One Year On

Lessons from lockdown

Foreword

Professor Francesca Gains

One year ago, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus outbreak as a pandemic, with COVID-19 spreading in multiple countries around the world at the same time. A date that marked the start of an extraordinary year: of unimaginable restrictions on freedom of movement, unprecedented economic measures supporting vast swathes of the economy ordered to shut down, and the gravest threat to many citizens, vulnerable to a deadly new disease.

At the time of writing, on this salutary anniversary, there are grounds for optimism, that with the success of vaccination development and a phenomenal vaccination rollout programme there is the realistic prospect that many of the restrictions and privations of the last year may slowly be lifted and some semblance of normality returned. Over the last year, the impact of the pandemic has both revealed – and will further entrench – significant inequalities in who is affected by COVID-19, economic consequences, and the likelihood of recovery.

In summer 2020, Policy@Manchester published Lessons from Lockdown, bringing together research insights from across The University of Manchester as policymakers and citizens grappled with the radical changes to the way we lived our lives. Since then, our academics have continued to write about the issues the pandemic has highlighted and the policy messages this research highlights.

Of the blogs we published in the last seven months, three main themes emerged. Firstly, research insights with relevance to addressing inequalities in both communities of place, and communities of identity, particularly communities who face racial discrimination. Secondly, the consequences and implications for the delivery of healthcare to address health inequalities and to achieve better integration of health and social care. And thirdly, policy messages relating to the social, economic and behavioural implications of new routines for tackling climate change.

So as the schools go back, the vaccine rollout moves into the next phases, and a recovery period begins, this collection is a snapshot in time, sharing some of the key policy recommendations to build back better and build back fairer.

March 2021

Local Communities

Lockdown has made us re-evaluate the way we interact at work, school, and in everyday life. It has prevented us from carrying out our normal tasks, routines and pastimes as we are faced with restrictions on gatherings, the closure of schools and businesses, and travel bans. This has led the general population to reside in their local areas, creating a greater dependence on strong local communities which, during the pandemic, have become vital sources of support, comfort and light in a time of uncertainty and struggle.

The following blogs written by experts at The University of Manchester, draw upon local and national evidence to assess different topics and potential issues faced within our local communities.

- Teenagers' experiences of life in lockdown and lessons for COVID-19 recovery plans by Dr Ola Demkowicz (Manchester Institute of Education), Dr Emma Ashworth, Dr Terry Hanley (Manchester Institute of Education).The authors argue that recovery plans need to focus on mental health and wellbeing – especially for young people. Policy must include support and investment in schools and communities, resources for staff, and a reflection on the current education system and what it asks of young people.

- Building back better: Rethinking urban futures with children and young people by Dr Deborah Ralls, who states that children and young people need to be included in decision-making and viewed as key stakeholders in the world by creating initiatives such as urban learning labs and urban apprenticeships that brings children and policymakers together.

- COVID-19 and social inequalities: Developing community- centred interventions by Professor Chris Phillipson, Dr Sophie Yarker, Dr Luciana Lang, Dr Patty Doran, Dr Mhorag Goff, and Dr Tine Buffel (all from Manchester Urban Ageing Research Group). They discuss the need for all voices to be heard through a range of community-centred policies that utilise the skills and knowledge of local residents; recruit community advocates; and include diversity in COVID-19 pandemic management teams to ensure that all members of ethnic minority, low-income, LGBT+ and ageing communities are represented.

- How to support refugees and asylum seekers’ health and wellbeing by Jo Biglin, who argues that legislation is needed to protect community gardens, allotments and green spaces. This includes a legal requirement for councils to provide free, open and easily accessible community spaces aimed at improving the mental health and wellbeing of marginalised and vulnerable groups.

Teenagers' experiences of life in lockdown and lessons for COVID-19 recovery plans

Ola Demkowicz, Emma Ashworth, Terry Hanley

Originally published 21 October 2020

This year, teenagers have found themselves restricted to their households, unable to see friends. Exams were cancelled, followed by an exams fiasco that caused widespread confusion and distress. Beginning new programmes of study has also come with new health concerns, including quarantining of school bubbles and lockdowns in university halls of residence, amidst shifts to virtual learning. The job market continues to dwindle, and initial evidence suggests that employment issues are hitting young people particularly hard.

An emotional rollercoaster

In The TELL Study (Teenagers’ Experiences of Life in Lockdown), we explored how UK-based teenagers aged 16 to 19 years subjectively experienced lockdown, with an emphasis on wellbeing and coping. In May 2020, 109 individuals wrote about their experiences, describing what lockdown looked like for them, what it felt like, and how they were managing it.

They described how lockdown brought many intense, difficult feelings. They experienced major changes to daily life, losing their routine and feeling isolated from friends – all of which was emotionally difficult. They also expressed fear about contracting COVID-19, both for themselves and their loved ones (and indeed in some cases, have lost family members).

“I have been feeling a wide range of emotions throughout the lockdown so far, my main emotion has been sadness.”

Teenagers told us they were working on taking care of themselves, using various strategies, although this wasn’t always easy. However, some also described feeling positive emotions alongside more difficult ones, or even felt okay overall. Many described feeling relief in lockdown, as the normal pressures of daily life had been removed and they were able to take the time to explore themselves and how they wanted to spend their time.

Sacrifices and uncertainty

The teenagers in our study told us that their lives had changed dramatically, and they felt they were giving up a lot, including “normal” teenage experiences: exams, hanging out with friends, the last day of school, prom, travelling. They felt these were important sacrifices but were still upsetting.

They described a great deal of uncertainty about the future. They had lost control of their grades, missed important activities that could boost CVs and personal statements, and worried about the future of the job market and the potential impact for their employment opportunities.

“I really wanted to do a degree apprenticeship instead of going to university, but my chances of doing that have reduced to almost impossible because so many companies can’t afford apprenticeships and the job market is so busy due to so many people losing jobs.”

Teenagers have been overlooked

Whilst teenagers have made enormous sacrifices this year, they have routinely been overlooked in decisions and villainised by the government and media. In our study, teenagers described frustration with the government’s handling of the pandemic, including concerns that their age group had been overlooked, with little guidance on how their education settings could support them or reduce transmission.

What can we do?

Recovery plans need to prioritise mental health and wellbeing, provide certainty where possible, and include teenagers in decision-making. Below we reflect on how this could be achieved.

Prioritise mental health and wellbeing: Schools, colleges, and universities need to be able to focus on mental health and wellbeing. Everyone is coping differently, and teenagers therefore need multiple support options. For some, normalising the messiness of the situation may be helpful in group situations like classrooms and clubs, while others might need more personalised support from teachers and mental health and wellbeing professionals such as counsellors. At a policy level, this requires proactive support and investment in resources in schools and communities, including support for staff, as supporting teenagers at this time will likely be challenging.

In the short-term, this may clash with a perceived need to “catch up” on lost learning – policymakers could reduce some of the academic pressures contributing to that, such as reducing the pressure of exams. Policymakers and local authorities should work with education settings and teenagers to identify local wellbeing needs and ensure that there are support and resources available to work towards meeting these.

In the long-term, the lockdown provides a critical opportunity to reflect on the demands of education and daily life for teenagers. It is concerning that many teenagers experienced relief in lockdown, highlighting how much we normally ask of them. We must consider how our education system can better meet teenagers’ needs without creating too much pressure and, critically, must ensure that this pressure doesn’t worsen post-lockdown in a rush to catch up.

Provide more certainty: This year, there has been limited communication for teenagers about exactly what is going to happen, how it will happen, and why it will happen that way. Though there is a need to be reactive to the pandemic, where possible decisions need to be prompt and transparent, with clear communication and explanations for teenagers. Early, clear decisions will reduce uncertainty and give teenagers a greater sense of direction and control. Effort needs to be taken to create normality where possible, balancing their developmental need to socialise with peers and be independent with steps to restrict the spread of COVID-19.

