Working Futures

Foreword

Automation and AI, digitalisation, remote working, environmental change, and ageing are having profound impacts on the world of work. We talk about the ‘future’ of work, but these trends are already impacting the jobs people do, how we work, where we work, when we work, and the skills people need for work.

There are many predictions about the impacts of artificial intelligence or AI on the workforce. How many jobs might it displace and create? To what extent can it increase worker productivity? Who is likely to be most affected? But ChatGPT is already used by more than a billion users for coding and writing, while the number of AI patents increased four-fold between 2005 and 2021. The use of algorithmic management systems, AI-enabled tools and technologies developed to remotely manage workforces, is becoming more widespread in factories, hotels and wholesale warehouses, alongside the digital labour platforms where most of the debates have focused. McKinsey predicts that 70% of companies may adopt at least one type of AI technology by 2030.

It is difficult to predict how these trends will impact different groups of workers and places. There are big questions about the impacts of AI and the transition to net zero.

Learning and Work Institute’s analysis shows individuals with certain protected characteristics have experienced greater increases in flexible working arrangements, self-employment and work in jobs at high risk of automation than the wider population. For example, the number of disabled workers on zero-hours contracts was 194% higher in 2021 than it was in 2013, while the number of non-disabled workers on zero-hours contracts was 95% higher. If these trends continue, ethnic minorities, older workers and disabled people will be overrepresented in the gig economy, self-employment, and industries at risk of automation. There are potential benefits and pitfalls to these trends, either through these groups enjoying greater flexibility in their work, or by contrast suffering from increased job insecurity, precariousness and pay inequality.

The UK already faces significant labour market challenges. The nature of weak economic growth means that workers are facing almost two decades of lost pay growth and average real wages are £11,000 per year lower for a full-time worker than if pre-financial crisis trends had continued. While increases in the minimum wage have significantly reduced the prevalence of low pay, volatility and insufficiency of hours in low-paid work has contributed to concerns about the quality of work for many.

Progression from low pay is also limited. Only one in six low-paid employees move on to consistently higher wages over the course of a decade. Our research shows that women, people with caring responsibilities, people with low or no qualifications and people living outside of London are more likely to get stuck in low pay.

With the weakest employment recovery in the G7 and long-running participation gaps, the UK also needs to look at how it can support more people to find and stay in work. The UK is the only country in the G7 with an employment rate that is lower than pre-pandemic, and halving the disability employment gap would mean 1.2 million more people in work.

One in five people (1.7 million) outside the workforce say they want to work. Helping them do so means widening access to employment support (only 1 in 10 out-of-work disabled and older people get help to find work each year). It also means providing more support and flexibility for people with disabilities and long-term health conditions, people with caring responsibilities and help for older people to stay in work.

Ensuring labour market inequalities don’t widen further and more ‘good jobs’ are available to more people means developing a comprehensive, cross-government strategy for good work with employers and trade unions. A strategy that creates good jobs – jobs that pay at least enough to meet everyday needs, provide stability and security, with opportunities for development and progression – requires looking beyond the minimum wage to the reform of employment laws, sick pay and the role of sectoral collective bargaining. Policymakers should also explore how innovation and technological developments can be shaped, in part through regulation, to ensure as many workers benefit as possible.

The contributions in this Policy@Manchester publication consider the policy implications of a range of these issues. The articles consider the impact of changes in the labour market from a range of different perspectives – and, crucially, present evidence-led ideas about how we might address challenges and tackle inequalities.

Naomi Clayton

Deputy Director at Learning and Work Institute

Don’t worry about the future, what about the ‘now of work’?

Mat Johnson and Eva Herman

Amongst all the competing predictions about what the future of work might hold, the challenges of achieving decent work in the foundational economy have been largely overlooked. Here, Dr Mat Johnson and Dr Eva Herman argue that the focus should be on making tangible improvements to the working lives of those in the frontline roles that keep our communities fed, educated, safe, connected, and cared for.

- Frontline roles are underpaid and undervalued – and many countries including the UK face significant shortages of workers to fill these roles.

- A real living wage for workers is needed along with training and development opportunities.

- A greater recognition of the social and economic value of foundational economy jobs begins with a ‘bundle’ of progressive human resource management practices.

Visions for the future of work

Debates on the future of work have tended to align with one of two positions. The first offers a broadly optimistic vision of increasingly high-skill/high-wage jobs in the ‘frontier economy’ closely tied with technological advancements and productivity gains. In this scenario, work potentially becomes more condensed but better paid (leaving more time for leisure and education) with dangerous and monotonous tasks simply handed over to machines and AI.

The second, more pessimistic, vision of the future of work points to large scale job destruction and displacement as automation and new technologies make certain roles and skills obsolete. Some jobs such as entry-level office and sales roles, and some transportation roles, are predicted to disappear entirely from the labour market within a generation.

Regardless of whether we align ourselves with the optimistic or the pessimistic vision, this kind of crystal ball gazing around the future of work distracts us from understanding the challenging ‘now of work’ in the large, but often overlooked, foundational economy. The foundational economy (FE) encompasses many frontline health, social care and emergency services, along with education and childcare, retail, transport, energy, and utilities.

The significance of the foundational economy

Although its component parts may seem somewhat disparate, the FE is significant and directly provides jobs to more than 40% of the UK workforce. In contrast with some professional and technical roles, many jobs within the FE are less at risk of displacement and automation in the near future. The everyday activities within the FE are by their nature localised and difficult to offshore given that the point of production and consumption are geographically ‘tethered’ within communities and neighbourhoods.

Although technology will undoubtedly change the way in which people work, the International Labour Organisation predicts that human health and social care is one of the few growth industries that can create jobs that are inherently low carbon. Growth in health and social care could also reduce the burden of unpaid care that falls mostly on women.

