risk for a range of reasons, from being more likely to have jobs with higher exposure and feeling less able to raise safety concerns at work, to being more likely to live in neighbourhoods with higher case rates. While other risks stemming from racism are complex to address, prioritising areas with highest infection rates is a straightforward way to increase prioritisation of many people from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Perhaps most importantly, prioritising protection against coronavirus infection risk is not at odds with the goal of protecting against the rarer but serious outcome of severe COVID-19 amongst the under 50s. In reality, these goals align, because the overall risk of severe COVID-19 is so highly dependent on who is the most exposed to infection, particularly as national case rates fall and inequalities in local rates become increasingly stark.

Meet the researchers

Dr Ruth Watkinson is a research associate in the Health Organisation, Policy and Economics (HOPE) group at The University of Manchester. Her research focuses on health inequalities, in particular looking at inequalities between ethnic groups and socioeconomic groups.

Matt Sutton is Professor of Health Economics, joint lead of the Health, Organisation & Economics research group and Deputy Director of the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration for Greater Manchester.

Health messaging in the vaccine rollout: the role of the community

Professor Prasenjit Sarkhel and Dr Upasak Das

Although the process of COVID-19 vaccination has gathered pace in high income countries, the situation appears bleaker for low and middle income countries. Against the backdrop of increasing human interactions, and limited evidence on vaccine effectiveness compared to efficacy, stricter adherence to social distancing and hand-washing measures continues to be a crucial pandemic management strategy. However, the cautionary notes necessitates the need of hand washing and social distancing in the post inoculation period. Premature complacency in personal hygiene measures might come at a high health cost, especially for the elderly and people with co-morbidities.