Where there is uncertainty, teenagers may benefit from greater support to help them prepare for different eventualities. For example, increased career support provision could help teenagers prepare for emerging education and employment issues and create realistic goals to work towards.

Job schemes for teenagers and young people are especially important given that employment issues seem to be hitting younger people particularly hard, and the uncertainty of this is already causing distress. The initial “Kickstart” campaign could offer value, but is only a short-term solution for those at greatest risk, and is a blanket national approach with no capacity for localised tailoring and innovation. Greater investment and strategising towards youth employment will not only be valuable economically but also for mental health and wellbeing, to ensure that our teenagers and young people have hope and a feeling of direction for the future.

Involve teenagers in decision-making: We need to take clear steps to show teenagers that we value them and are taking their needs seriously. This includes much greater efforts to involve teenagers in policy and provision decisions. Nationally, there is a need to work with and communicate with teenagers in making decisions that affect them and support local communities to offer this in their own contexts (see the #iwill campaign to see effort to centralise young people’s voices). Locally, authorities should focus on understanding emerging local needs and involving young people in their decision-making – for instance, Manchester City Council’s new Shadow Executive of young people is a positive step and will be key to involve them in COVID-19 recovery planning. It may be valuable for other local authorities to consider ways to adopt or extend similar approaches to consistently involving young people in their decision-making processes.

Building back better: Rethinking urban futures with children and young people

Deborah Ralls

Originally Published 27 October 2020

Building back better has its roots in disaster recovery. It advocates a determination to do things differently, to avoid a return to ‘business as usual’ and to focus instead on models of long-term economic and community resilience that prioritise wellbeing and inclusiveness.

Building solid foundations through active citizenship

It has long been acknowledged that we live in a rapidly changing world, but COVID-19 has accelerated this change and presented accompanying challenges that are beyond our imaginations. Yet the pandemic has also given rise to hope that societies can use the current situation as a catalyst for change for a more inclusive, socially just society.

Building back better for economic and community resilience requires a solid foundation that can futureproof inclusive towns and cities and improve citizens’ wellbeing. There is an increasing recognition that our understanding of the socio-economic functioning of society, and the active role that we can play in it, is shaped from childhood. However, particularly in the current climate, CYP’s fundamental right to participate in the matters that affect them is often overlooked. We need initiatives that can support young people’s efforts to safely and effectively act as agents of change beyond the pandemic, to actively participate in shaping responses, and to be meaningfully included in all aspects and phases of the response as existing, active citizens. It is clear then, that as societies everywhere undergo transformation, if we are to build back better, approaches to education must also change.

Experts are warning of the catastrophic and long-lasting impact of the loss of economic and social opportunities for young people as a direct result of policy choices made during the pandemic: “We’re talking about this generation not being able to contribute to a well-functioning economy … The implications couldn’t be more far-reaching for us all.” COVID-19 has brought into sharp relief that governments need to do more than deal with immediate threats; they must actively plan for our shared futures.

Engaging our youngest citizens as active partners in urban policymaking decisions and taking their opinions and concerns seriously, can contribute to individual wellbeing and self-esteem whilst also building a shared, intergenerational awareness of urban challenges and possibilities.

A rapidly changing world requires new approaches to urban education policy that are about more than classroom-based learning and a focus on individual academic achievement. Now, more than ever, it is vital that we remember that education is at the heart of both personal and community development. There is a need for education policy to focus on learning environments and on new approaches to learning for greater justice, social equity and global solidarity.

The city/town is a classroom

A large number of urban places are deliberately choosing to change the way they view education by identifying and developing a myriad of learning opportunities available beyond the school gates. Such an approach eliminates the limitations of learning within the school, turning the town or city itself into a classroom with a rich, diverse curriculum – a place of possibility to be explored by CYP.

It is vital that a wide range of CYP from all areas can regularly contribute to policies to improve their town or city. However, building back better requires CYP and policymakers to develop mutual knowledge, dialogue and joint ways of working where CYP must be considered as the experts in their own lives.

In order to address these issues, urban education policy can set out to develop a curriculum that is ‘more than school’, offering CYP regular, ongoing opportunities to ‘learn to do’ urban decision-making and to work collaboratively to build back better with a range of people from outside their local neighbourhood. Education policy needs to be redefined to generate collaborative learning opportunities where i) children and young people develop their knowledge related to urban decision-making processes and ii) policymakers learn about young people’s wide range of lived experiences, gaining an insight into young citizens’ hopes, fears and areas of expertise.

Learning to live and do together: building back better

Education is fundamental to any collective attempt by towns and cities to build back better for the common good. CYP have the right to a broad and varied education that encourages respect for their own and other cultures, and the environment. That right should start with the close-at-hand world of their hometown or city, via an approach to education policy that helps today’s CYP build the relationships, skills and knowledge they need to be active citizens and urban decision-makers.

One way of starting a collective approach to urban education would be through increasing awareness of the varied day-to-day lives of CYP through the development of urban learning labs. Labs located across diverse urban communities can be used to bring together CYP and urban policymakers from different areas to develop shared ideas for an inclusive town/city. These spaces give CYP a place to express their views in a variety of ways of their choice, offer CYP freedom of expression and the right to participate in the matters that affect them so that they can contribute collectively to improving policies for the benefit of all citizens.

In order to futureproof an inclusive town or city, urban education policy needs to improve participatory processes based on co-responsibility and active citizenship. It is essential for both CYP and policymakers to experience and understand the town/city in its many dimensions. To build back better we need to give CYP the ‘Right to the Town/City’, a form of urban apprenticeship beyond the school. Such an apprenticeship would position CYP as urban experts, who teach other CYP and adult professionals about the area where they live, its challenges and possibilities. Learning would give CYP and policymakers the opportunity to learn from others about lived realities in different areas, so as to better understand the town or city in all its diversity. Such participatory processes enable a shared understanding of what it means to build back better, developing co-responsibility for rethinking urban futures – with, not for, our children and young people.

COVID-19 and social inequality: Developing community-centred interventions

Chris Phillipson, Sophie Yarker, Luciana Lang, Patty Doran, Mhorag Goff, and Tine Buffel

Originally published 22 February 2021

To date, communities who have been affected most by COVID-19, have not been included in debates on how to limit the spread of the virus. Questions also remain about reaching out to these groups and ensuring the engagement of communities in the development of future policies regarding the pandemic. As a result, there is an urgent need for what might be termed a ‘community-centred’ model, as developed by Public Health England, to work alongside the implementation of mass vaccination and reinforce non-pharmaceutical interventions.

The pandemic has posed particular difficulties for many low-income neighbourhoods, at a time when they had already been weakened through job losses and reduced funding from local government. Neighbourhood-based inequalities have deepened in the context of COVID-19, with people (of all ages) living in the poorest parts of England and Wales dying at twice the rate from the disease compared with those in more affluent areas.

Working directly with communities

To create a community-centred response and adopt methods of co-production in low-income communities, using the skills and knowledge of local residents will be essential. These can: deepen our understanding of attitudes towards COVID-19 – especially amongst groups experiencing various forms of social exclusion; assist dissemination of advice and messaging about protection from the virus; and challenge negative stereotypes attached to particular groups by emphasising the skills and knowledge which they can bring to support work to control the virus.

Working with ‘informal’ and ‘formal’ leaders within communities will also assist in the uptake of pharmaceutical interventions and encourage people to stay as safe as possible. It should also help in stopping the spread of misleading/false information about vaccines through social media. One example of the importance of community leaders concerns the role of Imams, who in January 2021 delivered sermons in mosques across the UK which sought to reassure worshippers about the safety and legitimacy of COVID-19 vaccinations and remind them of the Islamic injunction to save lives. The move came amid evidence of anxiety within Muslim communities about the safety of vaccines, and concern about slow take-up in some parts of the UK.