However, many countries are already facing significant shortages of workers to fill these roles. In the UK, for example, at the end of 2022 it was estimated that there were 165,000 vacancies in social care (up by 52% from the previous year), and the turnover rate was close to 31%. Similarly, in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) turnover rates have been estimated at around 28% in the private sector, and providers report running at below capacity because they are short-staffed. Many workers are leaving frontline care and early education for retail jobs that pay similar (or even better) rates of pay but with fewer of the physical and emotional demands.

Skills, productivity and value

Part of the reason for high turnover and vacancies is that such roles continue to be low paid and under-valued. Median wages in elder care are around £11 per hour and in ECEC are around £10 per hour. Workers report being paid the minimum wage for most of their careers.

The conventional economic explanation is that such jobs are considered ‘low skilled’ and ‘low productivity’ - but the economic value of the FE is significant. Health and education alone account for around 6% of Gross Value Added (GVA) for England overall, and around 8% of all employment. However, productivity gains are notoriously difficult to achieve in these ‘high touch’ roles without simply cramming more clients into carers’ schedules or asking employees to work off the clock. A stronger explanation for persistent low pay is the gendered pay norms that surround many caring jobs, combined with long-term underinvestment in public services.

Policy recommendations

While growing the frontier economy will be important for the future prosperity of the UK, we need to make careers in frontline health, education and social care more attractive now if we are to avoid a worsening crisis of poor-quality work and patchy services.

Job quality involves a ‘bundle’ of progressive human resource management practices, such as good working conditions, employee voice, and long-term training and career progression routes, which employers often want to adopt but typically lack the necessary resources and expertise. Recent reforms to the care system in Germany have put more money into frontline services while also providing pay increases of 18% for entry-level social care staff and 22% for fully qualified care staff. Similarly, the proposals in Scotland for sector-specific minimum wages of £12 per hour in both early years and elder care are designed to address chronic staff shortages. These investments combined with support for long-term training and career development will promote workforce quality and sustainability, and aim to reduce the recurring costs of high staff turnover.

Better funding for universal basic services, along with a real living wage for workers would help tackle some of these short-term problems, while also providing a platform for a more equitable distribution of earnings in the future. Quebec has shown the importance of reforming the childcare and early education sector to make it more affordable for parents while also improving conditions of employment. Parents pay a flat daily rate of $8.75 for a pre-school place, with pay and conditions of employment collectively negotiated. This ‘universal’ provision led to a substantial rise in labour market participation of women with children aged 3 and 5 from 67% in 1998 to 82% in 2014, and with it a rise of 1.7% in GDP that more than recouped the upfront investments.

High profile pay disputes have highlighted the problem of sluggish wage growth within the health and education sectors, but early childhood education and care and elder care services are often funded from local authority budgets - which have been squeezed significantly since 2010. While individual local authorities have attempted to model good practice through their own commissioning and procurement practices, coordinated reforms are needed to raise the status and social valuation of the caring profession. This would send a powerful signal that jobs in the FE are valuable to society as well as the economy.

Extending working lives – healthy ageing in the workplace

Chris Phillipson

One in three workers in the UK are aged over 50 – with this figure set to rise in coming decades. Current government employment policy is to encourage over 50s to either to remain or return to work. However, the lasting impacts of COVID-19, along with caring, health, and work issues facing older workers, are all challenges for policies attempting to extend working life. As State Pension Age (SPA) for men and women is set to rise to 67 by 2028, Professor Chris Phillipson explores the issues facing government, employers, and older workers themselves.

- Managing health problems in mid and later life is a significant factor, as almost half of those 50-64 have at least one long-term health condition.

- Policymakers need to ensure that good quality, flexible employment is available to support people in middle and later life.

- A national policy for healthy ageing at work would need to embed a variety of measures, with support needed for healthcare, mental health and menopause, in addition to considering the design of work places to ensure provision for the physical needs of older workers.

Older workers and employment

Employment rates for the over 50s have yet to recover from the effects of COVID-19 – standing at 71.2% in August 2023 compared with 72.4 % in 2020. There are also thousands more workers aged 50-64 who are economically inactive than there were before the pandemic. As these figures suggest, a large share of older people leave work before SPA: in 2021, 50% of women aged 60 to 64 and 41% of men.

Poor health is a key driver behind people leaving the labour force. 1.5 million men and women between 50 and SPA are out of work because of long-term sickness. Office for National Statistics (ONS) data indicates that amongst the over-50s who left work early, reasons for not returning to work include disability, illness, mental health issues, stress, and illness from COVID-19.

Reasons for leaving and not returning to work vary between age groups, with people in their 60s more likely to cite early retirement – 48% of 60–65-year-olds cite retirement compared with 25% of those 50-59 who are much likely to cite a health-related reason.

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) highlight the occupational divide between those who are forced out of work before SPA and those able to stay in work longer or who can afford to retire early. Amongst 50–65-year-olds, those whose last job was in caring, leisure and other service occupations account for over half of labour-force exits, despite employing just three in ten workers. In comparison, only 10% of older people who worked in managerial or professional occupations have left or not returned to work due to poor health.

Barriers to employment

The UK government have launched a number of initiatives to tackle these issues. These include extra funding to help the over-50s back into employment. The Department for Work and Pensions have launched a Midlife MOT website to assist older workers with financial planning, health guidance, and career advice. Recent legislation, such as the Flexible Working Act and the Carer’s Leave Act ,may prove beneficial to the over-50s - but barriers remain to encouraging significant numbers to remain or return to work:

Many older workers who leave work early due to health problems do so because of limited support from employers. A survey by the Centre for Ageing Better (CfAB) found that 44% of over-55s had not had access to any support through an employer, compared with 40% of 45–54-year-olds, and 28% of 35–44-year olds.

