Inclusive Growth in Greater Manchester 2020 and beyond

Taking Stock and Looking Forward

Executive summary

The Inclusive Growth Analysis Unit (IGAU) has taken stock of the progress that has been made in Greater Manchester (GM) towards inclusive growth, in the period since 2016 when inclusive growth started to become a prominent objective for UK cities. It has reviewed developments in policy and practice, principally those of the Mayor and GM Combined Authority (GMCA), but also of local authorities, businesses and organisations in the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector. In this legacy report, IGAU ask whether what has been done is sufficient and if not, what else could be done. The report learns from case studies from around the UK and abroad.

Inclusive growth and why we need it in GM

Inclusive growth is the idea that economic prosperity should create broad-based opportunities and have benefits to all. It challenges economic models which have produced large rises in income and wealth for some, while sustaining high levels of poverty and high levels of inequality. Since the global financial crisis, sustained economic inequalities, increasing social divisions and the rise of nationalism and populism have led to calls for different models of economic and social policy which will involve more people in economic opportunity and result in prosperity that is more widely shared.

Greater Manchester needs more inclusive growth

While the Greater Manchester economy as a whole performs relatively well compared to other UK cities outside London, it underperforms the UK economy as a whole and that of other leading European city regions, such as Munich, Helsinki and Barcelona. There are significant problems with low pay and insecure employment, with around 620,000 people in relative poverty, a majority in working households. More neighbourhoods are in the top fifth of the national indices of deprivation in 2019 than in 2015. The centre of the conurbation has seen the lion’s share of job growth since before the financial crisis, although not always benefiting local residents, while outer areas like Rochdale and Tameside continue to struggle on many economic indicators. Women, minority ethnic groups and disabled people tend to fare much worse in terms of jobs and pay than men, white, and non-disabled people.

Tackling these social and spatial inequalities would enable GM to make more use of the talents of a wider range of its people. Changing economic behaviours and labour market practices would spread the benefits of economic activity more widely, raising living standards and combatting poverty and injustice.

Greater Manchester is about to enter a new policy period with a Mayoral election in 2020 kicking off a new four-year Mayoral term and a refreshed GM strategy. The report makes recommendations about what could be done in this period to consolidate and extend the work started to date, and to set out on a more ambitious path towards a fairer economy and society in the future.

Inclusive growth policy and practice has two broad spheres of activity:

- working towards economic structures and activities that are more inclusive by design, for example: fairer systems for profit-sharing and reward; more equitable employment practices; and better quality jobs.

- making sure that local people are connected to economic opportunities, physically (in terms of housing, transport and digital connectivity) and in terms of having the education, training, health and care services they need.

Within these spheres, IGAU expect to see a particular emphasis on areas or groups of people more likely to have been excluded in the past.

Progress towards inclusive growth in GM

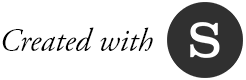

IGAU assessed progress in GM against a wide range of ideas and examples that are emerging as cities in the UK and internationally (and countries, including Scotland and Wales) experiment with policies to achieve inclusive growth. It looked at the two main spheres of inclusive growth policy – designing more inclusive economies and linking people to opportunities – and at policies to tackle social and spatial inequalities. IGAU also looked at how GM is approaching inclusive growth in terms of strategy, leadership, delivery and measurement. Table 1 summarises those findings.

Table 1. Progress on inclusive growth in GM

Table 1. Progress on inclusive growth in GM

Overall, these developments represent substantial progress. They will need to be sustained and built upon, and there will be new opportunities, such as bus franchising, which will need to be approached with an inclusive growth lens.

What has not yet happened in GM is the bringing together of these emerging policies in a clear vision and integrated approach.

Inclusive growth still means different things to different people and is more prominent in some policy areas than others. This is in contrast to some other parts of the UK where inclusive growth is being adopted as the central objective of economic plans and/or it is becoming embedded into policy-making and investment decisions through the use of inclusive growth metrics, decision tools, and new funds. Nor is inclusive growth yet a long term vision, shared by the citizens of GM, which sets out goals, values and principles about the kind of growth GM wants, how it will be achieved, and how it will serve wider social and environmental objectives and ensure a successful inclusive transition into a low-carbon, high tech future.

Full report PDF available here

Summary of recommendations

In the next Mayoral Term (2020 -2024) the Mayor of Greater Manchester should signal a commitment to inclusive growth as the central motif of his/her Mayoral term. His/her central objective should be to set GM on a long term path towards a fairer and more sustainable economy and society. To support this the political leaders of GM should adopt a clear statement of what they mean by inclusive growth and the ways in which it will make a difference to GM citizens, including those on the lowest incomes. This should be the centrepiece of the new GM strategy (GMS). Stronger mechanisms should be established to ensure that inclusive growth outcomes are considered in all major policy decisions. GM should establish a successor organisation to IGAU to ensure that it has dedicated support for research, analysis and policy development on inclusive growth. It should work with central government and other cities to make clear the principal financial, policy and regulatory barriers to inclusive growth at subnational levels and how these can be addressed in future devolution settlements.

Between 2020 and 2024, the Mayor, Combined Authority (GMCA) and other GM leaders should take specific action to embed and develop inclusive growth strategies for the economy, places and people.

On the economy they should design and build a stronger and more integrated eco-system to support the development and continuation of inclusive economy activities. Meanwhile the Mayor and GMCA should commit to the development of the good employment charter, to publishing their plan for the foundational economy, to providing support and resources to develop the work of the Co-operative Commission and to starting work on the development of mechanisms to protect quality of work and pay for workers in the ’gig’ economy. They should work with other combined authorities to review and report on opportunities and constraints in promoting good employment at city region level. The Mayor should establish an Inclusive Growth Investment Fund in order to support innovative proposals led by business, voluntary, community and social enterprise actors and to support scaling up.