Experts also suggest that COVID-19 pandemic management teams should incorporate community members into the planning, response and monitoring of standard operating procedures. They emphasise the importance of disseminating this work through the various networks within communities to ensure maximum support. Ensuring diversity in the membership of management teams is essential, especially regarding members of minority ethnic communities, and workers in low-income communities.

Additionally, building on existing networks and neighbourhood organisations will be vital in developing community-based interventions. Food banks, local businesses, and libraries are essential sites for conveying information and supporting older people during the pandemic. These can be complemented through support from existing organisations, for example those linked with the UK Network of Age-Friendly Communities.

Recruiting ‘community advocates’ for those who may be unable to ensure their voices are heard will be an important approach to consider – particularly for those who may be vulnerable to having their interests overridden at times of crisis. Advocates could be drawn from existing organisations, for example local Age UK branches, Good Neighbour and befriending groups and equalities organisations such as the LGBT Foundation. However, this would require resourcing to support training and financial assistance to advocates, an issue which might be considered by central government as well as local authorities.

Developing long-term community-centred policies

Some longer-term priorities for community-centred policies also need to be considered. Any strategy to combat the pandemic has to be rooted in addressing the multiple forms of deprivation affecting many communities in the UK. These, as the evidence shows, are drivers for transmission of the virus, notably through overcrowded households, with household members employed in high-risk occupations passing the virus across generations. Future action should be placed within a wider context of ‘community renewal’. COVID-19 has preyed on neighbourhoods damaged by cuts to basic services and social infrastructure, lack of investment in housing, and the rise of precarious forms of employment.

However, renewal must also come from ‘below’, with the strengthening of neighbourhood-based organisations. This will be especially important given the impact of three lockdowns in reinforcing social isolation amongst groups within the older population, individuals from the LGTB+ community, people with learning disabilities, and others whose networks have been depleted through losses arising from COVID-19.

COVID-19, as numerous reports have made clear, has exposed and exacerbated longstanding inequalities affecting BAME groups in the UK. Racism and discrimination also play an important role in this regard. Much of this was predictable given available knowledge about poverty, co-morbidities, poor quality housing, and low incomes, affecting many of those in South Asian and other minority ethnic communities. The question is why there was a failure to co-ordinate preventative forms of community-centred working with BAME groups from the beginning of the pandemic. Such targeted work, involving community leaders wherever possible, will be essential over the medium and longer term. However, this type of initiative will require additional sources of funding to support what are financially constrained organisations even in ‘normal times’.

Finally, COVID-19 has proved catastrophic for people in residential care. By mid-January 2021 in the UK, one-third of fatalities (32,000 people) were care home residents. This is an extraordinary figure which indicates a systemic failure to safeguard a highly vulnerable group.

Bold thinking is needed by the research and policy community about the future of residential and nursing home care: challenging rather than colluding with current models of care. Privatisation has proved a flawed model; but the public or not-for-profit sector does not provide a straightforward solution either. The way forward must certainly be to ‘downsize’ from ‘industrial scale’ care, potentially looking at placing the management of homes within a local authority framework. Crucially, all homes should be embedded in their surrounding neighbourhood. Developing viable models which provide some degree of protection for people will be challenging but the impact of COVID-19 has confirmed the urgent need for major reforms of the health and social sector, for this and many other reasons.

How to support refugees and asylum seekers' health and wellbeing

Jo Biglin

Originally published 10 August 2020

It’s nothing new to point out that local authorities across the country are struggling to support refugees and asylum seekers. Dispersal policies see asylum seekers disproportionately housed in some of Britain’s most deprived areas, and local authorities receive no extra funding to cope with supporting them. Greater Manchester consists of some of the most deprived areas in the UK, yet the region has some of the UK’s largest populations of dispersed asylum seekers. In 2018 Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester, wrote to the Home Office urging it to reconsider its dispersal policies, as a result of pressure from local councils to express the mounting struggle relating to shortages in resources that was – and still is – affecting regions across the North.

The Home Office has shown no sign of revaluating its position on the dispersal system. Consequently, local authorities continue to struggle to support refugees and asylum seekers. Exacerbating this are ongoing increases in restrictive policies relating to asylum seekers’ access to welfare and services such as education and the NHS. Furthermore, cuts are being made to integration and enrichment programs; for example, free English as a Second or Foreign Language classes are no longer funded by the government.

Mental and physical wellbeing

Refugees often experience a range of mental health issues, resulting from the trauma of displacement and events that led up to displacement, and these can be compounded by new experiences within the UK. Refugee and asylum seekers experience a number of barriers to mainstream health care, including the dispersal systems moving them throughout the country, and a lack of awareness of entitlement. Therefore, the importance of understanding places of restoration and healing for refugees and asylum seekers is imperative to the improvement of government policies concerned with such issues.

My research focused on an urban allotment run by a charity in Manchester that aims to provide practical, emotional, and social support and advocacy for refugees and asylum seekers. Findings suggested that the wellbeing of the participants was improved by attending the allotment because it alleviated feelings of social isolation and loneliness. It was somewhere to engage in familiar and pleasurable activities and positive nostalgia – as many refugees come from agrarian backgrounds – and was a place to keep physically active and busy, given people seeking asylum are not permitted to work. Finally, the act of nurturing a plant to bearing fruit acted as a metaphor to nurture the self and others.

A new policy response at the local and national levels

This research highlighted how this urban green space had a significant impact on the health and wellbeing of refugees and asylum seekers. In the wake of continuing restrictions on asylum seekers’ access to welfare and services, new worries about the potential impact of a no-deal Brexit on funding, and the impact of COVID-19 on local authority budgets, it is easy to see how local authorities might struggle to prioritise something like developing an allotment project over more basic support systems.

While understandable, improving the health and wellbeing of vulnerable people can happen if decision-makers, authorities, and politicians involved with and responsible for the design, planning, development and maintenance of urban green space can work with what Manchester already has – green space. Manchester has a comprehensive green and blue infrastructure strategy and action plan from 2015 – 2025 that recognised the importance of urban green space for the development of the city. The plan recognises where urban green space had the potential to have a positive impact on the city, from the large scale, such as economic growth and investment, to the local level of improving communities’ health and wellbeing. Overall the aim is that ‘by 2025 high quality, well maintained green and blue spaces will be an integral part of all neighbourhoods’. While the plan does include some discussion of community growing spaces, there is no mention of how these, or any sort of green space, can be targeted at specific marginalised groups.

This is unfortunate, as in addition to the discussion presented here on the impact on refugee and asylum seeker populations, there is also evidence of the role growing space can play in improving the lives of other marginalised groups such as people suffering with mental health illnesses and adults with learning disabilities. What’s more, there is also discussion of the positive impact school and community grow gardens can have on children from all backgrounds, but particularly those from deprived backgrounds.

On a national level, the research I have conducted demonstrates how important it is for policymakers to recognise the value in enrichment projects such as an allotment, with the ultimate goal of attaining adequate funding for local authorities and charities so that they are able to provide these services.

More specific policy asks include legislating for a minimum area of open and accessible green space per thousand people, and for councils to be required to provide free community growing spaces. Allotments have extensive legal protection and it is a legal requirement that they are provided by councils. However, this legislation is insufficient to cover the importance of allotments tending to asylum seekers and refugees. Despite the legal requirement to this, there are extensive waiting listings for access to an allotment plot; a report in 2010 estimated a waiting list of around 40 years in some areas. Furthermore, there is a cost associated with renting a plot, reducing the accessibility for many marginalised groups.

Community gardens are not protected by statutory law. Therefore, legislation is needed to protect community gardens/allotments, alongside legal requirements for councils to provide free, open, and easily accessible community growing spaces. Additionally, councils must be required to demonstrate that they are targeting specific user groups and educating them on the benefits of using green space and community gardens and encouraging these groups to use such facilities.