The type of jobs available to people aged 50 and over may be an issue: two-thirds of the growth in employment since 2008 has been in ‘precarious’ forms of work, including self-employment, zero-hours contracts, and agency work. Whilst such employment might meet the need for flexible hours, they may entail a poor-quality work environment, and lack of training.

What would a policy for healthy ageing at work look like?

The Centre for Ageing Better have put forward the case for a national programme of employment support with a tailored approach specific to the needs of older workers. They are encouraging employers to sign up to their Age-Friendly Employers Pledge and commit to taking at least one action a year to improve the experience of older workers.

Some specific initiatives will be essential from policymakers and employers if the goal of helping people 50-plus to remain or stay at work is to be achieved.

Improving access to occupational health services is vital – possibly assisted by easing the cost barrier for SMEs through reduced National Insurance Contributions for organisations that provide such support.

Challenging ageism in the workplace is also key, with evidence suggesting that 36% of 50–70-year-olds feel at a disadvantage applying for jobs due to their age.

The ‘cumulative disadvantage’ attached to poor quality work needs recognition - people working in difficult physical jobs should have a right to enhanced health care support to monitor the long-term effects of arduous work.

More research is needed to understand ‘what works’ in supporting different groups of workers. As there is currently limited research on interventions to enhance the health of workers around retirement age, this is something that government should encourage and support.

Support in the area of mental health is important given evidence for high levels of depression, stress, and anxiety in the workplace. Support through menopause is a priority for over 50’s women.

Improvements must be made to the design of workplaces, recognising issues relating to the changing physical as well as mental health needs of older workers. Recognising the role of line managers in supporting older workers is also necessary, with the need for specialist training and age-awareness courses necessary for managers at all levels.

Developing a strategy for achieving a healthy ageing workforce will require a range of actions from government, employers, and employees themselves. This has become an urgent priority given a rising SPA coupled with large numbers of people either too ill to work or struggling in employment with significant mental and physical health issues.

Precarious Work: The Consequences for Later Life Security

Kristian Fuzi and Debora Price

The concerning trend of precarious work is increasingly the focus of policymakers and researchers. Here, Kristian Fuzi and Professor Debora Price advocate for greater attention to the multiplicity of sectors and the widening age range of the workforce now affected by these working conditions. Precarious work trends have serious consequences for the financial security of workers in the present and their financial security in later life.

- Insecure work is not a new social issue, with many cases of ‘casual labour’ existing in places such as the Liverpool Dockyards until the late 1960s.

- Precarious and insecure work constitutes the fastest growing section of the UK labour market, with 4.4 million people working on gig economy platforms each week and a total of 6.1 million workers found to be working insecurely, amounting to 19 per cent of the workforce.

- These workers are known to have lower than average levels of income and pension savings and generally experience low pay, financial inconsistencies, high levels of part-time working and self-employment. They often lack access to workplace schemes, and generally earn insufficient amounts to save adequately or financially plan for later life.

Many precarious workers are not in a financial position to save. Our research has shown that where precarious workers can save, they are prioritising those savings for short-term financial resilience above later life security, raising significant future concerns for our social security system and the projection of an ageing precarious workforce.

Researching Precarious Lives and Financial Behaviour

For 12 months between June 2021 and 2022, we conducted research with 24 precarious workers from across the UK. Each worker was asked to keep a financial diary and take part in two interviews. The workers were aged 28-52 years old, included men and women, and at the first interview were facing insecure conditions as freelance, self-employed, fixed-term, part-time, or zero-hour workers. The project was designed to understand the everyday financial lives of participants by investigating the impact of insecure working practices, social support, household inequality, and gender inequality on their engagement with later life financial planning.

A key issue that emerged across the research sample was the financial constraints that insecure working conditions placed on participants. Fixed-term workers lived with the monthly or annual uncertainty of ending contracts. Those working part-time received an income that frequently only covered their households’ basic financial needs. Freelance, self-employed, and zero-hours workers lived with the weekly uncertainty of income fluctuations. The workers in this study frequently displayed a strong work ethic, expressed passion for their work and a sense of personal fulfilment from their working lives. It was not the notion of work that defined their precarious position, but rather the uncertainties in income associated with it.

Uncertainty and insecurity – housing and saving

A further issue of precarity beyond work for many of the participants was the uncertainty, risk, and costs associated with housing. Workers who were renting expressed a sense of power imbalance with landlords where rent could be raised at an unknown point, with little leverage to improve their housing conditions. Those workers attempting to escape the uncertainties and high costs of the rental market described how income inconsistencies made mortgage applications problematic. Moreover, in cases where workers were existing homeowners, the insecurity and risk of income inconsistency remained a persistent problem with fixed-term mortgage agreements. Whether renters or homeowners, financial inconsistency coupled with deregulated markets laid significant levels of risk and uncertainty on these workers.

These everyday experiences of insecurity felt across their work and private life came to shape and limit their financial choices. By providing a contextual understanding of these workers' everyday lives, it was possible to understand why a precarious worker may or may not be saving for later life. Where workers were not engaging in saving behaviour, their everyday insecurity maintained a focus on their present issues of financially getting by or surviving.

Workers engaging in saving behaviour were revealed to have less contextual insecurity, enabling a focus beyond the immediate - but still, largely, short-term. This resulted in them prioritising greater financial security in their present conditions above later life security. Of the 24 participants in the study, 18 were not engaging in saving for later life at all, with only 3 of the remaining 6 participants engaging in a level of pension saving to ensure sufficient financial security for later life.