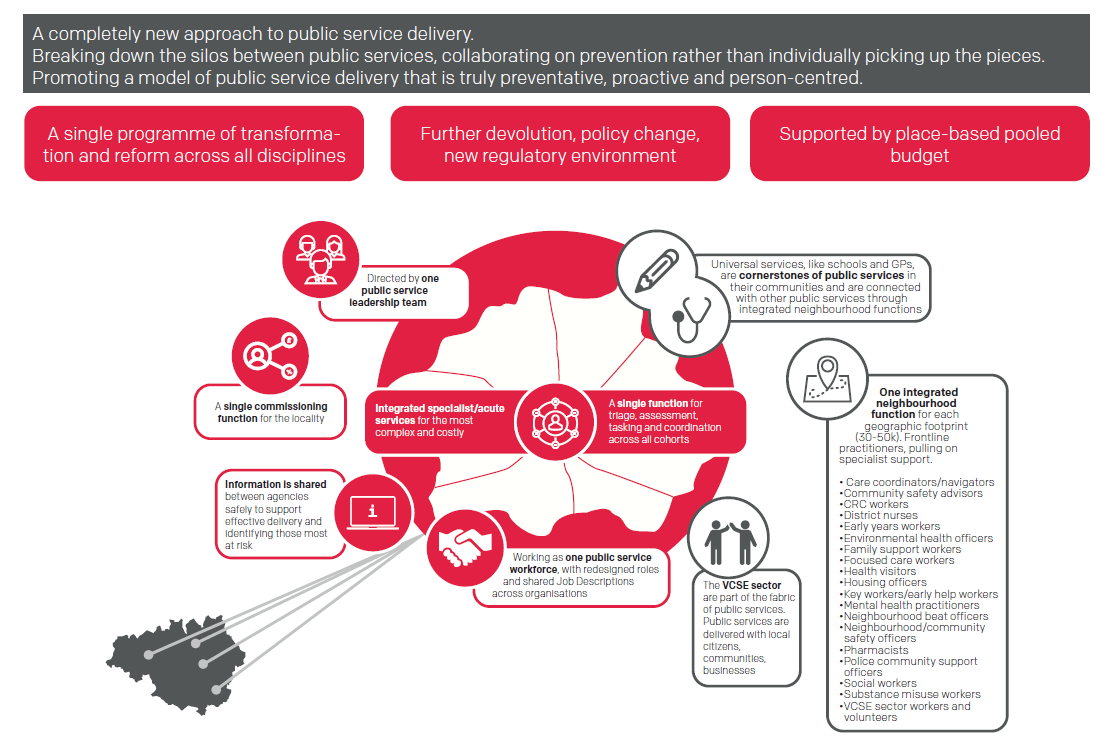

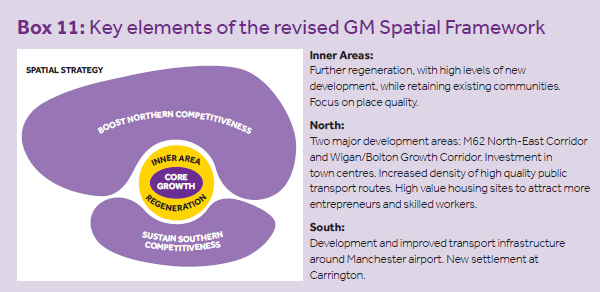

On places, GMCA should develop inclusive economy plans for all major development sites identified in the Greater Manchester Spatial Framework and for the Town Centre Challenges. The Mayor should appoint a senior figure as a Neighbourhoods Champion who should have an overall objective to make sure all neighbourhoods of Greater Manchester benefit from the city’s economic, technological, environmental and social transformation, especially those which have previously been vulnerable to the forces of change. GMCA should develop ‘Total Place Plus’ pilot projects which will build on the Unified Public Services Model to incorporate shared planning and delivery in public services with place-based social economy and employment initiatives.

On people, the Mayor and GMCA should establish strategic oversight of the GM education and training system as a whole, whether or not additional formal powers are devolved. GMCA should develop inclusive education and training plans for growth sectors, supported by the proposed GMLIS investment pot. They should strengthen links between equality and diversity strategies and education/employment/skills strategies.

The Mayor should also take steps in the next mayoral term to set a more ambitious long term economic, social and environmental vision for GM. Following the examples in the report, he/she should commission deliberative work with residents in order to understand what they mean by ‘prosperity’, ‘inclusion’, ‘living standards’ and inclusive growth and what kind of GM people want. This should be the basis for the 2024 GM strategy.

Full report PDF available here

1. Introduction

‘Inclusive growth’ – a term relatively unfamiliar in the UK five years ago but now increasingly common – captures the idea that economic prosperity should create broad-based opportunities and have benefits to all. It challenges economic models which have produced large rises in income and wealth for some, while sustaining high levels of poverty (including for those who are working) and high levels of inequality.

Definitions of inclusive growth:

‘broad-based growth that enables the widest range of people and places to both contribute to and benefit from economic success’

‘growth that combines increased prosperity with greater equity; that creates opportunities for all & distributes the dividends of increased prosperity fairly’

'growth that is distributed fairly across society and creates opportunities for all'

Over three years ago in summer 2016, IGAU's report Inclusive Growth: Opportunities and Challenges for Greater Manchester reviewed evidence of inclusive growth in GM. IGAU set out the evidence that, despite recent economic success, GM still fell a long way short of its 2020 vision to pioneer “a new model for sustainable economic growth based around a more connected, talented and greener city region where all our residents are able to contribute to and benefit from sustained prosperity and enjoy a good quality of life”. IGAU argued that, like other large ex-industrial cities, GM faced considerable challenges in achieving this vision: persistent poverty; a changing economic geography with growth concentrated in central areas; changes in labour market structure with increasing concerns about low pay, underemployment and precarious work; and large disparities in economic opportunity and outcomes between people from different social and ethnic groups. Drawing on a local consultation and emerging evidence of what inclusive growth policies might look like, we followed up with a second report: Achieving Inclusive Growth in Greater Manchester: What can be done?

A great deal has happened in GM since then: the election of a Mayor; the adoption of new Greater Manchester Strategy; publication of a revised spatial framework setting out a long-term plan for the city region; an Independent Prosperity Review (GMIPR) and a new GM local industrial strategy. Once implicit, inclusive growth has increasingly become a more explicit aim of GM strategies and policies. At the same time, wider interest in inclusive growth has grown. In the UK, a high profile RSA Commission reported in 2017; an all-party parliamentary group has continued to meet; and a new think tank (the Centre for Progressive Policy) has been established to promote the agenda. Outside the UK, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) campaign for inclusive growth in cities and its ‘champion mayors’ initiative’ has gathered pace.

As the next GM Mayoral elections approach, the aim of this report is to take stock of the progress that has been made since 2016/17 and, crucially, to consider what might be done next. Are the challenges still the same? What policies have been put in place, and are they sufficient? Is GM ‘on track’ for more inclusive growth or do efforts need to be ramped up? If more could be done, what should it be? What can be learned from the emerging national and international evidence on inclusive growth and from promising examples in other cities?

The report is structured as follows. In Chapter 2, IGAU briefly review statistical evidence on the GM economy, poverty and social and spatial inequalities. This, as IGAU sees it, is the challenge for inclusive growth. Chapter 3 explains more about what inclusive growth means and might look like in practice. IGAU also consider some other current terms and ideas related to inclusive growth and overlapping in some ways, since many of the ideas and examples it looks at could also be described in these terms – ‘economic justice’ or ‘community wealth building’ for example.

Chapters 4 to 7 review different aspects of inclusive growth policy in GM. In each, we describe and assess policy developments, in the light of emerging understandings of what inclusive growth policies might look like – drawn from a growing inclusive growth literature and knowledge base. IGAU also provide short case study examples from other places around the UK and abroad which suggest ways in which GM policies might develop. The methodology for gathering and reviewing this evidence is covered in Appendix 1. Chapter 4 covers the take up of inclusive growth ideas in GM as a whole and looks at issues of strategy, leadership, delivery and measurement. Chapters 5 and 6 cover the two principle spheres of inclusive growth activity: designing more inclusive economies and including more people in the opportunities that are created. Chapters 7 and 8 cover spatial and social inequalities and the ways in which policies are responding to these. IGAU arrive at an overall view in Chapter 9, and make a set of recommendations for taking the ‘inclusive growth agenda’ forward in GM in the next policy period.

The report will obviously be of most interest to people in GM itself. But as many city regions and other places also attempt to get to grips with inclusive growth, we hope it will be a useful reference point and guide for others in the UK and beyond.