COVID-19 has flung into focus the importance of green and outdoor space to partake in physically distanced exercise, and in doing so, has exposed further inequalities within our society. Those living in small flats in deprived urban tower blocks, with no access to private gardens, also had poor public green space provision. Given the known benefits of outdoor/green space to our mental as well as physical wellbeing, this is something that will lead to health inequalities. The original COVID-19 lockdown guidelines permitted time in an allotment as a form of exercise, with members of the same household, and where physical distancing was possible. Thus, legislation to provide and protect community gardens/allotments could have had a significant impact on the health and wellbeing of marginalised communities in unprecedented times of need.

The Health and Care System

The health and care system, now more than ever, has become a focal point for policy improvements and reform. Over the past few years, the way in which the NHS and the services it provides are viewed, has changed. A large and ageing population with diverse backgrounds and needs, has led to increased demand and growing strain on the system. Due to the extreme pressures thrust upon it by COVID-19, there is a greater need to produce positive outputs that are accessible for all.

While there are infinite ways to reform policies around the nation's health and care system, we are faced with limited resources, funding and time. Therefore, policy asks and recommendations put forward need to bear the greatest impact for the short and long term.

This section features three blogs focusing on varying areas of the health and care system.

- Follow the science by Martin Yuille and Professor Emeritus Bill Ollier. They argue that public policy needs to be led by science and evidence which encompasses all governmental departments both at a national and local level, in order to focus on the health of the nation rather than the health and care system.

- Inequalities in ageing: Health disadvantages amongst ethnic minority groups by Dr Ruth Watkinson (Institute for Health and Policy Organisation) and Dr Alex Turner (Health Organisation Policy and Economics Group).The authors examine the need to improve ethnic health inequalities in ageing, by ensuring adequate representation in health research and equity of local health services based on individual ethnicity needs. They state that policies must knock down health barriers, reduce socially deprived ethnic minority neighbourhoods and educate medical staff to tackle the underlying systemic racism that leads to health disadvantages.

- The Health and Social Care system under strain: Rethinking integration policies in the post COVID-19 era by Dr Marcello Morciano, Dr Kath Checkland, Professor Matt Sutton, Dr Jonathan Stokes. The writers put forward the case for a joined-up health and care system across the country to create an integrated primary care system for all, arguing the integration must be carefully considered and planned to take advantage of the resources, experience and support at hand.

Policy@Manchester along with our leading experts has looked further into primary care and integrated healthcare services in a publication called On Primary Care: General practice, pharmacy, workforce.

Follow the Science

Martin Yuille and Professor Emeritus Bill Oliver

Originally published 23 June 2020

After the pandemic, which window of opportunity will open widest for far-reaching innovation and experimentation in public policy reform? If there is one window that cannot be shut back down, it surely relates to public policy in the field of health.

We distinguish ‘health’ from ‘healthcare’; health is a state we all wish to have, while healthcare is an intervention we all wish will end as quickly as possible.

Post-COVID-19, it will not be simply a matter of improvements to stockpiling of PPE, increased provision of ventilators or intensive care beds, or capacity for population-wide testing or large-scale contact tracing. There are deeper issues at play, going right back to basic definitions of ‘health’.

This broader issue of health has to be tackled afresh, because what makes COVID-19 such a problem is that, while it is a mild disease for those who are otherwise healthy, it becomes a killer disease for those with underlying conditions. This is also frequently the case with other respiratory infections like influenza. Continuously improving population health by tackling those underlying conditions is the best defence there can be against the next viral pandemic. That is what public policy now has to put right.

The underlying conditions that make COVID-19 into a killer disease are themselves pandemics. They include chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Prevention does not mean improving treatment of these conditions, but reducing the risks that we all face of getting them. Those risks are well-known: obesity, for example, was identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a global pandemic years before COVID-19 came along. It affects not only high income but also middle- and low -income countries. In North Korea, obesity (BMI over 30) affects 6.8% of adults. The WHO has coined the term ‘globesity’ to refer to the problem.

If we ‘follow the science’, then continuous improvement of population health requires us to think again about how public policy can be used to combat obesity, insufficient physical exercise, and social isolation. Public policy has, so far, failed. Healthcare policy is not the issue in the first instance. By the time we need healthcare, we have missed the opportunity to prevent ill-health. The direct issues relate to food and agriculture policies; transport, housing and planning policies; and cultural and community policies. The indirect issues include education policies, economic and business policies, and even foreign policy (think of chlorinated chicken or hormone-enriched beef).

Improving population health as a goal in itself and as protection against the next new viral epidemic thus encompasses public policy as a whole, if we are to follow the science. WHO has expressed the need for ‘health in all policies’ so as to fight against common chronic conditions. This would put health on the agenda of every department of national and local government.

However, this does not go far enough. Health should not merely be on the agenda. It has to become the agenda itself. In other words, health has to become the purpose, the organising principle, the raison d’être of government and of governance. If we do not follow the science, we will be left with the consequences of ever-increasing levels of diabetes, heart disease, cancer, depression and anxiety. Much of the £152.9 billion needed in 2018/19 by the NHS goes on treating these conditions. Then there are the non-NHS costs of the consequences of this ill-health. Public Health England has calculated that the financial costs to individuals, employers, the NHS, the government, and to the whole English economy to be between £147 billion and £185 billion per annum. This corresponds to about 11% of GDP for the UK as a whole. Despite all this cost, without change, we shall still be left at the mercy of the next pandemic.

Government change

Health is not the ‘absence of disease’: we endorse the argument that it should be defined as the status we each have when our needs are optimally satisfied.

Applying this definition in policy reform, a Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) should have direct responsibility for population health and should have the role of coordinating action on health across all departments. The Department of Health becomes the Department of Healthcare. MHCLG seeks optimal housing provision. BEIS ensures that employers provide optimal rest and exercise for employees – as well as safety at work. And so on.

Part of the DPM’s coordination can be delivered via the National Risk Register that was introduced in 2008 to list, monitor and mitigate significant risks. Flu is on the register. So are emergent infectious diseases. But obesity, for example, is not – despite the recommendation of the Chief Medical Officer. All the modifiable risk factors for the common long-term conditions need to be on the national and community level risk registers. The register is a good tool for defending communities from floods. It needs to defend them also from the pandemic in chronic conditions. Of course, this requires a government that takes risk reduction seriously. The recent depletion of national PPE stockpiles indicates that this cannot be taken for granted.

In addition to such institutional changes in our governance, we also need community and technological change.

Community change

Britain’s first-ever Public Health Minister, Tessa Jowell, laid out a vision in 1998 for improving the health of the population that saw stakeholders – including communities – agreeing to work together. Moving from vision to practise is never easy, and the first major attempt at improving population health in 2008 relied not on stakeholder agreements, but on a conventional service approach, with the introduction of the NHS Health Check.

This service has persisted for over a decade but is at risk of becoming solely triage for patients. However, it can still provide a platform for reforms that would promote the health of the population via stakeholder agreements and that would elevate individuals and communities from passive recipients of a service into citizens and organisations who are engaged and involved in their own health and that of others.

One idea is to convert the typical practise nurse who performs health checks into someone who also undertakes community development work. Citizens coming in for checks would be encouraged not only to improve their own health but also to work for their community on such goals. Some citizens would then become health champions. The rapid recruitment of 750,000 volunteer champions of the NHS at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that there are many people who would want actively to aid their fellow citizens’ in preventing disease.

Imagine health champions (recruited at an NHS Health Check and supported by the nurse/community development worker) who are members of football fan clubs. They might undertake to improve their fitness and lose weight alongside their fellow fans at the club (regardless of whether they have had a health check). The club is encouraged to support this because the fans want to bring their families and friends along too. Thus, the health check has become a tool simultaneously for improving health, for community development, and for building a local business.