Policy recommendations

There is currently a paucity and fragmentation of government data concerning the extent to which precarious working conditions feature within the UK workforce. Part-time work, for example, often involves a more formal contract with a regular income. However, individuals working part-time are struggling to survive financially and failing to save for their later life security; this research identifies both these financial difficulties as features of precarious lives.

- Clearer lines need to be established defining which working contexts are insecure, with greater recognition of the financial limitations such insecurity brings to individual lives. By gathering accurate representations and levels of insecurity amongst the workforce, governments are in a stronger starting position to observe the extent to which financial constraints are a problematic issue for workers in the present and in later life.

- Government also needs to pay much more attention to the more financially vulnerable members of society, in relation to the pension system. Our research brings into question whether a pension system relying heavily on the private sector for sufficient income in later life is capable of providing long-term financial security in an increasingly differentiated and precarious job market. As the findings from this study reveal, the present pensions system is failing precarious workers in achieving any form of adequate financial security in later life.

As part of a long-term strategy, government needs to engage with, and work to remove or compensate for the financial barriers and inequalities that precarious workers face. This process must recognise that such financial barriers and inequalities exist beyond working lives, and appear in everyday lives in forms such as housing uncertainty. In doing so, government will enable greater opportunity for more workers to think about and engage in later life saving.

Implications of the digital revolution for the nursing workforce

Dawn Dowding and Sarah Skyrme

As the largest professional group in the healthcare workforce, nurses have been at the frontline of a digital transformation. In this article, Professor Dawn Dowding and Dr Sarah Skyrme assess what this means for the workforce and suggest policy interventions.

- Ambitions for all NHS organisations in England to be paperless by 2024 will significantly impact the nursing workforce.

- Training, recruiting, and retaining nursing staff has become a key challenge for the UK - as recognised by the recently published NHS Long Term Workforce Plan.

- Strategies are needed to ensure digital infrastructure is in place and the workforce are fully trained in digital skills.

The nursing workforce and the NHS Long Term Plan

Globally, nurses account for nearly 50% of the healthcare workforce, and in the UK are proportionately the largest professionally qualified group of clinical staff. The UK has a shortage of qualified nurses, with an estimated 11.8% of roles unfilled. Nurses work across multiple settings such as mental health, children’s and learning disability services, in the NHS, the care sector, and for private companies.

The NHS Long Term Plan highlights how failure to address recruitment and retention will result in significant shortfalls of community nurses and mental health nurses in the NHS. Up until now, the UK has relied heavily on the recruitment of registered nurses from other countries, often from areas of the world facing their own nursing workforce challenges. Strategies outlined in the Workforce Plan, such as increasing the number of nurse training places alongside new training approaches (such as apprenticeship routes) will increase the number of nurses trained and recruited. However, policymakers in government and the NHS should also prioritise retention of the nursing staff we already have, providing opportunities for skills development to meet the challenges of caring for an ageing population with complex care needs.

Technological innovation, particularly in relation to Artificial Intelligence (AI), is frequently regarded as a viable solution to these challenges.

The ‘future’ health and care system

AI can undertake roles and responsibilities previously carried out by healthcare professionals (for example supporting decisions based on mammography images). While it is difficult to predict precisely what role some advanced technologies may have in terms of future nursing practice, it is evident that nurses’ work has already altered irrevocably since the pandemic, and this evolution will continue.

Healthcare is moving towards delivery models focused on providing care to individuals in their home or community, rather than the previous model of hospital-focused care. The national rollout of ‘virtual wards’ exemplifies this; individuals being cared for in their own homes via remote monitoring technology and care support, rather than receiving care in a hospital setting. The role of ‘diagnostic hubs’ and mobile screening, where health and care services are embedded in or visit local communities are also increasing.

Primary care, outpatient clinics and mental health services now provide telephone or video consultations alongside more traditional face-to-face appointments. We are also witnessing a greater emphasis on individuals taking control of their health, with an increased uptake in the use of mobile health technologies designed to support health and well-being.

What the transformation of care service delivery means for the nursing workforce

Moving to a digital environment with care provided remotely and contact via digital technologies rather than face to face, provides both challenges and opportunities for the existing nursing workforce.

Nurses of the future must be adept at using digital tools. Digital technologies have the potential to free up nursing time; one potential outcome of the generation of AI-based tools is that they will take on routine tasks and administrative duties. This could lead to a shift in the approach to staffing services that may encourage some nurses to stay in practice longer, as well as providing opportunities for delivering care in individualised, remote ways.

We can envisage a time when the general population will be holders of their own health data and manage their care options and health conditions using digital tools. This requires a change in relationships with health care professionals (not just nurses) and organisations that deliver care. For nurses, the skills to react and adapt to new realities and ways of working, (vital during the pandemic) will continue.

Current problems with digital infrastructure

For any digital solution to work effectively, you need good infrastructure, including Wi-Fi and access to the appropriate hardware and software. Nurses work across a variety of organisations, including acute hospitals, community organisations, homes, and the care sector. Our research highlights how in many areas of the country and across organisations these basic requirements are not met. There is a lack of equality in availability of internet access among the general population, with individuals on the lowest incomes (and often the highest healthcare needs) more likely to be without internet access or devices to connect to Wi-Fi.

Our study highlights how this inequality in access extends to nurses. Some organisations provide high quality internet access and devices to their staff – others are reliant on substandard digital infrastructure. Some nurses reported that they worked in environments with unreliable Wi-Fi and either lacked access to enough devices or were expected to use their own devices. Our study survey found that nurses who cannot afford a smartphone or equivalent device can be disadvantaged in terms of ability to perform their duties, with a respondent stating “Accessibility of smart phone, some staff can’t afford these”. Although nurses’ starting salary is £31k, many nurses work part-time and have childcare responsibilities. Considering living costs particularly in the South East of the country, it is quite possible that part-time nurses cannot afford this type of technology.