Full report PDF available here

2. Greater Manchester in 2019:

The Challenge for Inclusive Growth

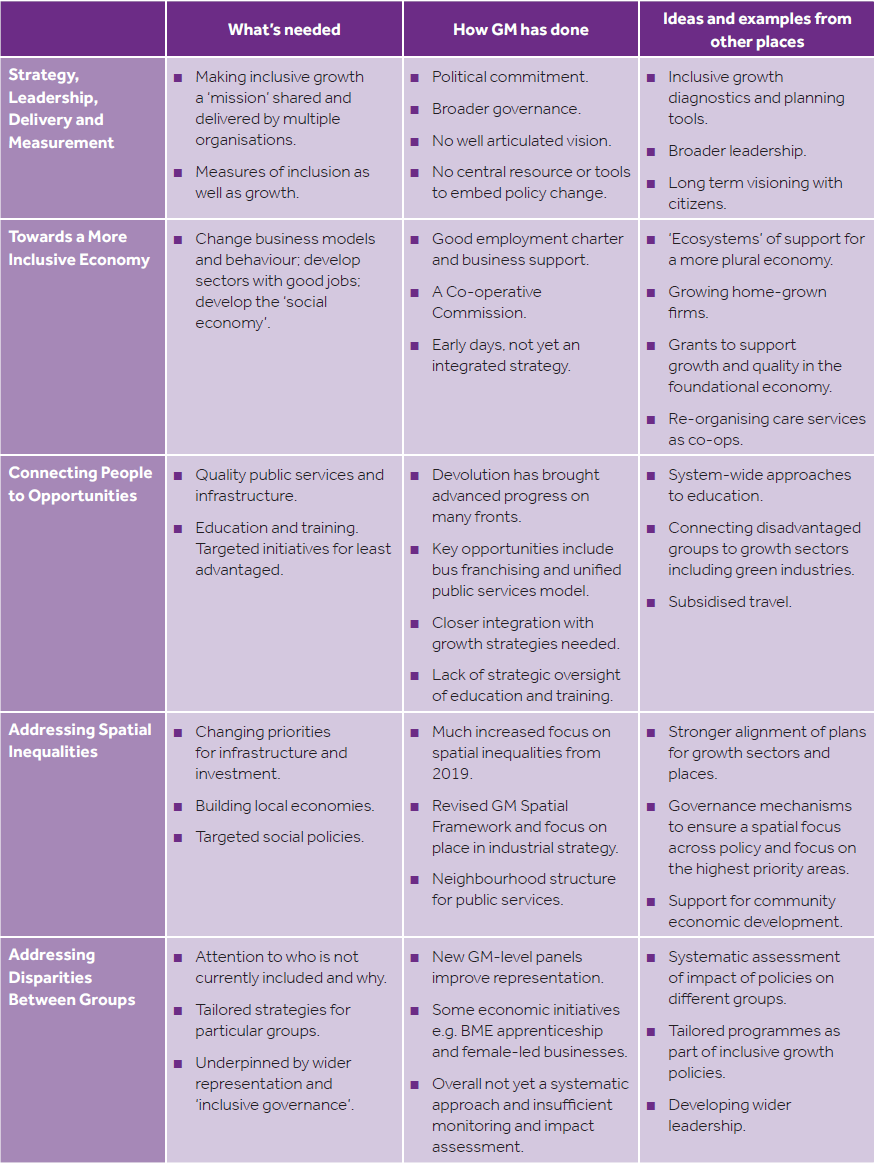

To set the scene for the report, the IGAU took a brief look at the challenges to inclusive growth in Greater Manchester, starting with an overview of the economy. As is widely recognised, the GM economy as a whole performs relatively well compared to other UK cities outside London in terms of economic growth. In 2017 (latest available figures), GM was the third largest city region economy outside London, with total GVA of £66.4 billion. This compares to £66.7bn for West of England combined authority and £69.6bn for Leeds City Region. Of the seven English core city regions outside London, GM ranked third highest in terms of GVA per filled job, with a figure of £48,1848. Figure 1 shows that, both in nominal terms and when controlling for inflation, the GM economy performed slightly better than the city region average over this period.

However, GM continues to lag behind the UK average on measures of productivity. Since 1991, it has accounted for only around 90% of the UK average on GVA per head. Just as the UK tends to underperform other comparable economies on measures of productivity, GM’s productivity is also behind that of many leading European city-regions, such as Munich, Helsinki and Barcelona, as well as Naples, Stuttgart, Cologne, and Utrecht.

Thus, on conventional measures it would appear both that GM has a relatively successful economy, within which it wants to ensure more widely shared opportunity, and that there is room to unlock further economic potential through drawing more effectively on the talents and efforts of a greater number of citizens. In the remainder of this chapter we consider some of the challenges to these ambitions.

GM’s industrial legacy

Though GM has, on the whole, successfully transitioned to a modern knowledge economy, the city region is still dealing with the legacy of its industrial past, and the rapid de-industrialisation that has followed. This transition entailed large scale job losses which had long-term economic and social consequences for individuals, their families and local communities.

One prominent manifestation of this is high levels of ill health, especially for older people. Life expectancy at birth for both male and female newborns in 2015-17 was almost two years lower in GM than for England as a whole, at 77.8 and 81.3 respectively. This figure is substantially lower in some parts of GM, with life expectancy at birth for males (2013-17) as low as 69.9 years in parts of Oldham, compared with 84.9 in parts of Stockport – a gap of 15 years. For older men, life expectancy at age 65 is 17.6 years in GM compared to 18.8 for England. GM lags behind the UK on almost all measures of public health. For example, around two-thirds of adults are overweight or obese, and one in five adults smokes. Across almost all standard published measures of alcohol harm, GM local authorities (LAs) fare significantly worse than average. In 2016, Manchester LA had the highest rate of preventable mortality in the UK, almost two and a half times higher than the area with the lowest rate. Correspondingly, more people are providing unpaid care in GM: for example, 26 people per 1000 of working age are in receipt of carers allowance compared to 21 for England overall.

Low levels of skills in the adult population also bear witness to a history of industrial employment and low employment opportunities in the post-industrial era. Around one fifth (20.6%) of working age people in GM (365,600 in total) have either no or low qualifications, compared to 18.2% for England overall, and this is higher (over 24%) in some older industrial areas Bolton, Oldham, and Rochdale. Having no or low qualifications is particularly prevalent among older working age residents (28.2% for 50-64 year olds), with a larger gap to the national figure (7.1 percentage points compared with 1.8 for 16-24 year olds). However, while educational attainment is higher among younger generations, the spatial pattern of attainment remains remarkably similar to that of earlier decades. At secondary school, the average ‘Attainment 8’ score of young people in GM was 45.4 points in 2017/18 – 1.2 points lower than England overall at 46.6 points – and lowest in Salford and Oldham (41.0 and 42.7 points, respectively). These LAs, alongside Rochdale, Tameside and Bury, have been identified as social mobility ‘coldspots’.

Changes in the economy and labour market

The figures in the previous section serve as a reminder that there is a continuing need for social investment in health, adult learning and retraining to support the development of ‘human capital’ across GM. But there are also wider changes underway in the GM economy, which are affecting the kinds of jobs that are available and the risks and rewards that workers face in different sectors. While these changes are not unique to GM they are making life more difficult in particular places and for people who are employed in less secure and poorly-paid sectors and roles.

Over recent decades, GM has broadly followed England in terms of labour market polarisation with faster growth in both professional, managerial and technical jobs, and operative and elementary jobs than ‘middle level’ and service jobs. Toward the top end of the labour market, these trends play out in rising earnings at the top and middle of the distribution – though this has come alongside rising house prices (and rental costs).

Low pay is a significant issue in GM. Median hourly pay for residents is 9% lower than the UK average, and in 2017 residents were paid over £1500 less in real terms per year than in 2008. In 2018, around 24% of employee jobs in GM were paid at or below the Living Wage (a fall since the previous year and slightly fewer than in England as a whole). Rates of underemployment have fallen since the recession, but remain higher than in 2007 at just under 6% in 2017, around one percentage point higher than in the UK (excluding GM). Job security is also an issue, with only 10% of all jobs created between 2007 and 2016 being full time positions. One in five of the GM labour force (21%) is either self-employed, employed on a temporary basis, or on a zero hours contract (ZHC), and in 2017 it was estimated that there were around 30,000 workers on ZHCs.

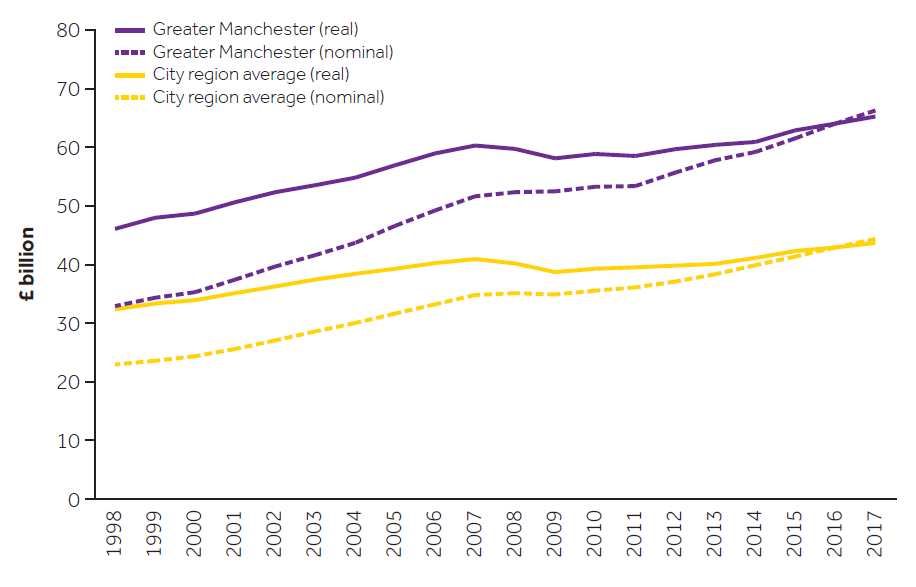

There has also been a marked spatial pattern to economic growth in GM. Nationally, economic growth based around finance, professional services and knowledge industries has largely benefited urban cores, fuelled by investment in an ‘urban renaissance’, while job growth and output growth in many former industrial towns has been sluggish. This spatial pattern is evident in GM’s growth story, with Manchester itself generating most of GM’s GVA growth since 2000 (Figure 2), due principally to growth in job numbers rather than productivity increases. Manchester also accounted for 54% of the growth in GM jobs in the period since the onset of the financial crisis. Together, Manchester, Trafford and Salford accounted for 75% of all new jobs created in GM across the ten years since 2007. In contrast, two GM LAs (Tameside and Rochdale) saw job numbers decline in this period.