Technological change

The technical business of health improvement is ‘risk reduction’. This means I need to know, as quickly and as precisely as possible, that I am being successful in minimising my risk factors for the common long-term conditions. I need regular testing of my ‘risk biomarkers’ with my test results stored safely. These risk biomarkers are simply molecules in our bodies where a change in structure or concentration is robustly associated with decreasing risk of, say, diabetes.

Little research has been done on such risk biomarkers because work on prevention has been so feeble. However, with the right prevention infrastructure in place, the innovation required should be quick and straightforward. Unsurprisingly, this infrastructure is precisely what is needed to prevent a disaster when the next pandemic strikes. It comprises a national health data management system comparable to what was being built up until 2010 by the NHS Connecting for Health project, plus a biobanking system comparable – but larger – than the UK Biobank project started in 2005.

Nearly all governments around the world have decided that they need to say that they are following the science in dealing with COVID-19. From the point of view of the way that public policy rationales change over time, the new reliance on evidence makes a welcome change from reliance on either dogma or fantasy. The challenge for public policy thinkers will often be a need for them to brush up on their knowledge of areas of science that are key to public policy, areas such as epidemiology.

Inequalities in ageing: Health disadvantages amongst ethnic minority groups

Dr Ruth Watkinson and Dr Alex Turner

Originally published 1 February 2021

Both the direct and indirect consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic have hit those from poorer areas and ethnic minority groups hardest. These devastating impacts have come on top of long-standing health inequalities, which had already been exacerbated by years of austerity. In February 2020, a damning report into health inequalities in England found that the previous trend of steady increases in life expectancy was already faltering, and that life expectancy in the poorest communities was actually falling for the first time.

More shocking still, we simply do not know whether or how life expectancy trends have differed between ethnic groups over the same period. There are no estimates available because ethnicity data is not recorded across many administrative systems and there is poor representation of ethnic minority groups in national datasets. This negligence is a form of institutional racism, and allows health inequalities by ethnicity to largely go unmonitored and therefore unchecked.

What does our study show?

Our recent study used the national GP patient survey to describe ethnic heath inequalities amongst older adults (aged 55 plus), an age group that is becoming increasingly ethnically diverse. As populations are ageing and more people are living for many years with multiple chronic health conditions, supporting healthy ageing has become an important focus of healthcare and health research. Health inequalities amongst older adults are a particular concern, as the effects of repeated disadvantage accumulate over the course of life, thereby widening inequalities.

Drawing on responses from over 150,000 older adults who self-identified as belonging to ethnic minority groups (as well as over 1.2 million who identified as White British), we found wide inequalities in health-related quality of life, a measure of day-to-day physical and mental health. There were particularly striking disadvantages for some groups; the average health of 60-year-olds belonging to Gypsy or Irish Traveller, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Arab groups was similar to that of an average 80-year-old.

Importantly, we found wide variation in outcomes between different ethnic minority groups, including those that are often combined in statistical analysis. For example, considering Asian ethnic groups, health-related quality of life was substantially worse amongst Bangladeshi and Pakistani older adults than amongst those of Indian, Chinese, or other Asian ethnicities. This highlights the importance of collecting detailed ethnicity data and including sample sizes that allow analysis of each group individually rather than using broader and potentially unhelpful groupings such as ‘Asian’ or ‘BAME’, which can mask inequalities.

Looking at what might drive these inequalities, we found people from most ethnic minority groups were more likely to have more long term health conditions than their White British peers. With good treatment and support, health conditions don’t inevitably lead to declines in quality of life. However, we found people from ethnic minority groups tended to face additional disadvantages in the healthcare and support they received. Older adults from some ethnic minority groups were more likely to report poor experiences at their GP surgery. Similarly, those from almost all ethnic minority groups were much more likely to say they lacked confidence managing their own health and didn’t receive enough support from local services. These results suggest some NHS and other local services are failing to meet the needs of all individuals equally, adding to growing evidence of institutional racism.

Finally, consistent with many other reports and evidence of pervasive structural racism across British society, we found that older adults from almost all ethnic minority groups were much more likely to live in socially deprived neighbourhoods; further contributing to inequalities in health.

What policy changes are needed?

Over recent years, there have been many reports into discrimination and ethnic inequalities across settings from education and workplaces to the criminal justice system and public health. Each report makes recommendations but few have been meaningfully implemented. The recent Lawrence Report focused on the impacts of the pandemic on ethnic minority groups. It concluded that a wide-ranging national strategy to reduce health inequalities is urgently needed, and must be developed collaboratively with representatives from ethnic minority communities. The government needs to respond with clearly specified and ambitious targets, which must be backed up by legislation, ministerial accountability, and funding.

Progress and accountability will rely on better data, so this must also be a priority. Routine monitoring of ethnic inequalities in health and its determinants as part of performance measurement of local health systems should become commonplace, as has occurred for deprivation-related inequalities. Without this, the success of enacted policies will be difficult to judge.

Equity should be central to quality assessments of all health and wider local services. Where services are not working fairly, it will be important to understand why. Investment and community co-design will be needed to remove access barriers and ensure services are culturally and linguistically competent. As discussed in the recent BMJ special issue on racism in medicine, investment is also needed to improve medical education and increase unconscious bias and anti-racism training for medical staff.

While neither these problems nor solutions are new, there may be a real moment of opportunity to respond to the powerful activism of the Black Lives Matter movement, and to “build back fairer” in the wake of the pandemic.

The Health and Social Care system under strain: Rethinking integration policies in the post Covid-19 era

Marcello Morciano, Kath Checkland, Matt Sutton, Jonathan Stokes

Originally published 1 July 2020

In 2019, the NHS published plans (‘The NHS Long Term Plan’) promising to introduce inventive, ambitious ways to bring NHS and social care together across England, working with the private and voluntary sector, and users and carers. Needless to say, things have changed since 2019.

Nevertheless, the recent COVID-19 pandemic is showing us just how important it is to have joined-up health and care services, especially for caring for vulnerable people like the elderly in care homes. If anything, there has been a renewed urgency to roll out ‘integrated care’ initiatives.

However, there is also the risk of acting too rapidly without a clear direction. In fact, we do not know yet the best way of integrating services or what factors lead to successful integration. There is no detailed review of locally implemented integration policies to enable stakeholders to compare them and share learning on best practices. We need this to understand what works best and why, to identify areas for improvement and encourage good and sustainable practice nationally.

In a paper, published (Open Access) in the journal Health Policy, we have conducted the first independent national evaluation of the main ‘Vanguard’ integrated care prototypes trialled by NHS England from 2015-2018. This was a massive programme, costing about £389 million and covering a population of around 5 million people (around 9% of the population of England).

The declared aspiration of the Vanguard programme was the development of `locally driven’ prototypes, which, if successful, could be rapidly spread across England. We summarise our analysis and findings below, which provides some preliminary evidence that can help policymakers choose their integrated care direction in this turbulent time.

The NHS Vanguard integrated care models

Fifty local areas were selected across England to act as Vanguards. Some Vanguards focused upon improving the integration between primary, secondary, community and social care, with the aspiration to provide more integrated care in the community. These included 23 sites who developed “population-based” flexible models to be adapted to the needs of their whole local population (known to policymakers as either ‘MCPs’ or ‘PACS’) and others focused specifically on care home residents, mainly older people (six sites, referred to as ECHs).

There was little instruction or advice as to what should be trialled within each model, beyond the populations outlined above. They generally aimed to improve care, but the official main aspiration was to reduce hospital admissions.