For many staff, the vision of a digitally-enabled, AI-supported care system is far removed from their current experience. If we are to enable the nursing workforce to work in new ways, then in the short-term, addressing inequalities in access and prioritising high quality infrastructure is key for health policy.

Digital literacy in the nursing workforce

In addition to a working digital infrastructure, the workforce needs digital skills. Over the last three years, there has been an expectation for healthcare professionals to adopt a variety of different technologies and tools. In nurses we found the most common technologies introduced included tele/video conferencing for online consultations, electronic methods for communicating between professional groups, and a variety of digital tools for remote monitoring of patients and documentation of care (such as electronic health records). These were introduced into a nursing workforce with significant variation in their ability and skills to use them effectively, and often with insufficient training.

Ensuring that the workforce has the skills it needs to use the current digital technologies deployed in the NHS and across the wider care sector is a challenge for health and care organisations and educators alike. Many NHS organisations have recognised this and have put strategies in place to provide strong professional nursing leadership in the form of Chief Nursing Informatics Officers or CNIOs - we recommend that this rollout continue apace.

As well as leadership, resources to enable nurses to develop digital skills are required. Many organisations offer their own training, and NHS England has produced a number of digital capability frameworks, though currently not one specifically focused on the nursing workforce. In addition, we need to ensure that nurses graduating from education programmes have the skills to perform in a digitally-enabled NHS.

It is often assumed individuals who have ‘grown up’ with digital technologies and use them daily will automatically have the required skills. However, it is clear from our research that this is not the case, and teaching students to use the types of tools currently used in the NHS and care sector requires a well-targeted approach. This also demands an academic workforce skilled and adept to provide that education, both currently and with a view to innovations in areas such as genomics and AI, which will require significant revisions to the way training is currently delivered.

Further Recommendations

To conclude, investment and strategy from government and NHS policymakers should focus on upskilling the current and future nursing workforce, as well as academic staff in HEIs, in digital skills competencies. This must involve ongoing training and support for the future, to enable skills development for innovations that are currently hard to predict. Recognition that nurses are essential to the effective and efficient delivery of care services should be included in planning to redesign services, and in the procurement of technologies to support their changing role.

The Politics of Equality at Work in the UK: Who Sets the Equality Agenda

Holly Smith, Miguel Martinez Lucio, Stefania Marino and Heather Connolly

In recent years social movements such as #MeToo and Black Lives Matter have shifted the narrative on equality, and reshaped expectations about treatment in the social sphere and the workplace. Many large corporations, multinational companies, public sector employers and small businesses in the United Kingdom have issued statements pledging their commitments to the broad aims of these movements. In this article, Dr Holly Smith, Professor Miguel Martinez Lucio, Dr Stefania Marino and Professor Heather Connolly evaluate how this opening up of the debate presents an opportunity to formulate genuinely inclusive working practices and policy.

- Workers and their representatives should be included and engaged in the processes and dialogue for change.

- The Equalities Act should be extended to include provisions for negotiation and collective bargaining.

- A public policy strategy of support – similar to the now abolished Union Learning Fund – should be established to fund and support trade union equalities representatives and structures more generally in workplaces to lead on this work on equality.

What shapes workplace equality strategies?

For most of the 20th century, equality legislation in the UK was a complex patchwork of numerous pieces of anti-discrimination law, with landmark pieces of legislation such as the Equal Pay Act 1970 and the Race Relations Act 1976 amended and extended.

In 2010, the Equalities Act combined over 116 separate pieces of legislation into one single Act. It provides a comprehensive legal framework of protection against direct or indirect discrimination - identifying ‘protected characteristics’: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage or civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. Since its introduction, workplace policies relating to equality - often called equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) or ‘equal opportunities’ policies - have been heavily influenced and shaped by its provisions.

While it could be argued that the Equalities Act simplifies legislation for policymakers, employers, and workers alike, it gives greater importance to individual rather than collective employment rights. This is important within a context of both declining trade union membership and collective bargaining coverage (the proportion of workers whose employment contracts and working conditions were jointly negotiated between employers and trade unions.)

Filling this representation gap is a wide set of actors such as EDI consultants and advisors, NGOs, and civil society organisations, who attempt to influence organisations from outside the workplace rather than within it. The effectiveness of employers’ efforts can be questioned in this regard – and implications that for workplace actors (such as Equalities leads within HR departments, Diversity Managers, and EDI or ‘inclusion’ teams) legal compliance and the ‘business case’ for equality takes precedence over genuine commitment to progressive aims and practices.

The Equalities Act legislation should therefore be expanded to include provisions for negotiation and collective bargaining.

The role of workplace civil governance

Also within the workplace, staff networks – both formal and informal - organised along the lines of protected characteristics such as Black workers, disabled, or LGBT networks can provide an opportunity for worker visibility, voice, and engagement on these issues. In our research so far, we have found that these groups are often used as consultative bodies by employers during times of organisational change, and can offer feedback on and call for more inclusive workplace policies. A lot of their work encourages employer affiliation to or close working relationships with organisations offering reward or accreditation schemes, such as the Stonewall Workplace Equality Index. Civil governance has an increasing role in work and employment relations. There are now approximately 400 such organisations attempting to influence and shape employment in the UK. These types of schemes, however, can be subject to reputational and institutional pressures, and can be reluctant to challenge employers robustly on organisational change.

The missing link

Trade unions are generally more both willing and able to contest and challenge employers’ practices, and can be a more effective mediating agent than other civil society organisations. Where collective bargaining provisions are in place, this can have a positive impact on workplace equality, including narrowing the gender pay gap.

