Healthy Hearts

Improving cardiovascular health nationally and globally

Contents

Foreword

Dr Charmaine Griffiths, Chief Executive, British Heart Foundation

Change for the better: how can the NHS Health Check better help patients manage cardiovascular disease risk?

Sophie Griffiths, Dr Brian McMillan, Dr Kiera Bartlett, and Professor David French

Beyond survival: addressing cardiovascular disease in endometrial cancer survivors

Dr Heather Agnew, Dr Sarah Kitson, and Professor Emma Crosbie

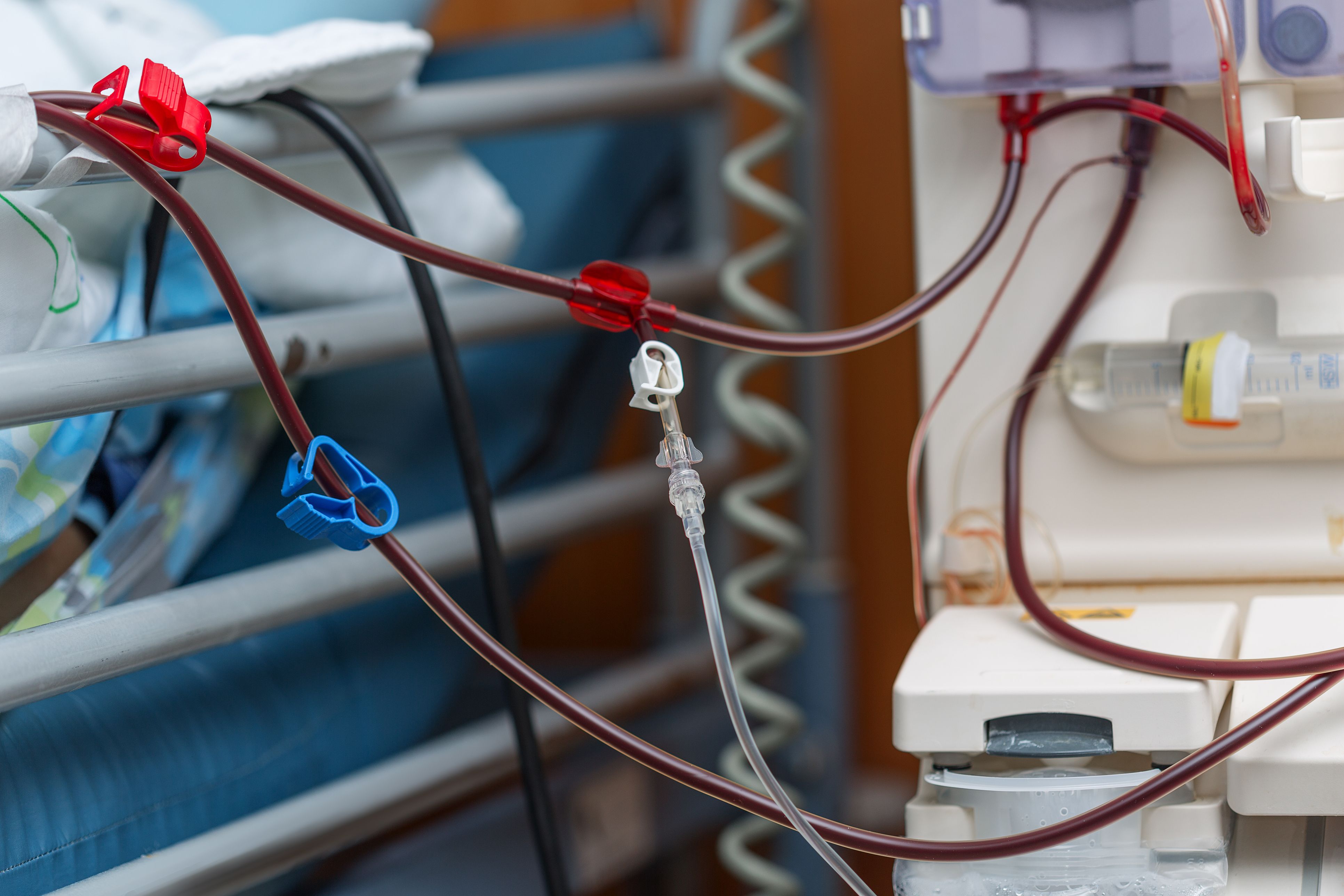

Shifting the silos: transforming care for cardiorenal metabolic disease

Dr Saif Al-Chalabi, Professor Smeeta Sinha, and Professor Philip Kalra

Clearing the air: pollution and cardiovascular health

Professor Holly Shiels

Cardiovascular disease threatens to leave behind lower and middle income countries

Dr Gindo Tampubolon, Professor Delvac Oceandy, and Dr Asri Maharani

Foreword

Dr Charmaine Griffiths, Chief Executive, British Heart Foundation

Every three minutes in the UK, someone dies from cardiovascular disease (CVD). It remains one of the UK's biggest killers, tearing families apart and causing untold heartbreak to far too many. In the last half a century, huge strides have been made to halve the number of people dying from heart and circulatory diseases in the UK each year. But worryingly, this progress is now at risk.