The extent to which GM residents can take advantage of these patterns of job growth depends partly on skill levels and other supply-side factors including health, and also the availability and cost of transport relative to wages. GMCA’s analysis of commuting to the regional centre suggests that a large majority of workers travel in from South Manchester, Stockport and Trafford, with far fewer coming from the Northern LAs, particularly Bolton and Wigan. Competition from longer-range commuters is also an issue – 21% of workers in the regional centre commute from outside GM, with many coming from south of GM in Cheshire and High Peak, as well as Calderdale and Chorley. Manchester LA has the largest gap between weekly workplace and weekly resident wages of all core city LAs, at £63, both because workplace wages are relatively high in Manchester (third highest at £556 per week in 2018) and because resident wages are low (second lowest at £493 per week).

Spatial and social inequalities

These trends and others, not least policies of ‘austerity’, have produced a situation in which the benefits of economic growth are not currently being felt in all parts of GM and among all population groups. According to the most recent estimates, there are around 620,000 people living in relative poverty in GM, of which 61% are of working age. 3 in 5 working-age households in poverty in GM include someone who is in work. Three of GM's ten LAs (Manchester, Salford and Rochdale) are in the top decile of all LAs in Great Britain (GB) in terms of destitution rates, with Manchester being the only LA in GB in the top decile on all three types of destitution (complex needs, migrant destitution, and UK-other).

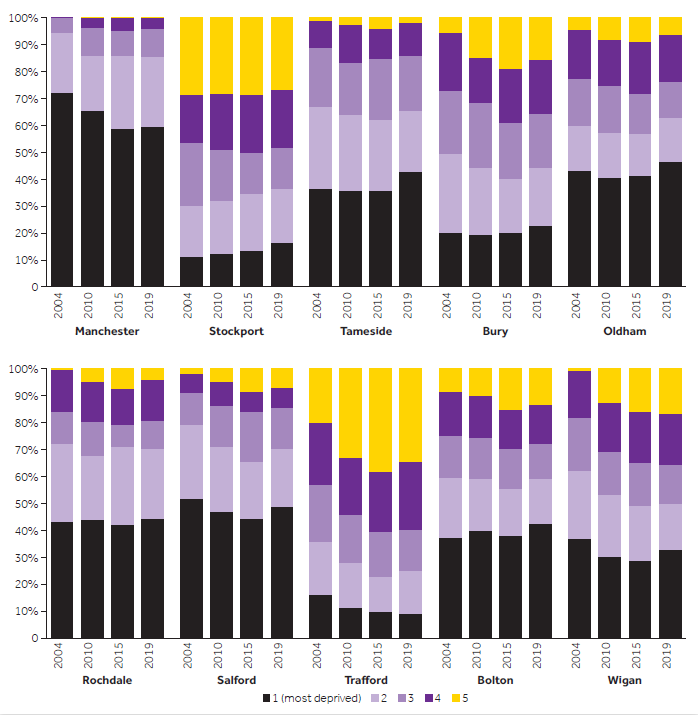

The most recent release of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) shows an increase in the proportion of GM neighbourhoods (small statistical areas known as LSOAs) among the top 10% and 20% most deprived areas in England. 23% of GM neighbourhoods were among the 10% most deprived in 2019 compared to 21% in 2015, and 38% were among the 20% most deprived in 2019 compared to 35% in 2015. This reverses a trend of improvement evident in successive releases of this data since 2004. The trends partly reveal an ‘innerouter’ issue. Manchester, Salford and Trafford are the only LAs with a smaller proportion of LSOAs in the most deprived 10% than in the IMD2004, and of the 42 extra GM LSOAs that are now in England’s most deprived decile, 26% (11 areas) are in Oldham.

IGAU’s research also shows that between 2001 and 2013, areas of severe income deprivation within the outer ring road (i.e. the M60 motorway around GM) tended to decrease in size and on rates of income deprivation, while similarly deprived areas beyond this boundary were more likely to have stayed the same or grown in size, while experiencing an increase in income deprivation rate. But this is not the whole picture. It remains the case that the majority of GM’s poorest neighbourhoods are in inner areas of North and East Manchester and Salford, in relatively close proximity to economic opportunities in the centre of GM. Many of these areas have seen reductions in deprivation rates, but in some cases this is due to more affluent people moving in rather than to decreases in the number of people in poverty. In fact, the number of people in poverty increased in the regional centre between 2001 and 2013.

Economic disparities between social groups are also large and persistent in GM. 2016 figures show that all Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups in GM were less likely to be employed than White people33. Some appear to be particularly affected by low pay. According to the GMCA, 33% of Black employees in GM are low paid, compared to 22% in Birmingham and 21% across GB.

People from BME groups are also less involved in apprenticeships. The apprenticeship ‘ethnicity gap’ for BME groups overall was 5.8 percentage points in 2015/16 meaning that whilst 16.2% of GM residents were from BME groups, they only accounted for 10.4% of all apprenticeships. They were also under-represented in higher level apprenticeships.

Employment rate gaps between disabled and non-disabled people are narrowing slightly but still large and higher in GM than for the country as a whole (in 2019,37.5 percentage points in GM compared to 33.8 in England). There also remain marked gender disparities in the labour market with men over-represented in higher-paid occupations, making up two thirds of managers, directors and senior officials while women are over-represented in roles which often attract lower pay, including caring, leisure and other service occupations. These differences manifest in the gender pay gap. While, at first glance, GM fares well on this measure, this is only because men in GM are paid poorly compared to the national average, rather than being due to women receiving relatively better pay (men in GM are 10% below the average for England, compared to 5% for women).

The future

These data indicate the scale of the challenge of inclusive growth in GM, and the need to approach it as a long term agenda not a quick policy fix. Forward projections for some of these measures indicate that some of these challenges may deepen in coming years. For example, employment forecasts suggest that Rochdale and Tameside, as well as Oldham and Wigan, are set to experience falling employment over the period to 2038; whereas jobs are forecast to grow in central and southern areas of the city region.

Since we last reported, however, it has become increasingly obvious that inclusive growth must not only be seen as a response to current inequalities and their origins in contemporary economic organisation and labour market structures, but as a way to navigate the challenges of environmental, technological and demographic change, some of which are already firmly upon us. The situation described in this chapter is in many ways the product of a failure to fairly manage the transition from an industrial to a post-industrial economy. Finding a way to achieve inclusive growth whilst addressing the challenges posed by economic and environmental change is the urgent task that national and local policy makers now face.

This challenge requires work that is well beyond the scope of the report: forecasting implications for GM; working out what action is needed, and perhaps even developing the concept of inclusive growth itself, so that it is fit for a broader purpose. Our contribution here begins to signal some of the links and future directions but much more will need to be done.

Full report PDF available here

Figure 1: Trends in Gross

Value Added (GVA), GM

compared with city region

average

. Source: ONS (2018). Regional gross

value added (balanced) by combined

authority, city regions and other

economic and enterprise regions of

the UK.

Figure 1: Trends in Gross Value Added (GVA), GM compared with city region average . Source: ONS (2018). Regional gross value added (balanced) by combined authority, city regions and other economic and enterprise regions of the UK.

Figure 2: Trends in real Gross Value Added (GVA) for GM local authorities, 1998-2017. Source: ONS (2018). Regional gross value added (balanced) local authorities (UKC North West 1998- 2017)..

Figure 2: Trends in real Gross Value Added (GVA) for GM local authorities, 1998-2017. Source: ONS (2018). Regional gross value added (balanced) local authorities (UKC North West 1998- 2017)..

Figure 3: Proportions of neighbourhoods in each quintile group of the Index of Multiple Deprivation, 2004, 2010,

2015 and 2019.