Though there are some progressive initiatives on bargaining for equality, these efforts remain piecemeal. While progressive employers – often in the public sector – already consult and work with trade unions on these issues, the voluntarist approach to bargaining in the UK results in the neglect of large swathes of the private sector, leading to an uneven adoption of good practice.

This complex hybrid of state, civil, and private regulation lacks both coherence and enforcement, and given the prevalence of the gender and ethnicity pay gaps, and the intersectional effects of the predominance of Black, Asian and ethnic minority women in precarious work, these measures are clearly not sufficient to address systemic inequalities.

Moving forward – policy and the equalities agenda

A more systematic review of trade union recognition that enhances the role of organised labour (as representatives of the workers these policies affect) is needed.

We suggest a national scheme which provides for statutory recognition for trade union equality representatives to be embedded within collective bargaining frameworks. This could ensure that workers' representatives are involved in the development of meaningful workplace equality policies and ensure their enforcement.

They could undertake training equivalent to managers or employer equality leads on aspects of equalities-related employment legislation, monitor adherence, and challenge employers if adherence is found to be lacking. These representatives would be well placed to be informed of and investigate any complaints or concerns about discrimination in the workplace, and challenge these in an institutionalised and collective manner not isolating the affected individuals. These initiatives in the UK would need a framework of support regarding training, auditing, and research, which the state previously developed – albeit in a limited manner – with the Union Modernisation Fund and Union Learning Fund during the last Labour government.

The OECD recognises the important role that workers’ representatives and collective bargaining processes play in designing and implementing equal pay structures, yet only a limited number of countries promote this. Strategies such as the equality plans in Spain can demonstrate the importance of formally bringing in trade unions as an essential part of the negotiation process. Spain is an emerging case study in the way a range of contemporary legislation and judicial decisions have placed trade unions in an important role in an employer’s development of equality strategies. There are some drawbacks related to coordination and timeframes, but it means that equality agreements and plans cannot be signed off by management unilaterally.

The adoption of these or similar strategies in the UK would ensure that equality can be embedded into many aspects of the employment relationship, resulting in workplaces which are more inclusive and less discriminatory, with people helping shape the decisions and policies that affect their working lives.

The Future of Work: Women's Experiences of Employment in Greater Manchester

Rosalind Shorrocks and Anna Sanders

Women in Greater Manchester face a range of barriers relating to their employment. As of December 2022, 72% of women in Greater Manchester aged 16-64 were in employment, compared to 80% of men. Women’s economic activity in Greater Manchester is also lower than the national level, where 75% of women aged 16-64 are in employment. Increasing women’s access to the labour market – and thereby utilising their potential – is key to raising productivity and economic outputs. Here, Dr Rosalind Shorrocks and Dr Anna Sanders draw on their collaboration with GM4Women2028 to explore how unequal pay and undertaking unpaid care affects women’s ability to participate in the labour market, as well as their career progression.

- Greater efforts should be made to support women’s progression and promotion in the workplace. Particular target areas are pay equality and consideration of childcare and unpaid care.

- Women with children under 5 expressed the most dissatisfaction with childcare arrangements, where unaffordable and inflexible childcare can pose challenges for women balancing employment alongside unpaid care.

- Employers should offer flexible working arrangements to women of all ages.

GM4Women2028 - background

To date, we have known little about women’s preferences and experiences of employment at the regional level. This is because most available data tends to focus on the national level.

In September 2022, a representative survey of women in Greater Manchester was conducted as part of a collaboration between academics at the Universities of Manchester and York, and a GM-based women and girls’ charity, GM4Women2028. Working with GM4Women2028 and other stakeholders, the What Women Want report identifies key areas of policy priority for women in the region. One of the areas identified was employment (and relatedly care).

Overall, we found that a considerable proportion of women in Greater Manchester are dissatisfied with their pay, with some demographic groups of women especially likely to be dissatisfied. Additionally, we found that unpaid care affects women across the life course. This has appeared to hinder women’s ability to participate in the labour market, as well as their career progression.

Perceptions of pay

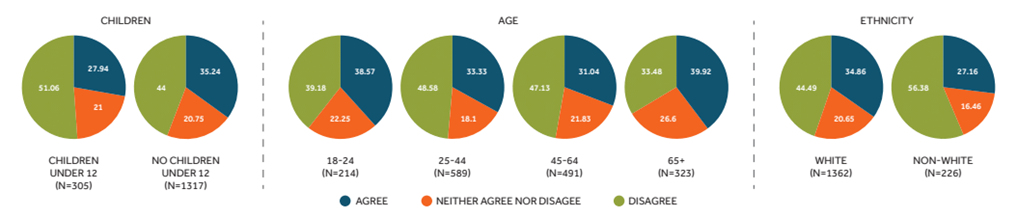

Women in Greater Manchester generally felt they were not paid enough relative to their experience and skills. Almost half (46%) of the women we surveyed disagreed with the statement, “Considering my qualifications, experience and skill level, I feel I get paid appropriately”, compared to just 34% of women who agreed with the statement. Notably, there were also differences between different demographic groups of women. Disagreement with the statement was highest among women with children under 12 (51%); women aged 25-44 (49%) and 45-64 (47%), and non-white women (56%).

Figure 1. Agreement and disagreement with “Considering my qualifications, experience and skill level, I feel I get paid appropriately”.

Care and employment

Another area that women responded to was unpaid care. Overall, 27% of women in Greater Manchester said that they provide unpaid care for children that they live with, and 17% of women provide unpaid care for children that they do not live with. Crucially, the impact of unpaid care on employment affects women across the life course. This includes older women who may fill the gaps in caring as grandmothers. One-quarter of women aged 65 and over said that they spend 0-19 hours per week caring for children they do not currently live with. This corresponds to another finding in our survey that grandparents are the most common form of childcare for women with children, used by 72% of women with children under 12.