We are in the grip of a heart care crisis, with more people dying prematurely from CVD than at any time in the last decade, and near-record numbers of people on cardiac waiting lists across the UK. Every year, CVD healthcare costs are an estimated £12 billion in the UK, and heart disease is the single largest factor behind people leaving the workforce early due to ill health. It also contributes to around one-fifth of the life expectancy gap between the most and least deprived fifth of the population.

But hope is not lost; British Heart Foundation (BHF) analysis suggests that with the right action, up to 11,000 early deaths a year from heart and circulatory diseases could be avoided by 2035 in England.

Much of the CVD burden is preventable so we must get serious about tackling the biggest causes of heart attacks and strokes. We know that factors such as tobacco, our unhealthy food environment, and, as detailed by authors in this collection, air pollution, are persistent obstacles to a healthier population. Similarly, more can be done to diagnose and manage conditions such as high blood pressure, which is linked to half of all heart attacks and strokes in the UK.

At the same time, there must be a focus on getting patients the right care at the right time. Too many people are waiting too long for potentially life-saving treatments. The upcoming Ten Year Health Plan is a vital opportunity to get our health care back on track and ensure that patients have the joined-up, personalised care they need. But beyond this, it’s an opportunity to set out how our health system can harness the fast-paced growth in data science, artificial intelligence and innovation that could deliver transformational change for patients.

Lifesaving cardiovascular research is at the heart of the BHF, and the publication of Healthy Hearts is a timely reminder of the critical role research breakthroughs play in sparking the changes in national policy and practice we need to see.

The policy recommendations put forward in this world-leading collection outline concrete steps policymakers must consider as they seek to address the UK’s biggest killers and create an NHS fit for the future. Reversing a decade of lost progress in tackling CVD is within our reach.

It is my great privilege to introduce Healthy Hearts from Policy@Manchester, a truly impressive collection of innovative research and sensible policy recommendations on the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. The Government has made a clear commitment to tackle the UK’s biggest health challenges, including CVD – and they are right to do so. I hope that in reading this collection you, like me, feel a sense of excitement about what is possible, and that policymakers and healthcare leaders feel inspired to take much-needed steps that will get us ever closer to another half century of unstoppable progress.

Change for the better: how can the NHS Health Check better help patients manage cardiovascular disease risk?

By Sophie Griffiths, Dr Brian McMillan, Dr Kiera Bartlett, and Professor David French

The NHS Health Check reaches more than a million patients each year. It involves cardiovascular risk assessments, which can be used to develop management strategies to help patients lower their risk of cardiovascular disease. But how often do these checks lead to sustained behaviour change? Here, Sophie Griffiths, Dr Brian McMillan, Dr Kiera Bartlett, and Professor David French discuss how new technologies and communication techniques can enhance the effectiveness of the Health Check in improving patients’ cardiovascular outcomes.

- To more effectively incentivise change in patients’ behaviour, the Health Check should focus on providing actionable, personalised advice.

- A digital component of the Health Check may have a role to play in this, allowing patients to access more bespoke information at their own pace.

- The Diabetes Prevention Programme also offers a strong model for how the Health Check can act as a cost-effective ‘front door’ to further support.

In the 2022-2023 period, 1.1 million Health Checks were delivered by the NHS and local authorities to patients aged 40 – 74, who are eligible for a check every five years. These checks involve a cardiovascular risk assessment, alongside risk communication and management strategies for patients. However, these checks do not consistently lead to behaviour change, with patients expressing a need for more tailored, ongoing support to maintain their motivation and adopt long-term changes. Health Checks also often fail to reach the people who may benefit most, who are typically people from marginalised communities.

In the first instance, there is a challenge in determining how many patients act on the advice given during their Health Check. In one study, around 70% of attendees (45 out of 66) who responded to a survey after having received a Health Check reported that they made at least one lifestyle change. However, this figure is likely inflated, and qualitative evidence has found patients face numerous obstacles when attempting to change their behaviour.

One issue is that the funding and monitoring arrangements of the NHS Health Check programme currently focus on the number of checks conducted, resulting in an overemphasis on the volume of checks delivered – but potentially at the expense of the quality of the checks in supporting health behaviour change.

Most health check attendees do not receive any treatment or referral after a check, and statin prescribing in particular is much lower than guidelines recommend. Evidence on behaviour change and improvements in CVD post-check is sparse – but the data that is available indicates the rate at which advice, information and referrals are given varies widely for different risk factors, and appears to fall well below the recommended thresholds for intervention.