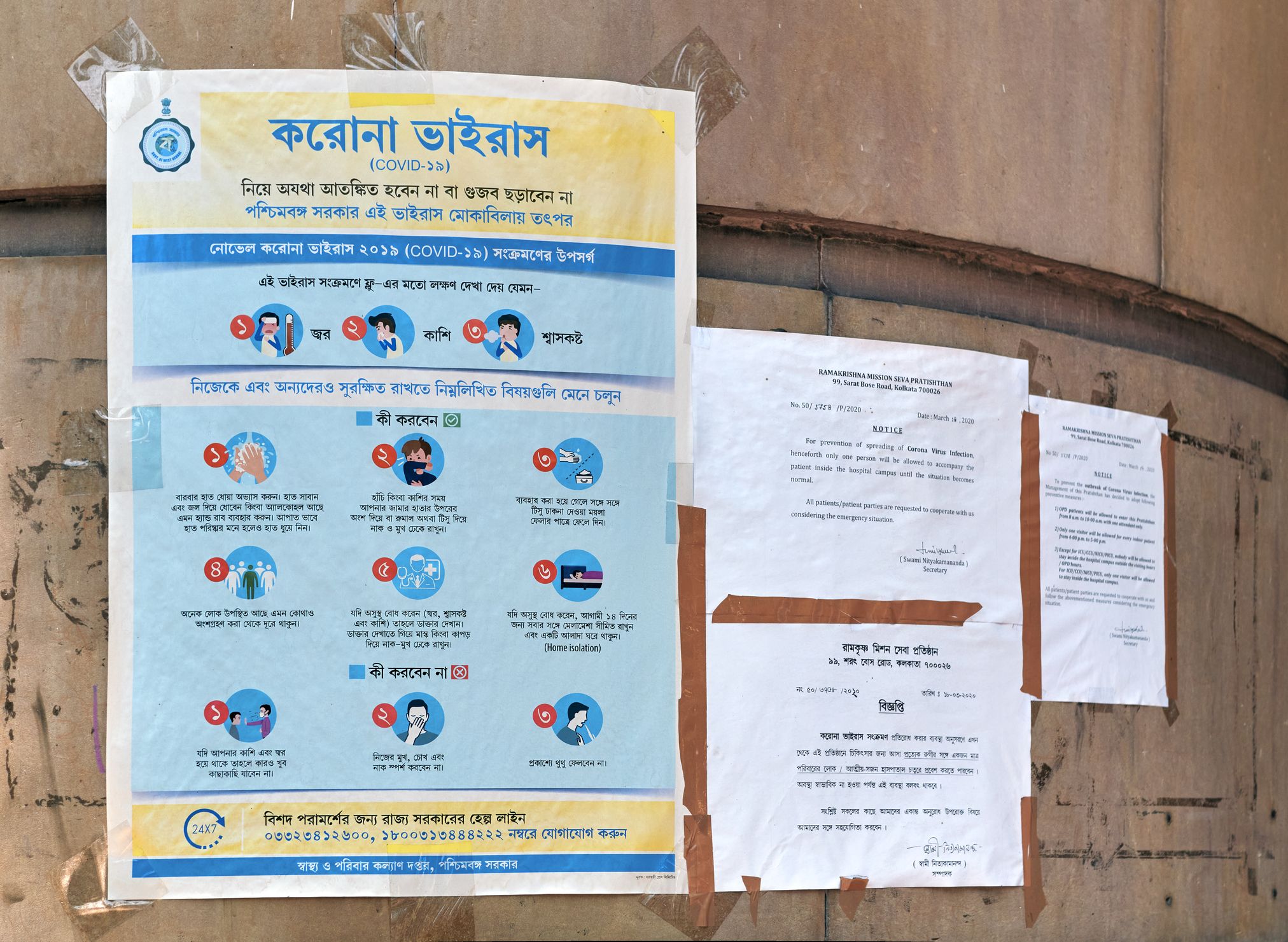

One compelling reason why social distancing must continue is that vaccine doses are unlikely to reach everybody in one go. This is especially true for low and middle income countries, largely characterized by high population density, poor health and weaker institutions. It is also feared that African countries may be left behind in the vaccination drive because of hoarding by richer nations prioritizing their own populations. As such, adherence to non-medical interventions remains a key weapon against the spread of coronavirus, especially as the virus is mutating into newer strain with higher infectivity. Using online survey data collected from India during the lockdown, we offer ways to include communities and create incentives for people to follow these protocols.

Actions like mask wearing and maintaining physical distancing cause discomfort to individuals but confer a collective benefit to society at large. It follows, then, that pro-social motives might be an important driver of behavioral change that would sustain these practices even as vaccines are deployed. Evidence shows that fines have not been fully effective in curbing speed limit violations. Additionally, often people are found to resort to bribing the regulatory personnel and get away with norm violation. So what are the alternative options that would trigger public awareness and induce adherence to social distancing?

Public messaging regarding COVID-19 protocols relies on putting the onus of best practices on the individual themselves. While it certainly informs them about the personal health hazards of flouting social distancing norms, it also emphasizes that the effort is also borne by the individual. However, as behavioral studies have pointed out, individuals often volunteer for social causes if they believe a sizeable part of their community are also engaging in such action. Could such inducements also work in sustaining adherence to social distancing measures? Would the knowledge that others in their neighborhood are also undertaking painstaking compliance measures encourage individual preventive effort?

Our survey data, collected through online platforms between April and May 2020, provides some answers. Responses were collected from 934 individuals, mostly from cities but also suburban and rural areas. The idea was to collect information about individual responses to the pandemic and adherence to common lockdown protocol measures that include social distancing and wearing masks. We also collected their perception about the community on these protocol adherences. In particular, we gathered information on the perceived prevalence of individuals in the respondent’s community who follow these protocols. For example, we directly asked the respondents: Out of 10 people in your community, how many do you think have put on face-masks while stepping outside?

Our analysis of this data found that respondents who have higher perception of their community’s adherence to COVID-19 protocols were on average considerably more likely to better comply with the lockdown protocols and maintain social distancing. We established that individual levels of adherence to the protocols are, to some extent, driven by whether one perceives their community and neighbours are complying with COVID-19 norms. Importantly, we also find this causal relationship to hold for co-morbid respondents. One major observation is a significant decline in compliance levels with subsequent lockdowns, though we argue that if a community complies with the norms, the chance of reduction in individual adherence with time is lower.