Undertaking unpaid care also impacts women’s employment and career progression. 17% of women said that they had reduced their hours or gone part-time due to caring for children that they live with. This increases to 36% for women with children under 12. Additionally, 9% of women said that they had avoided taking a job with more responsibility due to caring for children that they currently live with. This increases to one-fifth of women with children under 12.

Childcare

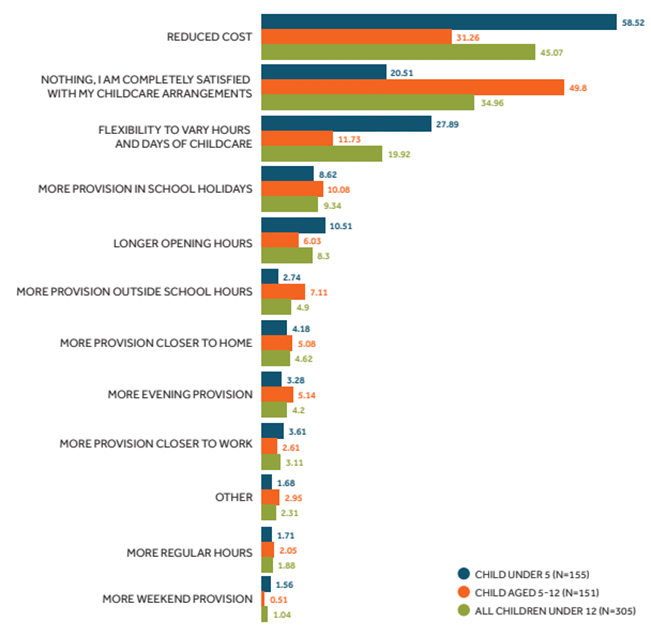

Evidence shows that flexible and affordable childcare can increase women’s participation in the labour market. Figure 2 shows what women with children would most improve about their existing childcare arrangements. There are clear differences between women with children aged under 5, and those with children aged 5-12. Half of women with children aged 5-12 were completely satisfied with their childcare arrangements, but this drops to just one-fifth of women with children under 5 (21%). Reduced cost was the most common improvement to childcare that women wanted to see, cited by 45% of women. This increases to 59% for women with children under 5. Also of note is flexibility to vary hours and days of childcare, cited by 20% of women (and increasing to 28% of women with children under 5).

Figure 2. Childcare arrangements used most by women in Greater Manchester.

Given there are greater concerns about childcare among women with children under 5, this suggests that there are issues with early years specifically. Currently, the UK has some of the highest childcare costs in the world. Unaffordable and inflexible childcare may pose challenges for women when it comes to balancing employment alongside unpaid care. Providing affordable childcare is especially important given the current cost-of-living crisis, which will likely mean that women will have less disposable income each month for childcare. Providing sufficient childcare may also help to relieve the burden on those filling the gaps in caring provision, such as older women.

Recommendations:

- Greater efforts should be made to support women’s progression and promotion in the workplace, with targeted measures for women with children and women from non-white ethnic backgrounds. The Greater Manchester Good Employment Charter could include additional commitments on progression and pay to address issues around women’s low pay and under-employment. The recommendations below which relate to reconciling unpaid care and work should also help address these issues.

- Flexible working arrangements should be available to women of all ages to enable the combination of work and unpaid care. We show women are undertaking unpaid care across the life-course - impacting total hours worked and career progression. Initiatives such as the Greater Manchester Good Employment Charter could help to ensure employers have a coordinated approach to flexible working.

- While local authorities have a statutory duty to ensure that there is sufficient childcare, responsibility for childcare policy currently rests with central government. The decision by central government in March 2023 to extend the early entitlement offer to children of younger ages is a welcome move. However, as early years provision is rolled out, central government must ensure that there is sufficient funding in the early years sector to match demand.

- Childcare policies should offer more choice to parents over how they can use their funded hours.

“Uncertain Futures: challenging intergenerational stagnation on inequality around work and retirement.”

Elaine Dewhurst and Sarah Campbell

The Uncertain Futures project has spent almost three years investigating inequalities in women’s mental and physical health, as well as economic well-being, experienced by older women (50+) with respect to work. These inequalities can stem from gender, race, age, disability, sexual orientation, migration status and socio-economic background. These inequalities can impact all areas of working life, from accessing work, to in-work conditions, and post-work retirement. Here, Dr Elaine Dewhurst and Dr Sarah Campbell outline their project findings and call for distinct and targeted policies to alleviate these inequalities and ensure a brighter future for women and work.

- The research findings contradict hopes that that these inequalities will reduce over time and younger women will have more positive experiences in older age. They identify an intergenerational stagnation when it comes to equality around work and retirement.

- Older women experience inequalities impacting their physical and mental health and their economic well-being in later life.

- Younger women are set to face similar deprivation in later life due to a failure to tackle inequalities and additional challenges particular to their generation.

Pension inequalities

The project has uncovered inequalities facing older women in our society around work and retirement. These inequalities are linked to their fragmented working lives, discrimination, low pay, zero-hour contracts, migration status, ill-health (both physical and mental), the menopause and disability.

The gender pay gap currently stands at 18% - which contributes to poor pension provision by lowering the contributions made by women over the course of their working lives. These inequalities have led to a gender pension gap of between 35% and 40% - with significant implications for health and financial well-being.

The ethnicity pension gap is even higher and more startling, starting at 24.4% and rising to 51% when factoring gender into the equation. These statistics indicate the combined effects of intersectional discrimination throughout women’s working lives and its profound effect on the quality of retirement.