What we found

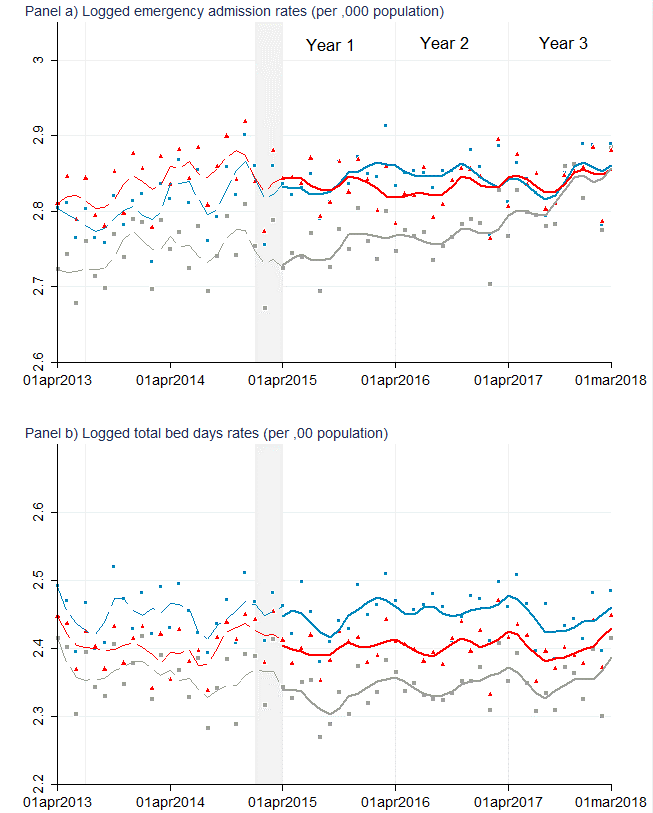

The easiest way is to visualise this. The figure below shows that there are parallel trends on the outcomes prior to the intervention being introduced (before the vertical grey line). In fact, non-Vanguard sites were doing consistently better on each measure (fewer emergency admissions and bed days), and there was an increasing trend of emergency admissions across the board.

What is also clear from below is that, in the post-intervention period, especially in the final year of the Vanguard programme, the Vanguard sites were resistant to a national trend of increasing emergency admissions. The sites that implemented integrated care aimed specifically at care homes did the best in this respect, starting with a worse rate of emergency admissions prior to the intervention and finishing better than the population-based Vanguards.

On the other hand, there was very little change in the bed days outcome, trends remain parallel throughout the post-intervention period.

Using a robust difference-in-difference statistical approach, we estimated that over the three-year period of the Vanguard programme, care home sites experienced an overall significant net reduction in emergency admissions of about 4.2% relative to the non-Vanguards. The net reduction in emergency admissions occurred mainly in the third year following implementation (-6.5%).

There was a reduction in emergency admission in sites involved in “population-based” models (MCP/PACS) too, but the effect was found to be statistically significant only in the third and final year of the programme (-3.1%).

We did not find any significant effect on total bed-days.

The take-away message

National and international experiences have shown that arranging an efficient integrated health and care system is not straightforward. The positive finding we have shown, is that integrated care has some potential to change desired outcomes, especially by targeting vulnerable groups in care homes that are a priority.

But, it is important to consider these were modest relative reductions in emergency admissions. Moreover, our results clearly show no net changes in the first year and relative reductions in emergency admissions only became significant after three years. This suggests that, even in a relatively straightforward organisational context such as care homes, where initiatives can be applied to whole resident population, achieving desired results takes time.

Finally, the modest net reduction in emergency admissions we have documented was achieved with the help of considerable additional funding and a dedicated support programme for Vanguard sites. It remains to be seen what can be achieved in a different environment. Three important lessons to be taken into account when re-shaping the system for the post-COVID-19 era.

The Environment

The environment has been a key topic of local, national and global politics over recent years as research develops and countries attempt to cut emissions and push towards net zero.

Lockdown highlighted the negative impact our pre-COVID lives had on the environment as evidence shows CO2 emissions decreased slightly due to stay at home restrictions. In contrast, it has also shone a light on the importance the population places on the environment, as we found respite in the outdoors to help improve our wellbeing and mental health.

This section features three blogs focusing on varying areas of the climate change and sustainability.

- Tackling the twin crisis of COVID-19 and climate change by Professor Alice Larkin (Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research). The article argues that decision-makers must take rapid action to invest and design policies that drive radical regional and national interventions to the climate crisis, that avoid disproportional impact resulting in further inequalities in certain groups and communities.

- Mobility transitions: COVID-19 and building back better post- carbon transport futures by Dr Cristina Temenos (Manchester Urban Institute). She states that policies developed must consider lowering our energy consumption by altering ‘norms’ and collective behaviours, leading to sustained but also realistic approaches in lowering consumption. Policies must not depend solely on technology changes or advancements but create short- and long-term plans that benefit different needs and routines.

- COVID-19 and sustainable everyday routines by Dr Claire Hoolohan. The article calls for the introduction of bold demand management practices on a micro and macro level that allow people to have differing schedules and routines which work best for them, their families, and their employers in order to reduce energy consumption.

- Rise to the top: Socially responsible public procurement by Sandra G. Hamilton (Manchester Institute of Innovation Research). She calls for OECD countries to adopt social value weighting in their public procurement strategy, and states that the revision of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) must be carried out, requiring the mandatory inclusion of social criteria.

Policy@Manchester, along with our leading experts, has explored how to mitigate the climate crisis while driving local prosperity, jobs, resilience and equality in a publication called On Net Zero.

Tackling the twin crises of COVID-19 and climate change

Alice Larkin

Originally published 16 November 2020

We’ve learnt two important lessons so far from the pandemic. The first is that our priorities can shift dramatically to tackle an emergency. The second is that change can take place quickly.

I’d like to share how these observations can be harnessed to tackle the climate emergency because, with everything going on in the world right now, you’d be forgiven for forgetting that we’re in one.

I’ve spent the last 18 years trying to understand the scale of the climate emergency and how our energy systems should transform to minimise carbon emissions. ‘Energy systems’ can sound rather technical but what I mean is how you and I use energy every day. What we use it for, when we use it, how much we use and where it comes from.

The climate emergency we’re facing is so great that mitigating the damage we are doing now, and the damage that will be done in future, requires much more than just increasing the amount of renewable electricity on our National Grid. We need to consider all the ways that we consume energy: from travelling to heating our homes, cooking to the industrial manufacture of goods; and critically, we need to do this quickly.

This is why it’s not just about technology. We know that a wide variety of technical solutions exist for cutting CO2 emissions, but some will take decades to be sufficiently widespread to make the difference that is actually needed in the next five or ten years. Coming from an physical sciences background and spending most of my career working with engineers and social scientists, I know that modelling theoretically how an idealised technology such as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage might cut CO2, is very different to the more complicated process of widescale and rapid infrastructure deployment. I’m thinking of things like the construction of new nuclear power stations; retrofitting alternative technologies for heating every single UK home; designing and deploying an extensive network of electric vehicles charging points; and perhaps most importantly in the current debate – the large scale roll-out of new CO2 removal technologies.

That’s why it matters how much energy we consume. If we can consume less, then we won’t need to transform as much high carbon infrastructure – but this is rarely the focus of CO2 mitigation discussions.

Consuming less energy has previously taken a back seat in the policy debates to decarbonising our energy supply. One of the reasons for this is that it requires changes to individual and collective behaviour, attitudes and expectations; aspects that are seemingly more politically sensitive than a shift in technology.

For example, I’ve worked for years on cutting the CO2 from air travel but the appetite for reducing flights, or even just curbing growth rates, has been minimal despite the widespread understanding that decarbonising aviation will take longer than the time we have to meet our Paris Climate Agreement objectives.

Yet consumption shifts can be implemented now. For example, research from The University of Manchester in June of this year analysed shipping emissions and the impact policy interventions could have when applied to existing vessels. Our research revealed that without making changes to energy consumption now, by adopting slower speeds or retrofitting ships with energy saving measures such as modern sails, the shipping sector will be unable to meet Paris targets, even assuming new vessels are able to run on zero-carbon fuels from 2030. Essentially, our research showed that it is vital to apply measures to decarbonise shipping within existing infrastructures to achieve milestone reductions while, simultaneously, developing new transformative technologies.