Towards more effective risk communication

Research at The University of Manchester has shown that risk communication alone is often ineffective for behaviour change. The main barrier to change is frequently that people lack skills to self-regulate their behaviour, i.e. put their good intentions into action, rather than low motivation. Therefore, a more effective approach to risk communication may be to use it to encourage individuals to join behaviour change programmes, where they can receive structured support to develop essential self-regulatory skills, such as goal setting and self-monitoring.

Changing self-efficacy (the belief in one’s ability to change or perform a behaviour) and helping people understand how behaviour changes will reduce disease risk will make risk communication more effective in driving behaviour change. This can be achieved by providing patients with explicit information on how altering their behaviour can reduce their risk, alongside specific strategies to build self-efficacy. Research at The University of Manchester is exploring how these approaches could be integrated into a digital NHS Health Check to support behaviour change.

It may also be helpful if they are accompanied by other behaviour change techniques, such as adjustments to the social or legislative environment, or those that target self-regulatory processes—like goal setting and planning.

Patients often leave Health Checks feeling reassured, even when risk levels require action. Effective communication should focus on modifiable risk factors rather than current risk scores, encouraging a proactive approach to health. Personalised advice and comparative risk measures, like "heart age," may motivate preventative actions better than general risk scores. Changes to NICE guidance now recommend lifetime risk assessments to engage those with lower short-term risk scores.

Moving beyond risk communication

Simply explaining cardiovascular risk may not be enough to prompt significant lifestyle changes. NHS Health Checks might benefit from integrating evidence-based psychological strategies, such as enhancing self-efficacy and self-regulation skills. Referrals to structured behaviour change programmes could complement Health Checks for better outcomes.

The NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme (DPP) offers insights into how a CVD prevention programme could operate, due to the similarities in risk factors and management. The NHS-DPP offers patients the option to participate either in group sessions or via digital platforms, helping them to understand the repercussions of type 2 diabetes and make changes to reduce their risk of developing the disease in the future. The programme includes behaviour change strategies that help individuals develop skills to support self-regulation of health behaviours. Research at The University of Manchester found that patients referred to the NHS-DPP had a lower incidence of type 2 diabetes compared to individuals at practices where the programme had not been deployed. It concluded that the introduction of the NHS-DPP reduced population incidence of type 2 diabetes in England for over 20,000 people in those practices that put the DPP in place, and is cost-effective, with a recent analysis showing projected savings close to £72 million over 35 years. Following this model, the NHS Health Check could be used as a referral into a similar prevention programme for CVD.

Digital health checks

The Department for Health and Social Care has announced a digital version of the Health Check. Three local authorities have been selected to pilot the new Health Check, with the aim of scaling it up to one million checks in the first 4 years. While the digital version is intended to complement, rather than replace, the face-to-face health check, policymakers must implement it carefully to avoid widening health inequalities, particularly among individuals with limited digital access or skills—the so-called 'digital divide'. Delivering Health Checks in community-based settings may be more effective at reaching underserved groups than those offered through GPs, highlighting the role of commissioning decisions in achieving equitable access.

As discussed previously, there is scope for a digital version of the Health Check in providing tailored support for patients. Research at Manchester has shown patients are keen on being signposted to services through a digital component of the face-to-face health check. This approach would allow patients more time to explore their risk information at their own pace and access tailored resources to support behaviour change, creating a more flexible and user-centred pathway to improve health outcomes. Patients have previously expressed dissatisfaction with the generic advice offered through Health Checks, so a more personalised approach delivered via digital platforms could be one way to improve this.

A Health Check for the 21st Century

The majority of cardiovascular disease cases in the UK are preventable, but despite this, CVD costs the NHS £7.4 billion every year. The Health Check offers a reliable, recurring opportunity to identify CVD risks and engage individuals in making healthier changes, and policymakers should ensure every advantage is taken to reduce the danger to these individuals. This means changing how patients are engaged with during and after the check, including more personally-tailored individual support through digital channels, as well as using it as a stepping-stone to other services.

Beyond survival: addressing cardiovascular disease in endometrial cancer survivors

By Dr Heather Agnew, Dr Sarah Kitson, and Professor Emma Crosbie

Nearly 10,000 cases of endometrial cancer are diagnosed in the UK each year. But for patients who survive their cancer, cardiovascular disease poses an additional and ongoing risk, accounting for a quarter of all deaths in endometrial cancer survivors. Here, Dr Heather Agnew, Dr Sarah Kitson, and Professor Emma Crosbie explain how a more targeted approach to tackling cardiovascular disease in cancer survivors could improve health outcomes, including for women from the most deprived socio-economic groups.

- Nearly 90% of endometrial cancer survivors have at least one undiagnosed or undertreated cardiovascular risk factor, with several factors common to both cancer and cardiovascular disease.

- A cancer diagnosis presents a ‘teachable moment’, where patients can be provided with personalised advice and support.

- To ensure support is maintained, a joined-up approach to CVD screening in endometrial cancer survivors is needed between primary and secondary care services.