Figure 3: Proportions of neighbourhoods in each quintile group of the Index of Multiple Deprivation, 2004, 2010,

2015 and 2019.

3. Inclusive growth

Key points:

■ Inclusive growth is economic growth that creates broad-based opportunities and benefits for all.

■ Inclusive growth policy and practice includes working towards economic structures and activities that are more inclusive by design as well as making sure local people are connected to economic opportunities.

■ It often focuses on reducing spatial inequalities and improving outcomes for marginalised and disadvantaged groups. Not everyone prefers ‘inclusive growth’ as an objective. Other ideas and agendas are also concerned with building fairer economies, such as ‘economic justice’ and ‘community wealth building’. But there are often overlaps in the practical policies and strategies that are linked to these terms.

What is inclusive growth?

Inclusive growth is usually understood as economic growth that creates broad-based opportunities and benefits for all. It is presented as an alternative to models of growth which have increased the aggregate income and wealth of nations, regions or cities, but left many people and places behind.

Inclusive growth is usually understood as economic growth that creates broad-based opportunities and benefits for all. It is presented as an alternative to models of growth which have increased the aggregate income and wealth of nations, regions or cities, but left many people and places behind.

While interpretations of inclusive growth and emphases differ, the key concepts are generally agreed:

■ a concern to address inequalities, poverty and exclusion, relating to people and/or places.

■ a recognition that inclusion benefits the economy, as well as being an end in itself. Enabling more people to participate fully and fairly in economic activity is the basis for more prosperous and sustainable economies. Investment in people, services and communities should therefore be seen as an economic strategy, not a drag on the economy, and firms should expect to benefit from more inclusive employment practices.

■ a focus on the nature of the economy and labour market in producing inclusion or exclusion, not a ‘grow now, redistribute later’ model which relies on taxes, benefits and public services to correct economic inequalities. Economic activity should be organised in ways which deliver better and more widely shared social outcomes.

What inclusive growth looks like in practice

Inclusive growth policy and practice has two broad spheres of activity. One is working towards economic structures and activities that are more inclusive by design for example: fairer systems for profit sharing and reward; more equitable employment practices; better quality jobs that provide decent wages, dignity and value and opportunities to train and progress, and which support health, wellbeing and family and community life. At a local level this can include encouraging and supporting particular sectors or types of organisation, including those owned by employees, as well as influencing and supporting the behaviour of existing employers. Business finance, business support, employer pledges, and local collaborations to help employers pool functions and expertise are some of the tools that areas can draw on.

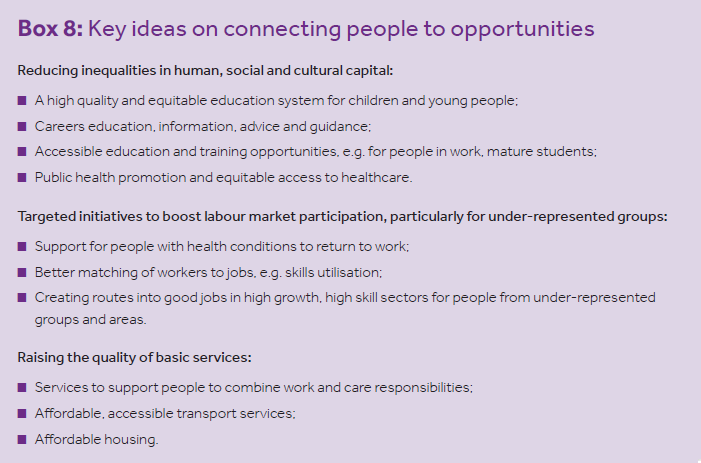

The other sphere of activity is making sure that local people are connected to economic opportunities. This involves attention to physical infrastructure – business location, affordable housing, transport connections and digital connectivity. It also involves social infrastructure such as: investment in education and training, healthcare provision and public health promotion; child and elder care; and community services.

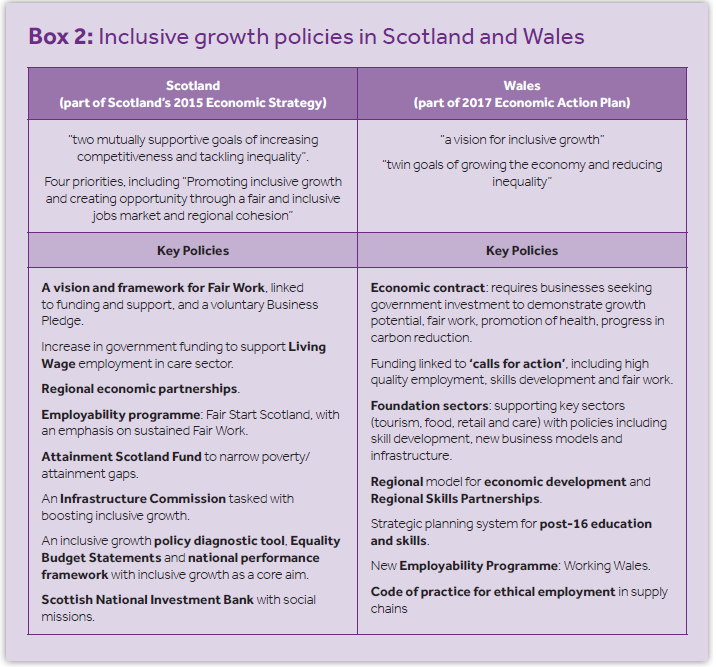

Because inclusive growth is a response to spatial and social inequalities, either or both these spheres may have a particular emphasis on areas or groups of people more likely to have been marginalised in the past. Where there is an emphasis on spatial inclusion, policy tools may include infrastructure investment, the use of planning powers, local procurement strategies, and spatial targeting of the ‘inclusive economy’ initiatives mentioned above. Where there is a concern about social inequalities, inclusive growth strategies could be expected to include stronger focus on equal opportunities in education and the labour market and specific initiatives to support under-served groups, for example minority ethnic small and medium sized enterprises. In practice the emphasis that is placed on these kinds of activity varies depending on how inclusive growth is interpreted and located within governments. In Scotland and Wales, inclusive growth is an integral objective of economic strategies. Key policies include: fair work pledges linked to business support and funding; Living Wage commitments in care sectors; employment and skills initiatives; infrastructure investments; regional economic development plans; programmes to reduce educational inequalities; improvements in childcare availability and affordability; and (in Wales) a focus on skills development, new business models and infrastructure in ‘foundational sectors’ (see Box 2). A recent report on inclusive growth in Scotland revealed high level strategic commitment and the emergence of inclusive growth as an organising principle across government but also considerable confusion about how to translate it into practice in different policy areas. There was insufficient understanding of which people and which places are currently excluded from the benefits of growth, and how policies would benefit them.

Box 2 Inclusive growth policies in Scotland and Wales. Sources: Scottish Government (2015). Scotland’s Economic Strategy; Welsh Government (2017). Prosperity for All: Economic action plan.

Box 2 Inclusive growth policies in Scotland and Wales. Sources: Scottish Government (2015). Scotland’s Economic Strategy; Welsh Government (2017). Prosperity for All: Economic action plan.

In England, policies on gender pay and pay ratio reporting, the establishment of the Race Disparity Unit and audit, the announcement in 2019 of an Office for Tackling Injustices, corporate governance reform measures, and the focus on place in industrial strategy, are consistent with the goal of ‘an economy that works for everyone’, but inclusive growth has not been adopted as economic policy. An Inclusive Economy Unit based in the Office for Civil Society in the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) focuses on the particular issue of working with businesses and investors to generate social investment and impact, rather than on more fundamental approaches to economic reorganisation such as the ownership of production, finance and taxation, and employment regulation. An All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Inclusive Growth was also established in 2014, committed to “finding a new model of inclusive growth that better benefits the majority and reconnects wealth creation with social justice”. Priorities in 2019 have included developing inclusive growth metrics and considering the impacts of automation and the future of work.

Inclusive growth is also understood differently across the English combined authorities, and this understanding is evolving over time. The North of Tyne’s devolution deal with central government had a limited definition of inclusive growth, framed in terms of employment support (including in work progression), school improvement, and adult education and skills including attraction and retention of graduates and skilled workers. In the West Midlands, which like GM was one of the pilot areas for local industrial strategies, inclusive growth is now positioned as part of an ‘inclusive, clean, and resilient economy’. Priority issues include low pay sectors, inwork progression, ethnic diversity, promoting women into sectors in which they are under-represented, youth employment, social enterprise, commissioning and procurement, vulnerability and bespoke solutions for individuals.