So, with just under twelve months until COP26 begins, what have we learnt from our response to COVID-19 to inform how we can respond to the climate change crisis? How can we equip our Government to deliver the UK’s defining action on climate change?

We’ve learnt that people can work and live differently. We can accept less commuting, less flying, less buying material goods; all energy consuming activities. We’ve accepted these changes because we know that there is a threat to human society.

We now need to apply that learning to our twin crises. Lockdown has shown that when leaders unite in recognition of a shared crisis, we adapt. This indicates that if the same leadership approach was taken to the climate emergency, we would accept changes that specifically reduce energy consumption, and supports the huge investment required in low-carbon infrastructure.

We’ve also learnt that we need more than a temporary change in our levels of energy consumption to combat climate change. Analysis of global emissions during the spring lockdowns reveals an average global reduction of 17%. However, this analysis also shows that even if some restrictions remain in place to the end of 2020, as they are likely to, the overall reduction will be much less. This indicates that while our lives were temporarily transformed, our reliance on fossil fuels remains. To ‘build back better’ we need structural and societal change that is sustained, far-reaching, and increased to meaningfully tackle the climate emergency.

To achieve this, we need significant investment. This brings me to a third matter we’ve learnt: we know that when the crisis is big enough, investment can be found. We now need investment to reflect the scale of the climate crisis. We need decision makers to direct investment, that we know can be made available, to drive rapid and radical regional and national interventions.

Clever investment now, at this crucial pivot point that has been brought about not only by COVID-19, but also the underlying attention on the climate emergency from the climate movement, could positively transform systems and society away from fossil fuels, whilst simultaneously improving employment, equality and human well-being. To support climate change goals we will need to retrofit our entire housing stock which in turn helps to address fuel poverty, re-purpose our roads for cycling and walking – improving our air quality, and accelerate our renewable energy roll-out. All these green projects create more jobs, while delivering short term returns for society that avoid long-term damage that will come at a high cost.

Now is the time to ‘green’ society and pursue a future that considers local prosperity, jobs, resilience and equality as we reassemble our daily lives.

Not only has COVID-19 given us lessons that we can learn from, but it has also created a flux in our everyday routines. We need decision makers to take advantage of this flux to develop policies that can lead to sustained but acceptable reductions in energy consumption – focusing on delivering change in the near term.

If we don’t take advantage of this moment in time where we have demonstrated that society can accept deep change, then we will pass up our opportunity of a lifetime to help future generations.

Mobility transitions: COVID-19 and building back better post- carbon transport futures

Cristina Temenos

Originally published 5 November 2020

The need to reduce carbon emissions in the transportation sector isn’t a new idea. Longstanding political debates surrounding efficiency, cost, and lifestyle change have long held that transition to low carbon technologies, planning for low carbon futures, and implementing meaningful change must happen slowly over time. But COVID-19 has shown us that the only barrier to efficient low-carbon transition is political will. For example, municipalities in Greater Manchester and other cities in the UK have rapidly innovated car-free streets and segregated cycle lanes. Yet there has been debate about whether these interventions should remain permanent. So, how do governments build back better for the long-term?

This is a question my research team and I have been examining since 2014. Our Living in the Mobility Transition project, led by Professor Tim Cresswell and Professor Peter Adey, looked at policies and government initiatives to transfer to low-carbon ways of moving across 14 countries: United Kingdom, Canada, Norway, The Netherlands, Portugal, Brazil, Chile, South Africa, United Arab Emirates, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Singapore, South Korea, and New Zealand. We found that while there is no ‘ideal low-carbon mobility transition policy’, there are policy practices that can help guide decision-makers in constructing effective policies. I introduce these practices below, and more details can be found in our policy brief.

Importance of social context

A mobility transition is not straightforwardly a transport technology transition. Focusing on the technologies with little regard for the social context is likely to result in full or partial failure. At a macro level, the most straightforward approach to reducing carbon emissions from transport is to: a) reduce or eliminate the need to travel and b) decrease the length of necessary trips. An approach to mobility transitions informed by work on the social context and meaning of mobility and sensitive to local and national context is most likely to include as many stakeholders as possible and have a greater chance of success.

It is important to consider who policies work for. While it is possible to say that carbon tax policies, for instance, are likely to result in reduced carbon emissions, it is also clear that without redistribution, such a policy is socially regressive and likely to disproportionately impact impoverished, marginalised and, particularly, rural communities. Similarly, the promotion of a Bus Rapid Transit system may well reduce carbon emissions in the city but is far from ideal if it is inaccessible to the mobility disabled. More than that, by being inaccessible it actually contributes to the production of disability. One way to think through this issue is to produce transition policies in bundles. A carbon tax, for instance, could be coupled with redistribution policies that actively assist the impoverished and marginalised populations who disproportionately bear the brunt of the costs.

While the absolute reduction in carbon emissions is one important measure, it is necessary to consider other possible impacts such as the social ones noted above. The widespread adoption of automated electric vehicles, for instance, could result in unsustainable increases on power production. Similarly, the sudden possibility of cars with no inhabitants could increase congestion in an alarming way as cars will be travelling with no driver or passengers.

Strategic alignment and complexities

Policymakers need to consider the strategic alignment of transition policies at different scales. They should ask in what ways will transition policy be more or less likely to fail given their nesting within often contradictory scales and times of policymaking? The most significant mismatch of policy at different scales and times of policymaking occurred when medium- to long-term environmental transition concerns were in contradiction to shorter-term economic goals of growth and profitability.

It is also important to avoid overly simplistic, reductive or universalist understandings of mobile people. Transport planning has traditionally assumed a universal human being as the typical mobile subject. Commuters have been imagined as though they have no gender, passengers have been entered into flow models as seemingly universal subjects, and issues of disability and accessibility have not been included in consideration of transition. In reality, any effective transition policy must account for the diversity of human bodies and subjects and their different needs.

Separating mobility and economic growth

There is a danger of top-down policies influenced primarily by the private sector telling citizens how to move based on market logics. Even the language used can alienate potential allies by creating meanings for mobility that are not aligned with the needs and desires of everyday life. Policymakers need to become policy-enablers who encourage and stimulate local organisations, coalitions and individuals in community participation for mobility transition. Rather than being aligned with the dominant narrative of economic growth, mobility needs to become aligned with notions of citizenship and common good.

Of all the tensions that lead to transition failure that we have identified, this is the most frequent. As long as mobility and economic growth are conceptually and culturally linked then transition policies can never reach their full potential. Low-carbon mobility transitions are often added on as afterthoughts to economic purposes. There are linked-up solutions that start from a position of the public good that complement our findings. The New Green Deal, which is focused on finding just transitions that work for people and society, and New Municipalism, which has seen success in places as diverse as Barcelona in Spain to Preston in the UK, are two such examples. Policy practices such as those we present in our brief are important frameworks for thinking about ways we can build back better post-carbon futures.

COVID-19 and sustainable everyday routines

Claire Hoolohan

Originally published 1 October 2020

When a practice becomes ‘locked-in’, it means that people’s capacity to act in different ways is limited, despite perhaps understanding the implications of their actions and even hen supportive of change. Often, the cultural and material conditions in which routines are situated are satisfactory, which leads to little critical reflection. The more people that participate in unsustainable practices, and the more regularly they do so, the stronger the lock-in effect becomes.

In contrast, COVID-19 has caused unprecedented disruption to everyday life, prompting a period of forced experimentation as people in all kinds of different situations adjust to new ways of living. The changes have been extensive, rapid, and unexpected – affecting the way we work, socialise, care for others, exercise and entertain ourselves.