The findings suggest immediate potential reforms in the nature and content of the public messaging campaigns for COVID-19 protection in India and other developing countries with strong social networks. To sustain compliance over a longer period of time, framing compliance tasks in terms of community impact might be more effective than financial penalties. Social distancing measures and wearing masks are positive behaviors that should be made visible to encourage them as the norm. This could be done via social media platforms to engage peers and broadcast the use of masks and safety measures. Additionally, targeted interventions in local public health centers, hospitals, or pharmacies, where the likelihood of individuals with a high-risk from COVID-19 visiting is higher, could be useful in reaching this group. Focused interventions related to community compliance, through posters or periodic announcements in these places, can be a good way to reinforce these motivations. In short, telling people to do things because others are doing them, as opposed to penalizing them for non-compliance, might ensure better protection until the vaccine is fully rolled-out. Even if there is resistance to compliance within the community, examples drawn from similar communities can be used as a starter. Once this resistance subsides, messages using examples from within the community can start. This can be done by utilizing local community health workers and reorienting the existing COVID-19 messaging with active participation of the stakeholders, including the national government or Civil Society Organizations among others.

Meet the researchers

Prasenjit Sarkhel is an Associate Professor, Department of Economics, University of Kalyani, West Bengal India. His teaching and research interest are in the areas of development economics, applied econometrics and economics of household behavior in developing countries. He has published in research finds in international and national journals of repute and frequently contributes articles in popular media outlets.

Upasak Das is a Presidential Fellow of Economics of Poverty Reduction at the Global Development Institute at The University of Manchester. He is also an affiliate of the Centre for Social Norms and Behavioral Dynamics at the University of Pennsylvania. His primary research interests include Development Economics, Social Norms, Political Economy, and Public Policy.

Understanding how COVID-19 behaves

Researchers at The University of Manchester are using their expertise in immunology to better understand how the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) behaves and affects individuals.

Working with Manchester’s major hospitals has enabled immunologists to test live patient samples, leading to discoveries about why some patients respond better to certain therapies than others and why some develop more serious forms of the disease.

Harnessing their knowledge of the immune system, our experts will be able to discover how the virus responds in different patient groups, which will lead to better patient outcomes by allowing clinicians to take a more personalised approach to treatments.

The challenge

The challenge is massive but achievable, given the context and immediacy of the current pandemic. Researchers and scientists across the globe are looking at how best to treat COVID-19 in different patient groups.

Understanding the differences in immunological responses to the virus is key to identifying which groups will develop more serious forms of the disease and those who are likely to respond better to certain therapies. This knowledge is critical to ensuring patients receive the appropriate therapies at the optimum time.

The search for a solution

The University’s access to extensive facilities and a large collaborative research community means it can provide a rapid response to the need for increased COVID-19 knowledge.