Thus, it is clear that while there are some broad principles and some common policy approaches encapsulated by the term ‘inclusive growth’, there is not a common understanding nor a blueprint for action. Understanding and plans are at different stages of development, and different issues are prioritised in different places.

Other ideas connected to inclusive growth

It is also important to recognise that inclusive growth is also not the only formulation of the need for a fairer economy and society that has gained (or regained) popularity in the wake of the global financial crisis. Other ideas have traction and support.

These include ‘economic justice’, ‘community wealth building’, ‘inclusive economy’, ‘shared prosperity’ and ‘social value’. Within and alongside these, there are others who emphasise the need to re-focus on the ‘foundational economy’, or who emphasise spatial rebalancing of the economy or ideas of ‘territorial justice’ (see Box 3). These ideas have different origins and are associated with different political ideologies. Some are arguably more radical in ambition than most versions of inclusive growth. Some make explicit critiques of inclusive growth: that in its emphasis on growth it is tinkering at the edges of a failed capitalist system; that its economic emphasis is too narrow to deliver social justice; that it fails to recognise the much more fundamental challenges of sustainability; that it could be seen to be dependent on growth, giving insufficient attention to economic inclusion in the existing economy; and that it is too much focused on remedying past problems than preparing for future challenges. As we show in Chapter 4, some of these ideas are underpinned by different notions of inclusion, growth, prosperity or well-being, with different measures and differently weighted priorities. But there are also some common ideas underlying these terms and much overlap in the practical policies and strategies that are implied.

The approach of the report

The main aim of this report is not to debate or contest the various terms related to inclusive growth, or indeed to defend ‘inclusive growth’ as the right term. As IGAU report, within GM, there are political differences over these terms and agendas. Some policies and practices which might be labelled as ‘inclusive growth’ in one place (such as local procurement) might be motivated in others by a commitment to ‘community wealth building’. The main objective is to document what is happening. In doing so, IGAU hopes to prompt further debate about whether inclusive growth is the right term for GM’s activities or the right ambition, and offer some helpful substance to that debate, but the ideological debate in itself is not the objective of this work.

The report is also not an evaluation of whether policies have worked. Such an evaluation should be done, but our view is that it is mostly too early to do it, partly because inclusive growth has very long term objectives (challenging decades of high inequality) and partly because it is a developing agenda. It would be unrealistic to expect that policies introduced since 2016 would have had time to make a significant difference on the ground. Even if they had, few have been evaluated in ways which make a robust assessment possible. Thus, although IGAU draw on evaluation evidence where it exists, this is not its primary ambition or approach. Instead IGAU ask three broad questions about GM’s policy direction, the extent of progress, and the possibilities for further action:

■ In what ways and to what extent do high level policy statements in GM reflect intentions towards inclusive growth?

■ What policies are actually being pursued and how do these compare with broader understandings of the suite of policies that are understood to promote inclusive growth?

■ What evidence or examples from within or beyond GM suggest promising ways in which policy might develop in the future?

IGAU divide the evidence according to the main spheres and dimensions of inclusive growth identified at the start of this chapter: developing more inclusive economies, connecting people to economic opportunities, tackling spatial inequalities, and addressing inequalities between groups. Appendix 1 describes our methodology for reaching our assessment.

Full report PDF available here

Some other key ideas linked to 'inclusive growth'

Inclusive economy: a term often preferred by critics who argue that inclusive growth is too growth-dependent or that it offers insufficient challenge to market-liberal policies that produce inequalities.

Community/local wealth building: ‘inclusive economy’ policies that focus on restructuring production and democratising ownership and control so that more economic activity has direct benefits to local residents.

Economic justice: the broad idea that economic activity should be fair – including the labour market and wage bargaining, ownership of assets and wealth, governance of firms, and financial systems.

Territorial justice: the idea (in social policy) that people should have equal access to public services wherever they live. Linked to inclusive economy ideas, may also refer to territorial ‘rebalancing’ of the economy to ensure greater spatial equality of economic opportunities and benefits.

Social value: the idea that economic actors should maximise the positive social, economic and environmental outcomes of their activity. A term increasingly used since the 2012 Social Value Act which requires public authorities to have regard to these issues.

Foundational economy: Focuses on the large portion of the economy concerned with the provision of essentials, including utilities and financial services as well as education, health and care.

Some other key ideas linked to 'inclusive growth'

Inclusive economy: a term often preferred by critics who argue that inclusive growth is too growth-dependent or that it offers insufficient challenge to market-liberal policies that produce inequalities.

Community/local wealth building: ‘inclusive economy’ policies that focus on restructuring production and democratising ownership and control so that more economic activity has direct benefits to local residents.

Economic justice: the broad idea that economic activity should be fair – including the labour market and wage bargaining, ownership of assets and wealth, governance of firms, and financial systems.

Territorial justice: the idea (in social policy) that people should have equal access to public services wherever they live. Linked to inclusive economy ideas, may also refer to territorial ‘rebalancing’ of the economy to ensure greater spatial equality of economic opportunities and benefits.

Social value: the idea that economic actors should maximise the positive social, economic and environmental outcomes of their activity. A term increasingly used since the 2012 Social Value Act which requires public authorities to have regard to these issues.

Foundational economy: Focuses on the large portion of the economy concerned with the provision of essentials, including utilities and financial services as well as education, health and care.

4. Strategy, leadership, delivery and measurement

Key points:

■ Emerging work on inclusive growth suggests that cities need to take systemic approaches, making

inclusive growth a ‘mission’ shared and delivered by multiple organisations. New metrics are needed,

measuring inclusion as well as growth.

■ There are clear political commitments to inclusive growth in GM and these have strengthened in

recent years. Approaches to governance in general have also broadened, with more people and

organisations having a say in GM strategy.

■ However, there is no clearly articulated definition of inclusive growth at the GM level and the term

means different things to different people.

■ GM has not yet established any central resource or tools to support and embed inclusive growth

across policy areas.

■ Examples from other places in the UK and abroad point to ways in which organisations can embed

inclusive growth thinking into policy development and appraisal, how they can broaden the leadership

of inclusive growth and how they can engage in longer term visioning processes involving citizens in

determining the inclusive growth outcomes they want to see.

Making inclusive growth happen

If one thing is agreed about inclusive growth, it is that it is a multi-faceted and long term agenda – not a single policy but an approach. In particular, inclusive growth brings an integration of social with economic policy spheres and so cuts across established administrative arrangements and responsibilities and requires the collaboration of multiple organisations in the private and third sectors as well as public administrations.

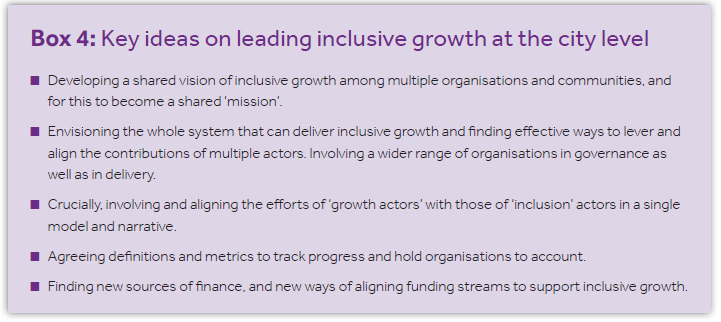

For this reason, considerable attention has been given to how cities can initiate, implement and sustain an inclusive growth approach. In the UK, this work has been led by the RSA Commission on Inclusive Growth and subsequently followed up by the RSA50 and by the Centre for Progressive Policy in a series of articles on ‘how to do inclusive growth’. Leadership strategies for inclusive growth also emerge in international research and from the OECD Champion Mayors for Inclusive Growth Initiative. Box 4 sets out some of the key ideas.

Work in this area is typically suggestive of what could be done, supported by innovative examples, rather than based on evaluation of what has ‘worked’. It is recognised that different economic, political and institutional contexts will shape how inclusive growth is led in any given place.