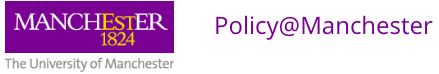

Research from The University of Manchester, as part of the ESRC Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformation, explores the impact of COVID-19 on the UK public’s lifestyles and routines, focusing on activities that have significant impacts on climate change (eg, travel, food, product consumption, and energy use). Unsurprisingly, the results show that people’s everyday routines have changed in many ways during this time, and some of these changes are to the benefit of sustainable consumption.

For example, we asked people about how their shopping, cooking and eating routines had changed. Respondents described how restrictions have led to more time at home and less spontaneity in cooking and eating. As a result, people are better able to keep track of what is in the fridge and what needs using, resulting in 35% of respondents reporting less food waste and an increase in waste-reducing practices like batch-cooking, freezing and preserving food.

There are also references to the idea that in a world with coronavirus, food waste equates to risk, as it means more journeys to the supermarket where people are concerned about transmission.

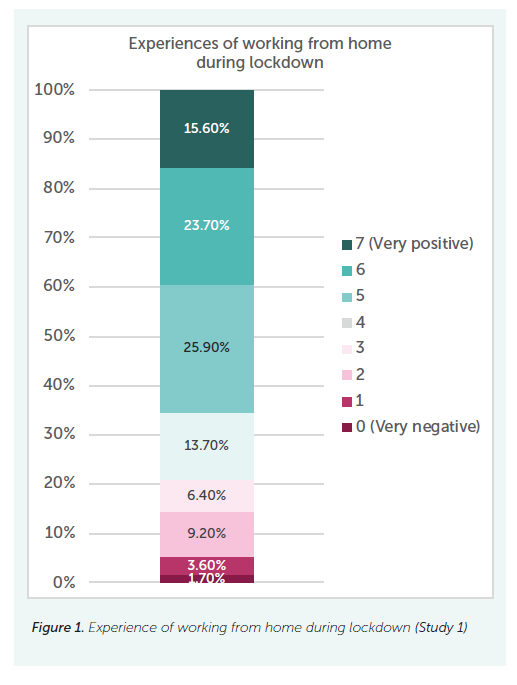

These findings signal the importance of systemic factors such as timetabling and scheduling, and wider trends that have become engrained throughout the 20th Century, like commuting. Several respondents described how their shopping habits had changed because they no longer travelled to and from work:

“Previously we would do small quick shopping trips every 1 or 2 days, to pick small stuff up at lunchtime or on the way home from work. We can’t do this anymore as we’re not in the office, so we’ve been doing one big shop and buying more to reduce the number of trips. We plan really carefully now so that we don’t waste anything, because going to the shop risks our health and the health of others.”

Here we see how shopping, meal planning and food waste become entangled in working and commuting, and how pre-COVID habits become unsettled as lockdown disrupted daily routines. These sorts of findings are interesting if we reflect on other emissions hotspots, like rush-hour and peak energy demand. Shifting the timing of energy demand provides a range of benefits, from reducing local air pollution to balancing the grid and enabling more widespread use of more intermittent forms of renewable energy.

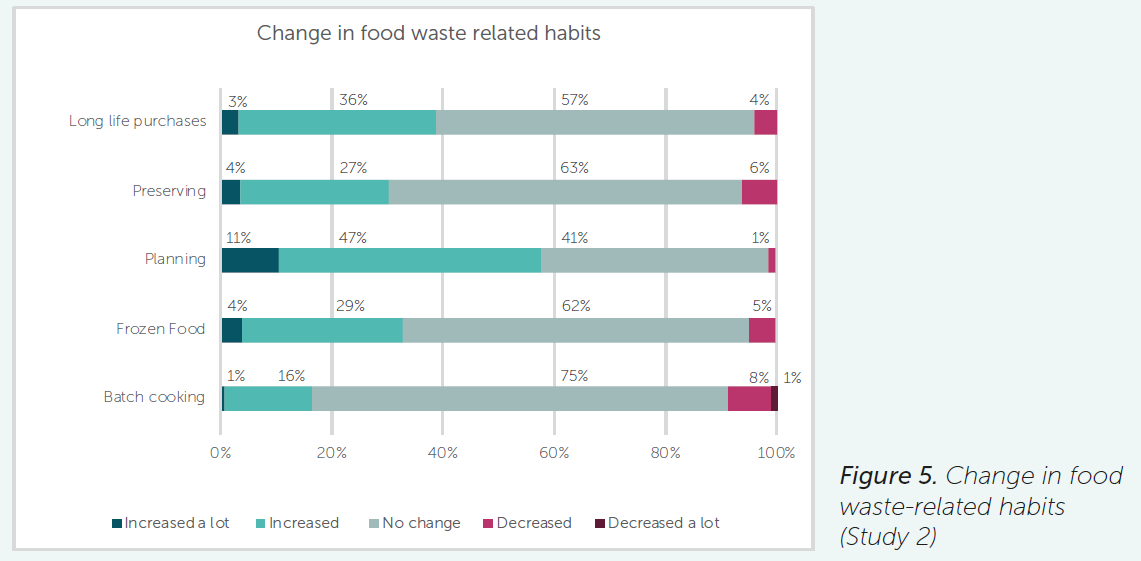

Many of the common approaches taken to ‘time-shift’ routines focus on individual action – time-of-use tariffs and smart displays to encourage people to use energy ‘off-peak’. Yet few strategies are being rolled out to alter the broader time-space of daily routines. COVID-19 has given us a window to observe what happens when ordinary schedules – 9-5 work day, the school run, weekdays/weekends – are suspended. Working from home and having children out of school has done away with many of the more formal structures that people typically experience. And as a result, many respondents in this survey talk about how they’ve begun to experimenting with different ways of structuring their time.

For flexible workers who previously stuck to a 9-5 working day, the shift to working from home, often combined with a need to care for children, has led to great variety in how people are flexing their usual commitments – some taking longer days with breaks, or working earlier or later. There are also plenty of people describing how they switch between shorter, more concentrated ’shifts’ of work and childcare, alternating with their partner.

“As before, I usually work a 7-8 hour day, but now I usually take breaks amounting to 2-3 hours during the day, to do other activities, so I start earlier and work into the evening. I’ve found this more do-able than sitting for a 7-8 hour continuous stretch.”

This seemingly mundane resequencing of daily activities, if continued, could deliver the time-shift needed to redistribute peak energy demand. An important question then, is how, as a society, we can recover from coronavirus in a way that continues to allow space for the low-carbon habits that this survey has observed.

One line of enquiry is to reimagine employment, and potentially schooling, to benefit demand management and perhaps also wellbeing, given that people seem to appreciate having greater control over their time. For some years people have discussed the possibility that shorter working days and weeks might have benefits for sustainability and wellbeing. However, it has been difficult to gather the evidence of the impacts of such a change at a large scale and across different industries/communities. COVID-19 has forced that experimentation, and what we see in the results is that there does indeed appear to be evidence that supports the case for experimenting with different temporal rhythms.

However, it is important to recognise that for some people this time has been deeply difficult. People are concerned about their loss of productivity, they’re worried that they’re not able to do their best for dependents whilst also juggling work, and many have first-hand experience of coronavirus itself. If policy is to support experimentation with working hours, this needs to be done in an empathetic way that recognises different people’s situations and needs, and works to ensure this is an experience that does not benefit/disadvantage certain groups more than others.

Bold demand management measures are needed if the rapid and extensive reductions needed to limit the negative impacts of climate change are to be achieved. COVID-19 has forced extensive experimentation as people adapt everyday routines to new circumstances, and the early results from this research illustrate major implications of this experimentation for the ways in which resources such as water and energy are used, and how people eat and travel. Coronavirus has therefore created an important set of conditions within which to understand discontinuity in everyday practice at a large scale.