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women in high income countries, with nearly 10,000 cases diagnosed every year in the UK alone. The incidence of the disease has doubled in the last 20 years, with this trajectory expected to continue. Despite relatively good survival outcomes compared to other cancers, individuals with a history of endometrial cancer have a higher risk of death than those without. Within this group, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a significant risk.

Previous research from The University of Manchester found endometrial cancer survivors have a higher prevalence of undiagnosed and untreated cardiovascular risk factors than the general population, including high blood pressure and high cholesterol. This is perhaps to be expected, given that endometrial cancer and CVD share the common risk factors of obesity and diabetes. Indeed, women with diabetes have twice the risk of endometrial cancer compared to non-diabetic women, even after controlling for the effects of body weight, suggesting a close relationship between the two conditions.

However, despite the known association, screening and interventions for cardiovascular risk factors are not routinely undertaken in endometrial cancer survivors, meaning the true prevalence of CVD risk factors in this group is likely higher than previous estimates suggest. The findings of research led by the Manchester group support this, with screening of a cohort of endometrial cancer survivors finding 57% had previously undiagnosed diabetes or hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar), compared to just 11.5% of a control group. Within the same group, 89% of cancer survivors had undiagnosed or undertreated CVD risk factors, compared to 54% of controls. 22% of the survivors had three or more CVD risk factors.

Now, new findings show that 5+ years post-diagnosis, CVD is one of the leading causes of death for endometrial cancer survivors, accounting for 1 in 4 deaths.

Utilising the teachable moment of a cancer diagnosis, researchers at Manchester have conducted a study to assess cardiovascular risk in individuals with a history of endometrial cancer, and then provide these individuals with tailored advice on reducing their risk. 80 individuals with a history of endometrial cancer participated in the study, of whom 18% were of Asian or Black ethnicity, and 34% were from the most deprived socio-economic backgrounds.

All of the participants had at least one potentially modifiable CVD risk factor, with an average of four. After this risk assessment, each participant was then given tailored lifestyle advice and NICE recommended pharmacotherapy, alongside their routine cancer follow-up. At 12 months, 45% had successfully instigated some or all of the recommended changes, with 23% successfully implementing half or more of the changes recommended to them to target their cardiovascular health.

While a positive step, it was important to understand why over three quarters of participants were unable to implement more than half of the recommended changes. Through interviews, they identified barriers and facilitators to implementing lifestyle changes. The challenges they faced included pre-existing health conditions, family, age, lack of knowledge, money, time, fixed mindset, and poor relationships with healthcare providers. The cost of healthy food and gym memberships were particular barriers for those from more deprived socio-economic groups.

Another common theme was the lack of individualised support, with generic information not appropriate for participants with underlying health problems, or non-Western dietary preferences.

Of the facilitating factors, perceived benefits to overall health and family were strong motivators for change, alongside a desire for independence in daily living and the impact of seeing results. Clear advice and information which promoted knowledge and awareness, alongside a good patient-healthcare provider relationship, were important facilitators of change.

Policy recommendations

Health policy must reflect that endometrial cancer survivors are at high risk of cardiovascular disease. There is a window of opportunity when these individuals are undergoing follow-up in which their cardiovascular risk factors can be targeted and treated, to potentially reduce preventable deaths. Barriers to making these changes reveal inequalities in survivorship care, and these changes must be addressed with consideration of diverse backgrounds, physical capabilities and socioeconomic context.

As such, routine screening for CVD in individuals with a history of endometrial cancer should be a shared responsibility of both primary and secondary care. Introduction of this screening, and subsequent interventions for cardiovascular risk factors in women following treatment for endometrial cancer, would be more effective than a similar programme aimed at the general population.

For those where risk factors are identified, individualised support to make lifestyle changes should be offered, including dietary and physiotherapy input, plus education on cardiovascular health in this context for both patients and healthcare providers. There is a role for social prescribing link workers in connecting at-risk patients to community-based support, as well as health and wellbeing coaches in setting and maintaining behaviour change goals.

Being diagnosed with cancer is a highly emotional experience, which inevitably leads to questions about risk and prevention. Treating this as a teachable moment presents an opportunity for discussions about cardiovascular risk; arguably, this is more important than the efforts made in routine follow-up to identify recurrent disease in women who have generally been cured of their endometrial cancer. Weight loss is an obvious intervention to reduce the risk of both CVD and cancer, but one that is difficult to sustain by dietary restriction and lifestyle change. Instead, health policymakers should adopt a strategy of identifying and improving undiagnosed or undertreated cardiovascular risk factors, with appropriate drug therapy one reasonable alternative.

The Health Mission adopted by the government includes goals to prioritise women’s health, as well as moving to a more preventative model of healthcare. A cardiovascular screening programme in endometrial cancer survivors captures both of these objectives. The evidence on the risk of cardiovascular disease to these patients is clear: now is the time to act on it.