Box 4: Key ideas on leading inclusive growth at the city level

Box 4: Key ideas on leading inclusive growth at the city level

Inclusive growth as a strategic principle or ‘shared mission’ in GM

Inclusive growth as a principle has been recognisable in Greater Manchester and LA strategies for a long time, including in the 2013 GM strategy (GMS) which we cite in the introduction to this report. But how this vision of inclusive growth has been articulated and what it means for actual policies and practice has changed considerably in recent years.

Although it expressed the desire for everyone to contribute to and benefit from economic growth, the 2013 strategy had a clear economic/social divide. The growth strategy focused on the regional centre and other key growth sites and sectors, a market-led investment strategy and business support targeted on firms with greatest growth potential. Separately, ‘reform’ strategies (around early years, troubled families, justice, health and social care and worklessness and skills) were developed to re-design public services to build independence and self-reliance, and to reduce demand for (and cost of) public services, making GM a net contributor to the public finances.

By contrast, the GMS of 2017 was a substantially different document. Entitled ‘Our People, Our Place’ it was billed as a document for everyone in Greater Manchester, in which change would be driven “by our communities themselves… harnessing the strengths of Greater Manchester’s people and places [to] create a more inclusive and productive city region where everyone, and every place, can succeed”. “A thriving and productive economy in all parts of Greater Manchester” was only one of ten priorities covering all aspects of urban life from the early years to ageing, and the economy to the environment (Box 5).

Although the strategy did not mention inclusive growth specifically, politicians and officers often make reference to inclusive growth being “at the heart of the GMS” and the new GMS marking a move away from assumptions of social and spatial ‘trickle down’ that critics associated with previous versions of the strategy. Moreover, in launching GMIPR – an economic review designed to shape the GM local industrial strategy (GMLIS) – in May 2019, both Mayor Andy Burnham and Deputy Mayor Sir Richard Leese argued that inclusive growth was their central objective for the GMLIS. In this sense, inclusive growth could be seen as a strategic principle and a shared mission in GM. Again, however, the GMLIS document itself mentions inclusive growth only infrequently (9 times). By contrast, work towards London’s local industrial strategy (LIS) states in its first sentence (p. 2) that “the aim of London’s Local Industrial Strategy is inclusive growth – ensuring all of London’s places, people and communities can contribute to and benefit from the city’s growth, both today and in the future. As such inclusive growth also requires growth to be sustainable”.

The decision not to use the term ‘inclusive growth’ explicitly in GM leaves a situation in which it has different meanings in different articulations of GM strategy. As we describe in Chapter 7, inclusive growth is a prominent objective in the GM Spatial Framework (GMSF), referring to plans to ‘spread prosperity more widely’ by providing high quality investment opportunities across Greater Manchester. However, in the GMLIS, six of the nine mentions refer to investment in infrastructure for ‘digitally-driven, clean and inclusive growth’, while two are general aspirations and one relates to a business support programme. Nowhere in GM strategic documents is it yet set out what inclusive growth means and what policies and actions will follow from it.

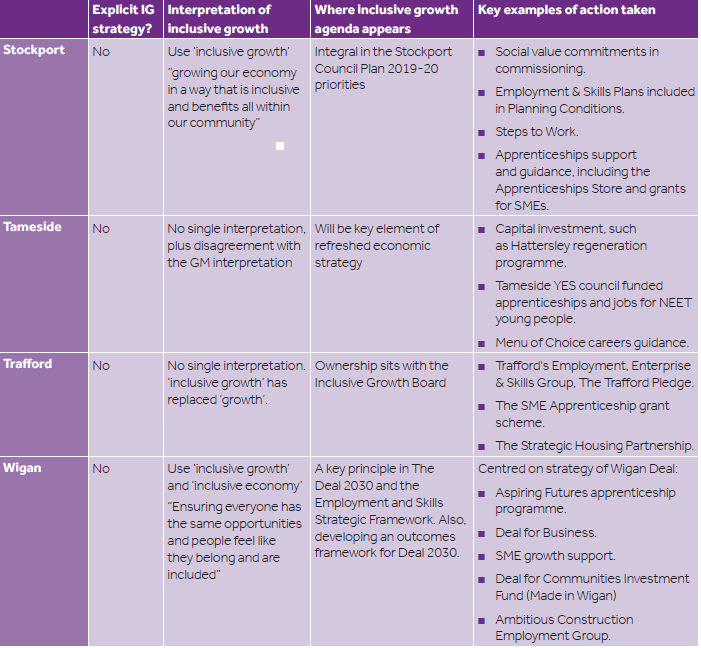

Below the GM level too, interest in inclusive growth is expressed in different ways. Our consultation with GM LAs indicates that only one (Manchester, with Salford currently developing one) has an inclusive growth strategy per se, but almost all identify inclusive growth ambitions in other strategies including economic strategies, anti-poverty strategies. work and skills strategies and overall corporate plans. There are differences in positioning and action. In Manchester, Oldham and Salford, there is an emphasis on ‘inclusive economy’. Principles of community wealth building feature strongly in Oldham. Trafford’s approach has more emphasis on growth and connecting people to opportunity. In Wigan inclusive growth has become a key element in the ‘Wigan Deal’, which is reconfiguring relationships between residents, businesses, the Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) sector and the local authority (LA) to work collectively towards a better borough.

Inclusive growth is also differently interpreted by other organisations within GM. A VCSE leadership group established in response to devolution has established an inclusive economy (not inclusive growth) sub group, while our consultation with GM housing providers indicates that although inclusive growth is a well-used term, ‘growth’ tends to relate to housing development. Thus ‘inclusive growth’ often refers to the social value that can be created through those activities as well as initiatives to support tenants to access economic opportunities (such as employment support and training).

There has been no strong lead on inclusive growth from the GM business community, except in the sense that the Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) works exceptionally closely with the Combined Authority. The GMS and GMLIS are jointly owned, and in the case of the GMLIS, jointly produced with the LEP. Business representatives have consistently reported to IGAU that ‘inclusive growth’ per se is not a term that businesses recognise or identify with, although many subscribe to the principles and practices of good employment. The GM Good Employment Charter (see Chapter 5) is bringing the Combined Authority into direct liaison with businesses over that aspect of inclusive growth. However, our various consultations with business representatives also suggest that the term can often be seen as only being about corporate social responsibility (i.e. growth should contribute to inclusion through businesses ‘giving back’) rather than as beneficial to business sustainability, productivity and growth.

Table 1: Summary of Adoption of Inclusive Growth in GM Local Authorities. Sourced from conversations with the Local Authority Inclusive Growth Network and publicly available Council documents.

Table 1: Summary of Adoption of Inclusive Growth in GM Local Authorities. Sourced from conversations with the Local Authority Inclusive Growth Network and publicly available Council documents.

A plurality of views, political objectives and different organisational usages is to be expected and should not be seen as problematic, given the principles of subsidiarity which underpin CA/LA relationships and the spirit of collaboration and co-ownership which now underpins GM policy-making. However the lack of a clear articulation of what the CA means by inclusive growth and what actions it therefore intends to take at GM level could hinder progress in a number of ways. If the term is not clearly understood, it makes it harder to align and integrate the interests of ‘growth actors’ (such as politicians and officers responsible for economic development, and business leaders) with those of ‘inclusion actors’ (politicians and officers responsible for public services, and leaders of voluntary, community and other social economy organisations). Goals to improve both growth and inclusion may co-exist but in silos. It will be harder to see why social investment or measuring impacts on poverty should be the concern of ‘growth actors’, or how economic strategies might need to be reconfigured to produce better social outcomes. Equally it will be harder to see how inclusive growth and carbon reduction strategies might be linked, or inclusive growth and digital strategies. Arguably this then weakens the power of inclusive growth as a shared mission to which other stakeholders can respond and contribute, and which they can shape. It may make it more difficult to put leadership, delivery and accountability mechanisms in place to support a long term inclusive growth agenda.