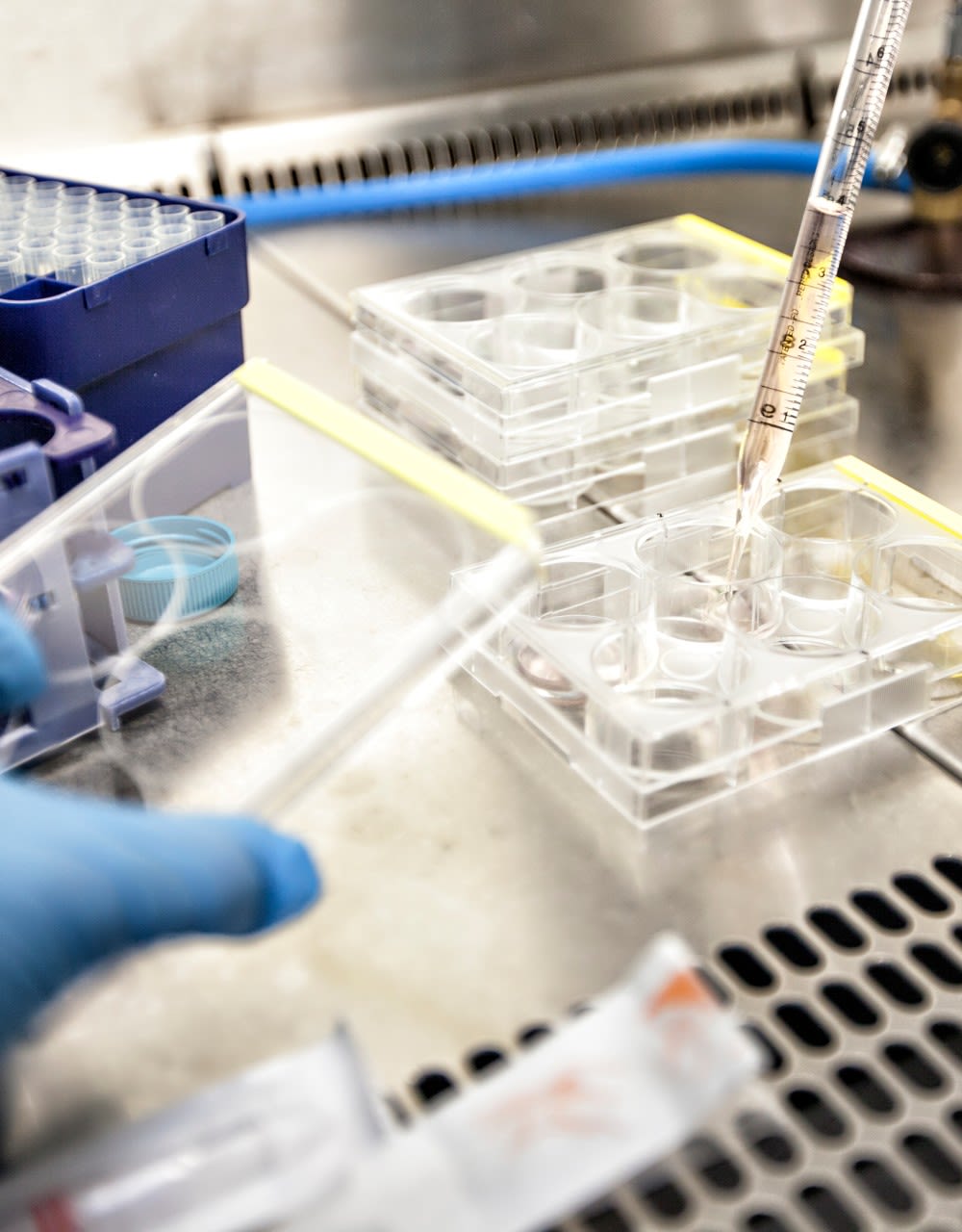

The mechanistic study is being led by Professor Tracy Hussell, Director of the Lydia Becker Institute of Immunology and Inflammation, who, along with her research team, will help to visualise the virus – a first step in understanding how to treat it.

Professor Hussell says: “We’re trying to get an indication of the tipping point in the disease to identify which patients are going to improve, which are not, and where those changes are that will determine this. We’re also testing existing therapeutics to ensure different patients get the most appropriate treatment for them.

“This knowledge will provide insights that will allow for a more personalised approach to the management and treatment of the disease, including which patients receive which therapeutics at what point in their illness.

“The immune system underpins your ability to clear the virus, but it also underpins the severity of the disease that you get. We have a team of researchers willing to handle these infections in order to help expedite this knowledge and improve patient outcomes.”

Fast and agile

Manchester’s ability to rapidly pull teams together has been put into practice, leading to a national hub for knowledge to help expedite understanding of the virus.

“Manchester has been able to turn this around really quickly,” concludes Professor Hussell. “We benefit from a highly collaborative research community who all want the best outcomes – everyone has turned all of their expertise to this disease.

“This is what Manchester is best at: working together to progress knowledge.”

Meet the researcher

Professor Tracy Hussell is currently the Director of the Manchester Collaborative Centre for Inflammation Research (MCCIR) at the University of Manchester.

Addressing the health impacts of night shift work

Professor David Ray

Many people now work night shifts – in developed countries it is one in five. There have been concerns about the impacts of night shift work in mental and physical health, but until recently a causal link was elusive. There are many reasons why people work nights, including increased pay rates, lack of choice, or family responsibilities. Shiftwork is associated with other health risks, including smoking, and lower socioeconomic status.

Nightshift work increases the risk of mental health issues, including mood disorder, and sleep disorder. In addition, there is an increase in the risk of metabolic diseases including obesity, and diabetes, malignant diseases, including breast and prostate cancers, and inflammatory diseases, including asthma.

New information identifies that night shiftwork carries a clear, and significant risk to mental and physical health, even after other factors such as smoking, have been taken into account. Importantly, we now understand why shiftwork carries the risk. This is misalignment of the biological clock in the worker with the external light-dark environment. This is a major advance, as it offers a rational target for intervention to protect the health of nightshift workers.

The negative health impacts of night shift work

Nightshift work is unpleasant, and typically attracts higher rates of pay in compensation. Some nightshift workers are unable to continue in role due to immediate difficulties in coping.