Shifting the silos: transforming care for cardiorenal metabolic disease

By Dr Saif Al-Chalabi, Professor Smeeta Sinha, and Professor Philip Kalra

There are strong links between renal and cardiovascular disease, with chronic kidney disease contributing to around 12,000 excess heart attacks each year in England alone. However, siloed models of care may fail to deliver adequate care due to potential complex interactions between multiple disease management and the lack of continuity of care. Here, Dr Saif Al-Chalabi, Professor Smeeta Sinha, and Professor Philip Kalra outline a new, patient-centred model of healthcare to improve outcomes across cardiorenal disease, adopted across the Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust.

- The speciality-specific model of care in the UK creates a fragmented approach to treatment for people with multimorbidity, leading to recurrent hospital visits and admissions.

- Optimising care for people with cardiorenal metabolic diseases requires a patient-centred care led by interdisciplinary healthcare teams and supported by shared care protocols, telemedicine, and new funding models.

- Establishing a holistic healthcare approach would build on previous shifts towards integrated care, as well as current health policy strategies to move to a more digital, community-focused care model.

Cardiorenal metabolic diseases—including heart failure, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes, and obesity—share overlapping pathophysiological pathways and risk factors. These conditions impose significant burdens on healthcare systems, and negatively impact clinical outcomes. Worldwide, CKD alone is responsible for approximately 1.4 million annual cardiovascular deaths, and over 25 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs, equivalent to the loss of one year of healthy life).

In England, CKD is estimated to affect more than 7 million patients, of whom nearly half are living with later stage CKD (stages 3 – 5, marked by progressive loss of kidney function). This costs the NHS around £6.4 billion pounds in direct costs, while CKD also contributes to poor cardiovascular outcomes. Between 2009 – 2010, CKD contributed to more than 7,000 excess strokes and 12,000 excess myocardial infarctions (heart attacks), and for every 100 patients with later stage CKD, 6 will experience cardiovascular health events.

As with many conditions, health inequalities play a role. Research led by The University of Manchester showed an association between CKD and deprivation, with unemployment, lower educational attainment, and lower household income all associated with poorer health outcomes.

Given the links between renal and cardiovascular disease, it is clear that a holistic, patient-centred approach is needed to care. However, traditional, siloed specialty-specific models of care often fail to address the complexities of these interrelated conditions. This fragmented approach leads to inconvenience for patients, who face a greater number of healthcare appointments and interactions, and limits continuity of care. The result is complicated management, variable and inconsistent treatment, and diminished patient engagement.

The need for a patient-centred approach

Optimising health for individuals with cardiorenal metabolic diseases requires a patient-centred approach led by an interdisciplinary care team with appropriate competencies. This approach should leverage shared care protocols, integrated care across primary and secondary care as well as harnessing innovation. This may include utilising technology to support remote monitoring and delivery of care closer to home. To support these efforts, stakeholders and policymakers must adopt innovative policy models by allocating targeted funding and implementing frameworks that promote investment in prevention of long-term conditions, integrated and comprehensive care as well as ensuring healthcare providers are well-equipped to deliver care for people living with multiple long-term conditions.

Moving away from traditional frameworks to adopt a strategic organisational approach that focuses on patients rather than a single disease or organ is essential. This shift allows funding to flow from individual services towards services with shared goals. Funding can be used to develop interdisciplinary teams, digitally enabled healthcare services, and patient self-management programmes. One way to divert more funding to these care models is to fundamentally change the predetermined set of outcomes, from disease-specific to patient-centred outcomes. This can be achieved by creating incentive structures for healthcare providers that reward the delivery of high-quality, coordinated care, including performance-based reimbursements that consider patient outcomes, satisfaction, and improvement in healthcare utilisation such as reductions in hospital readmissions. Reform of funding mechanisms to enable multi-year spending offer prevention focused offer may also enable systems to invest in prevention endeavours.

Reforms are needed to equip healthcare professionals with the necessary skills to care for patients with this cluster of interrelated conditions. General medical training includes cardiology, nephrology and endocrinology; however, services are largely confined to single specialties. The re-design of service models will enable medical teams to review patients across cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic conditions, rather than within the confines of an individual specialty.

This redesign applies to other healthcare professionals, who may benefit from the development of cardiorenal metabolic (CKM) competencies through modular training pathways. For instance, heart failure nurses may be able to develop competencies in CKD and diabetes recognition and optimisation.

Digital and physical infrastructure needs

Enhancing clinical services for cardiorenal metabolic diseases requires significant improvements in digital and physical infrastructure. Examples include systems that link electronic patient records between primary and secondary care, electronic alert systems to identify early changes in important cardiovascular parameters, and wearable technology for remote monitoring of cardiovascular parameters such as blood pressure. The main barrier to developing these services is cost, which can be addressed by evaluating the value of these services in preventing cardiovascular and renal events, thereby reducing medical care costs and sickness-related work absences.