Women’s retirement: expectations and realities

Our research indicates that older women have, overall, very humble aspirations for retirement, expressing desires to have financial security for housing and necessities, maintaining their standard of living, taking part in activities such as part-time work, hobbies, fitness and some travel, maintaining good health and spending time with family. However, our research also found that many older women cannot meet these basic aspirations in retirement and often felt a great deal of insecurity and uncertainty with respect to their futures. Women reported having limited financial security, expressed a fear of retirement due to reduced income and in some cases could not afford basic necessities. Rachel, age 60, expressed a desire to retire but indicated that she “couldn’t afford to retire”.

The situation was exacerbated by migration status, which often fragments working life more severely through lack of recognition of qualifications or difficulties in acquiring the language. Victoria, age 63, notes that because she arrived in the UK later in life, she did not know if “that’s going to be enough to retire on”.

Many older women resort to working in later life to supplement their incomes with accompanying risks for their physical and mental health. Gemma, age 59, is resigned to the fact that she might be “cleaning toilets ‘til I’m 85…I might be living in a treetop in the park”. Older women also contribute greatly as carers in society but worry about their own care in the future. Lois, age 56, describes this uncertainty well: “I don’t know who might be looking after me in the future after I’ve looked after other people. And how will that be paid for?”

The future of women’s old age, intergenerational stagnation

Whilst there have been significant positive changes in recent years, such as auto-enrolment for pensions, which should act to reduce some of the inequalities experienced by older women, these changes are offset by the often inadequate personal and material scope of these policies and other more temporal challenges, such as higher debt burdens and increased longevity. The experiences of older women today may match the experience of younger women in the future. We can see this intergenerational stagnation with respect to equality in a number of areas. The gender pay gap stands at 18% and over a working life will reduce the pension wealth of younger women by a staggering 28%.

Childcare costs are increasing exponentially forcing many women to fragment their working lives by either reducing their working hours or leaving work completely to offset these costs. The Government’s Equalities Office also found that the greatest barrier to women’s progression in the workplace (and thus higher pay and pension contributions) arose from the conflict between work organisation and caring responsibilities.

The situation of those from migration backgrounds, particular racial and ethnic backgrounds and those with disabilities, remain similarly challenged. Naturally, auto-enrolment of pensions has substantially increased the number of women who now have occupational pension contributions. However, many women fall outside of the scope of this scheme. This is because the scheme does not include those who are self-employed (approximately 1.6 million women) or those on lower pay (under £10,000) of which a higher percentage are women. There are also additional challenges facing younger women, which will impact them in older age. They are, for example, more likely on average to live longer and will need to save approximately 5-7% more for retirement than men. They may also carry the burden of higher mortgages or the cost of private rental accommodation both of which will expose them to significant risks in retirement.

Looking forward – policy recommendations

Many of the inequalities facing older women today will continue for younger women in the future. We have not learnt sufficiently from the past and history is set to repeat itself in the form of intergenerational stagnation on equality issues. It may be too late to undo some of the damage, but it is possible, through targeted policies, to improve the outcomes for women. We suggest here some policy changes - which would contribute to a lower pension gap for younger women and ensure that history does not repeat itself in its entirety:

- Pension contributions: the personal and material scope of the auto-enrolment scheme should be extended to capture more women and ensure more equitable contributions. We also support the introduction of a Family Carer Top-up - which would ensure that women would have a top-up to their pensions by the government when they take time out of work to care for family members.

- Flexible work: laws on flexible and hybrid work need to be strengthened and prioritised to reduce the fragmentation of working lives of women.

- Affordable childcare: naturally, the provision of affordable, flexible and accessible childcare would reduce the fragmentation of working life. Government should make wraparound childcare a key priority.

- Re-thinking GDP as a measure of progress: GDP measures only economic transactions related to the production of goods and services and ignores the voluntary contributions of many older women to the economy in the form of volunteer service provision, caregiving, neighbourhood-keeping and community activism.

With thanks to our academic contributors

Elaine Dewhurst is a Senior Lecturer in Employment Law at the School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Dawn Dowding is Chair in Clinical Decision-Making at the School of Health Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Kristian Fuzi is a PhD Researcher in precarious employment and pension planning at the School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester

Eva Herman is a Research Associate at the Work and Equalities Institute, The University of Manchester.

Mat Johnson is a Lecturer in HR Management and Employment Studies at the Work and Equalities Institute, The University of Manchester.

Stefania Marino is a Senior Lecturer in Employment Studies at the Work and Equalities Institute, The University of Manchester.

Miguel Martinez Lucio is a Professor of International HR Management & Comparative Industrial Relations at the Work and Equalities Institute, The University of Manchester.

Christopher Phillipson is a Professor of Sociology and Social Gerontology at the School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Debora Price is a Professor of Social Gerontology at the School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Rosalind Shorrocks is a Senior Lecturer in Politics at the School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Sarah Skyrme is a Research Associate at the School of Biological Sciences, The University of Manchester.

Holly Smith is a Research Associate at the Work and Equalities Institute, The University of Manchester.

Also:

Sarah Campbell, Manchester Metropolitan University

Heather Connolly, Grenoble Ecole de Management

Anna Sanders, University of York

Analysis and research on the future of work

Curated by Policy@Manchester

Read more and join the debate at blog.policy.manchester.ac.uk

@UoMPolicy

#Workingfutures

October 2023

The University of Manchester

Oxford Road

Manchester

M13 9PL

United Kingdom

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Manchester.

Recommendations are based on authors’ research evidence and experience in their fields. Evidence and further discussion can be obtained by correspondence with the authors; please contact policy@manchester.ac.uk in the first instance.