Benefits of comprehensive services

Establishing comprehensive services for cardiorenal metabolic diseases can improve the uptake of cardio-renal protective therapies, optimise metabolic management, enhance clinical outcomes and quality of life, and allow rapid translation of advances in cardiorenal metabolic diseases into clinical practice. A cardiorenal metabolic service localises care through primary-secondary care coordination, enabling personalised and less fragmented treatment. It empowers patients with digital tools to manage their health and prevents prolonged illness by addressing cardiorenal metabolic risks early, reducing complications like cardiovascular events.

Aligning with government health strategies

This approach aligns with current health policy’s three strategic shifts in care delivery: hospital to the community, analogue to digital, and sickness to prevention.

The priority of moving from analogue to digital includes elements such as shared electronic patient health records, digital infrastructure, and data safeguarding. The University of Manchester is already leading work in this area, and an integrated cardiorenal care service would build on this learning. In particular, a shift to telehealth has the potential to address the disparity in health outcomes identified in more deprived areas, by improving access to healthcare service via remote technologies.

Community care, including the expansion of Community Diagnostic Centres and the shift to a ‘Neighbourhood Health Service’ approach for the NHS, play crucial roles in moving cardiorenal care to a more community-based, preventative focus. Identifying high-risk individuals in the community allows for early intervention to correct their disease trajectory, reducing morbidity and disability. For example, early identification of identification of increased levels of albuminuria (an early sign of kidney disease) in a patient with diabetes and starting appropriate medications can significantly halt CKD progression and reduce cardiovascular events.

Conclusion

Transforming care for cardiorenal metabolic diseases from siloed to comprehensive, patient-centred approaches is essential for improving clinical outcomes and reducing healthcare burdens. By adopting strategic funding, educational reforms, and enhancing digital and physical infrastructure, we can create a more integrated and effective healthcare system that benefits patients, healthcare providers, and the NHS as a whole.

Clearing the air: pollution and cardiovascular health

By Professor Holly Shiels

Air pollution is increasingly recognised as a major contributor to ill health, including cardiovascular disease. One of the most harmful chemicals released by burning fossil fuels – phenanthrene – is linked to heart disease, as well as other illnesses. Here, Professor Holly Shiels outlines work to investigate the sources of air pollution, the effect on cardiovascular health, and how policymakers can act to clean up our air to save our health.

- Of the 12 characteristics of cardiotoxicity, phenanthrene causes 11 of them.

- Burning fossil fuels – including in car engines, and wood burning stoves – is a major source of phenanthrene, with people in urban areas most at risk.

- Building on momentum from recent years, policymakers and public health officials should go regulate emission sources in new buildings, and introduce routine monitoring of phenanthrene and other pollutants.

Globally, poor air quality contributes to more than 4 million premature deaths each year, and is considered one of the biggest issues in global and public health for the next century. Numerous studies have established a strong link between air pollution and cardiovascular disease (CVD), as well as mortality. Exposure to particulate matter (PM) is associated with serious health issues such as cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, strokes, and heart attacks, with air pollution contributing to nearly 1 in 5 CVD deaths.

One of the harmful components released by burning fossil fuels is polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), including phenanthrene, a simple structure of three benzene rings. It is often carried on the surface of particulate matter, including very fine particulate matter (PM2.5), so measurements of particulate matter are frequently used as a proxy for phenanthrene exposure. This compound is present in food, water, the gas phase of air pollution, and on the surface of PM2.5. After being released by the combustion of fossil fuels, phenanthrene can break down into even more harmful products, either while still in the environment, or after entering the body.

The relative toxicity of particulates increases as they get smaller, with PM2.5 capable of reaching the smallest areas in the lungs and even entering the blood stream and translocating throughout the body. Humans can breathe in or ingest phenanthrene, and emerging evidence suggests it causes inflammation and oxidative stress which is linked to a range of conditions like gut and bowel diseases.

The impact of air pollution on cardiovascular health

Ongoing studies indicate that chronic exposure to phenanthrene and PAH causes remodelling of heart function, making the heart more susceptible to arrhythmia. This evidence is supported by studies using mouse and sheep models, as well as human tissue cell models.

An evidence review by researchers at The University of Manchester has linked PAHs exposure to higher levels of poor cardiovascular health in urban environments. These substances are cardiotoxic, meaning they disrupt the activity of the heart. Further research from The University of Manchester found that, of the 12 key characteristics of cardiotoxicity, phenanthrene induces 11. Other chemicals that have a similarly damaging effect on the cardiovascular system, such as lead or arsenic, are heavily regulated and monitored, and yet there is no international regulation specific for PAHs like phenanthrene.

People with pre-existing cardiac dysfunction, including those living with obesity, are more affected by air pollution. Older individuals are also more susceptible, potentially due to a stronger inflammatory response – similar to that seen in COVID-19 patients. As such, air pollution plays a role in exacerbating existing health inequalities.

To mitigate these risks, air filters can be effective as phenanthrene tends to stick to them, helping to remove it from the air. Different types of fuels produce different signatures during the refinery process, and the structure of phenanthrene and other PAHs can be modified by methylation, which can make them either less or more toxic.

Policy recommendations

To address the issue of air pollution as a driver of poor cardiovascular health, there are several concrete steps public health policymakers can take.

First and foremost, the Environmental Agency and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) should introduce routine monitoring of phenanthrene and other PAHs, which is not currently undertaken. Instead, PM2.5 is used as a proxy measure, but specific monitoring of PAHs will provide a better understanding of how these compounds travel from emission sources. Identifying hotspots of PAHs will allow for risk-appropriate mitigation strategies, as well as a deeper insight into the relationship between air quality and cardiovascular risk. Researchers at The University of Manchester have used commercially available equipment to develop new, cost-effective methods to measure these substances using columns linked to air pumps.

The Environment Act 2021 set a legal duty for the UK Government to reduce air pollution, including PM2.5, following widespread concerns about the impact of poor air quality on health. Once routine measurement of phenanthrene and other PAHs is established, Defra should update this legislation to include similar targets for reducing these compounds as well.

Secondly, it is advised to introduce air filters in places where vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and those with pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors, are located. Priority should be given to areas near sources of emissions, such as care homes and hospitals near busy roads.

Lastly, wood burners, which are significant sources of PM2.5 in urban areas, should be regulated more strictly. Although regulations introduced in 2022 required new burners and fuel sources to meet new standards, local authorities have been slow to enforce these regulations, with just four fines issued in 2023 – 2024. Environmental health and health protection teams should prioritise tackling air pollution, and the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government should mandate that no new-build houses in urban areas be fitted with wood-burning stoves.

The Government has recognised air pollution as the largest environmental risk to public health in the UK, directly contributing to between 28,000 and 36,000 deaths every year, at a cost to the NHS and social care of more than £40 million each year. Taking more decisive action on poor quality would help to ease pressures on health services, both directly through pressure on primary care, and in reducing one of the key underlying drivers of persistent ill-health and inequalities. Given the potent cardiotoxicity of phenanthrene, and PAHs more broadly, policymakers and public health officials should make effective steps to reduce exposure a key priority.

Cardiovascular disease threatens to leave behind lower and middle income countries

By Dr Gindo Tampubolon, Professor Delvac Oceandy, and Dr Asri Maharani

Global development has brought a welcome uplift in the quality of life for billions of people. But this transition has also introduced the new risk of cardiovascular disease through changing diets and lifestyles, placing pressures on sometimes-fragile healthcare systems. Here, Dr Gindo Tampubolon, Professor Delvac Oceandy, and Dr Asri Maharani discuss their work on health screening to identify and manage those at risk of cardiovascular disease, and how lessons from Indonesia can shape global development policy worldwide.

- Three quarters of cardiovascular deaths occur in lower- and middle-income countries.

- Mobile app-supported community screening can identify those most at risk of disease, allowing for health interventions like medication and lifestyle changes.

- Such innovations are a cost-effective way of reducing mortality and disease-burden, and can form the model for global health policy, and UK overseas development strategies.

Gains from social and economic progress over the last century have lifted billions out of extreme poverty, and reduced the scourge of infectious diseases. However, this epidemiologic transition threatens to leave behind people in lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with non-infectious and chronic diseases now coming to the fore. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death worldwide according to the World Health Organization, claiming 17.9 million adult lives each year – or one-third of global deaths. But a global figure can reveal as well as hide: three quarters of these cardiovascular deaths occur in LMICs.

The focus of research and policy should be on building and implementing cost-effective health interventions to reduce the burden of CVD in these countries. Such reduction can be achieved by helping adults manage their long-term conditions which already put a strain on the constrained healthcare system.

Sustaining health, reaping wealth with mobile technology

A project led by The University of Manchester, SMARThealth Indonesia, takes this focus by developing and implementing a mobile app-supported system that helps the Indonesian health system identify and better manage people at high risk of CVD. This work showed that 15% of high-risk patients in villages where SMARThealth was used were taking medications to manage their risk factors at follow-up, compared to just 1% receiving usual care, with the greatest difference being the use of blood pressure medication. Blood pressure was also lower in the intervention group at follow-up.

Mobile health innovation such as SMARThealth can help primary care systems identify those most at risk of CVD, and by empowering both patients and community health volunteers to make informed decisions, these innovations lower mortality from CVD. Moreover, health professionals are also helped in sharing the task of managing CVD risks in the population. In our follow up survival study of six years in Malang, the promise of the SMARThealth innovation was demonstrated by a reduced number of cardiovascular deaths in the villages, with participants in the SMARThealth trial showing an 18% lower risk of all-cause mortality.

Such effective care decisions are based on accurate information about risk factors of CVD in the villages. The most important behavioural risk factors of heart disease and stroke are unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, drinking and mostly smoking. Among environmental risk factors, air pollution is an important factor. The effects of behavioural risk factors may show up in individuals as raised blood pressure, raised blood glucose, raised blood lipids, and overweight and obesity. These intermediate risk factors can be measured in primary care posts by health volunteers and immediately indicate an increased risk of heart attack, stroke and heart failure.

Therefore, stopping smoking, reduction of salt in the diet, eating more fruit and vegetables, regular physical activity and avoiding harmful use of alcohol have been shown to reduce the risk of CVD. Interventions such as SMARThealth that create conducive environments for making healthy choices convenient and affordable are crucial for motivating people to adopt and sustain healthy behaviours. Identifying those at highest risk of CVDs, and ensuring they receive appropriate advice and treatment, can prevent premature deaths.

Healthy digital dividends worldwide

Our economic evaluation of the SMARThealth innovation demonstrates its cost-effectiveness; at a typical threshold of income per person the intervention is already 95% cost-effective, with savings per person of around US$4,000 for every year of poor health averted, and $3,600 for every CVD event averted. This resulted in it being adopted by the local government of Malang district for scale up, and it has continued to make a difference. Today more than 900,000 adults from rural Indonesia have participated in the scale up, with nearly one in five found to be at high risk of cardiovascular death in the next ten years. Ensuring that those with high CVD risk get the optimal treatment is critical and can only be achieved effectively with harnessing mobile technology in the hands of health volunteers and health professionals as demonstrated by the SMARThealth technology.

In short, the results suggest that instead of reinventing the wheel, efforts can be directed towards culturally adapting and integrating many of the technological innovations and interventions from other LMICs to strengthen health systems across the global South. In Malaysia, for instance, CVD has been the leading cause of death since the 1980s, accounting for 15% of medically certified deaths in 2019 and surpassing cancer-related deaths. Yet many adults remain unaware of their risk levels. We are engaged in efforts to share our learnings with them.

Policy recommendations

Our evidence shows that this intervention provides a cost-effective model for reducing cardiovascular deaths in LMICs. As such, it should be adopted by the WHO beyond the South-East Asia region where the SMARThealth technology has been curated into a best practice. The Western Pacific, Americas, and African regions all contain high proportions of LMICs, where an increased incidence of CVD would place a heavy burden on developing economies.

The UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) should also consider its broader adoption where it can be used to support the Commonwealth countries, the majority of which are LMICs. Health is the second biggest component of the FCDO’s Development Assistance programme, with a budget of more than £640 million. Funding programmes like SMARThealth offer a cost-effective allocation of the population health segment of this budget, helping to meet the UK’s commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals, as well as the government’s objective of modernising international development, by strengthening health systems and putting the tools and expertise in the hands of local health leaders.

Contributors

Dr Heather Agnew - Heather is a researcher in the School of Medical Sciences and Clinical Research Fellow at Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust.

Dr Saif Al-Chalabi - Saif is a researcher in the Division of Cardiovascular Sciences and Clinical Research Fellow at Salford Royal Foundation Trust.

Dr Kiera Bartlett - Kiera is a Lecturer in Psychology at The University of Manchester.

Professor Emma Crosbie - Emma is a Professor of Gynaecological Oncology at The University of Manchester.

Professor David French - David is Chair in Health Psychology at The University of Manchester.

Sophie Griffiths - Sophie is a PhD student in the Division of Psychology and Mental Health.

Professor Philip Kalra - Philip is Professor of Nephrology at The University of Manchester, and Director of Research and Innovation in the Northern Care Alliance.

Dr Sarah Kitson - Sarah is a clinical academic in the Division of Cancer Sciences.

Dr Asri Maharani - Asri is a lecturer at the Division of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work.

Dr Brian McMillan - Brian is an NIHR Advanced Fellow at the Centre for Primary Care and Health Services Research, as well as a practising GP and a Registered Health Psychologist.

Professor Delvac Oceandy - Delvac is a Professor of Molecular Cardiovascular Sciences at The University of Manchester.

Professor Holly Shiels - Holly is a Professor in the Division of Cardiovascular Sciences.

Professor Smeeta Sinha - Smeeta is National Clinical Director of Renal Medicine at NHS England and Honorary Professor at The University of Manchester.

Dr Gindo Tampubolon - Gindo is a Reader in Global Health from the Global Development Institute at The University of Manchester.

Analysis and research on cardiovascular health

Curated by Policy@Manchester

Recommendations are based on authors’ research evidence and experience in their fields. Evidence and further discussion can be obtained by correspondence with the authors; please contact policy@manchester.ac.uk in the first instance.

Read more and join the debate at blog.policy.manchester.ac.uk

@UoMPolicy #HealthyHearts

February 2025

The University of Manchester

Oxford Road

Manchester

M13 9PL

United Kingdom

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Manchester.