Box 5: The 10 Priorities of the Greater Manchester Strategy. Source: Greater Manchester Combined Authority

Box 5: The 10 Priorities of the Greater Manchester Strategy. Source: Greater Manchester Combined Authority

Structures, delivery and measurement

Consistent with its decision not to adopt the terminology of inclusive growth as a central mission, GMCA has not established any central unit/resource to develop its inclusive growth policies and actions ensure their embeddedness across multiple areas of policy. This approach contrasts with that of the West Midlands combined authority (WMCA), which has established an internal Inclusive Growth Unit, to ensure that inclusive growth is “hard-wired” into mainstream West Midlands investment, economic growth and local industrial strategy. The Unit provides research, analysis, insight and citizen engagement to support more inclusive policy and investment decisions, and is intended to give long term strategic support for the WMCA and its public service partners within the region. The existence in GM of the IGAU as an independent evidence resource and convenor of stakeholders may be a factor in GM’s different approach. GM has also chosen not to allocate a political portfolio holder within the Mayor’s Cabinet responsible for inclusive growth. Current portfolios most relevant to inclusive growth are those for: ‘the economy’, ‘education, skills, work and apprenticeships’; ‘community, voluntary and co-ops’; and ‘age-friendly and equalities’. However almost all other portfolios could have an element relating to inclusive growth.

Specific inclusive growth metrics, based on a re-thinking of what inclusive growth means and what measures would signal success, have also not yet been developed in GM. IGAU’s research suggests that there are many different approaches to inclusive growth measures, some more radical than others. Some simply involve measuring indicators of inclusion alongside measures of growth or prosperity. Some involve attempts to combine indicators in a single measure, so that the value of economic output is effectively weighted by the extent to which other social goals are achieved. Some keep multiple existing measures of growth and of social outcomes such as education and health, but pay much more attention to their distribution between places and population groups. Others develop frameworks which give more attention to citizens’ understanding of the meaning and value of growth and inclusion, or to the conditions and processes which underpin inclusive growth (such as resilience, participation or social and cultural infrastructure).

GM has developed an extensive outcomes framework to support the delivery of the GMS. This includes inclusive growth metrics at the level of priorities, particularly “good jobs with opportunities to progress and develop” and “a thriving and productive economy in all parts of Greater Manchester”. Elements of this framework are supported by performance dashboards, reported to the relevant body in the governance structure. This, in our view, represents advanced progress in command of data for monitoring purposes. Four things have not yet emerged or become established:

- A smaller set of high-level measures that would represent progress on inclusive growth, which might enable impact assessment tools to be developed for proposed policies or investments.

- Deliberative processes to determine priorities and trade-offs.

- A clear understanding of the relationship between measures across policy areas and the relationships between them. For instance, what measures of culture or social participation would support developments in skills, health and jobs?

- A critique of, or challenge to, existing goals or measures based on broader citizen participation and debate.

Turning to the question of wider involvement in leadership and governance, our consultation suggests that significant steps have been taken in recent years and particularly since 2017. These include the establishment of the VCSE reference group, a Mayoral accord with the VCSE sector, and various initiatives to increase voice and representation from marginalised groups (see Chapter 8). As we have documented in other work, devolution to GM has in any case (regardless of inclusive growth) fostered an increase in formal and informal partnership working and collaboration across local authority boundaries, across sectors and within and across policy boundaries. Examples include GM’s Ageing Hub, partnerships formed around the Mayor’s homelessness agenda, and the Education and Employability Board which brings together schools, colleges, universities, local authorities, DfE, Regional Schools Commissioner, GMCA, the LEP and others. High level VCSE representation has been sought for the GM Housing Commission. The University of Manchester has taken a lead with the Centre for Local Economic Strategies and GMCA in establishing a steering group to develop an ‘anchors initiative’ in GM. A number of local authorities in GM, particularly Wigan (the Wigan Deal), Manchester (Our Manchester) and Oldham (Co-operative Council/’Our Bit, Your Bit’) have sought to foster new relationships with communities, including community investments funds, asset ownership and wider involvement in decision-making. Since 2017, cross-GM conversation, partnership working and strategy formation have been mobilised on specific issues through ‘summits’ (on school readiness, social enterprise and the economy) and through formal commissions (on Cohesion and on Cooperatives). However, in respect of ‘inclusive growth’ as a whole, IGAU’s multi-stakeholder advisory board remains the key forum for discussion and representation. Our consultation also raised questions about effective representation of diverse communities, and of different parts of the VCSE sector (with voluntary, community and social enterprise elements all having very different perspectives and expertise).

Finally, we note the challenges of financing inclusive growth strategies, in the context of limited and piecemeal devolution to city-regions, a long period of austerity, and the phasing out of local government revenue support grant. Inclusive growth raises resource questions in multiple ways including but not limited to: how to finance the delivery of work at the city-region level such as good employment charters, policy development and appraisal; how to fill gaps in public funding or enhance services to meet city-region priorities (for example in relation to skills or transport); how to support innovation and evaluation; how to pool existing public and private resources in new ways; and how to increase access to finance for local business growth. Proposed solutions include establishing local financial institutions to enable local saving and lending; local investment of anchor institution assets and funds; municipal or social investment bonds; and municipal ownership or community ownership of local public assets. Devolution from central government and the capacity to pool budgets across service areas is a key issue, as will be any future settlement relating to the distribution of regional funds following the UK’s exit from the European Union (EU).

As we document throughout this report, new inclusive growth initiatives in GM are being financed in a variety of ways, including levies on taxpayers through the Mayoral precept, ‘earnback’ arrangements with central government, retained business rates, local authority and business contributions. GM Mutual, a local bank, was registered with the Financial Conduct Authority in 2019, with support from several of the GM districts, the GM Chamber of Commerce, the Federation of Small Businesses, and third sector organisations, but plans are still at early stages. As work on inclusive growth develops in GM there will be a continuing need to identify costs, benefits and financing mechanisms, including through any further devolution settlements following the government’s recently announced White Paper on devolution.

Learning from other places: see case studies 1,2,3,4

5. Towards a more inclusive economy

Key points:

■ Inclusive economy activities aim to change the way the economy functions in order to achieve a fairer distribution of economic opportunities and to deliver wider social and environmental benefits.

■ Policies that develop some of these ideas have begun to emerge in GM, including around promoting good employment practices, efforts to develop and support different types of economic activity, and recognition of the importance of the ‘foundational economy’.

■ Much of this activity is still in the early stages. GM needs to go further in embedding a commitment to build an inclusive, resilient economy with good jobs for residents.

■ Examples from other places suggest that cities can develop systemic and long-term approaches to supporting the growth of local businesses that can offer good jobs to residents. Recent examples include offering dedicated funding to support the development of inclusive economy initiatives and efforts to re-organise care services in line with co-operative principles.

Making local economies more inclusive

An inclusive economy is one where economic structures and activities are more inclusive by design, reducing inequalities and delivering wider social benefits. It rests on the idea that the economy is currently ‘exclusive’, therefore requiring intervention in key markets, sectors, business ownership models and the flow and distribution of assets and resources. The economy is re-framed as the product of collective decisions about the organisation of production and exchange – decisions which can be unmade in order to change the ways that resources are distributed, governed and owned. A better society and standard of life, good services and infrastructure and strong relations between community members are priorities, rather than economic growth in and of itself.

A key plank of local inclusive economy strategies is supporting employer behaviour that raises wages, improves job quality and builds opportunities for in-work skills development and pay progression. Approaches include employment charters, living wage policies, support for job redesign and work re-organisation in low paid sectors. Public procurement and commissioning may also be used as tools to promote better employment practices.

More broadly, cities can adopt economic strategies that, over time, support the development of activities, sectors and types of economic organisation that are more likely to deliver high quality employment for local residents as well as social and environmental benefit. These can include various forms of ‘growth from within’ approaches, rather than focusing mainly on attracting external investment, as well as strategies to stimulate employer demand for higher level skills and better use of existing skills. Places can support co-operatives and social mission focused organisations to produce core services and goods, creating a more diverse and therefore potentially more resilient economy as well as better outcomes for residents, and workers. Some make the case for treating ‘foundational’ types of activity differently, with utilities, health and social care subsidised, organised and delivered on a low risk, low return basis. Municipal ownership of assets and utilities, or co-ownership models, may also be considered.

Inclusive economy policies in Greater Manchester

From our reading of the Greater Manchester strategies, and GM-level policies, inclusive economy policies were not especially prominent in GM before 2017. However, there are some promising recent developments.

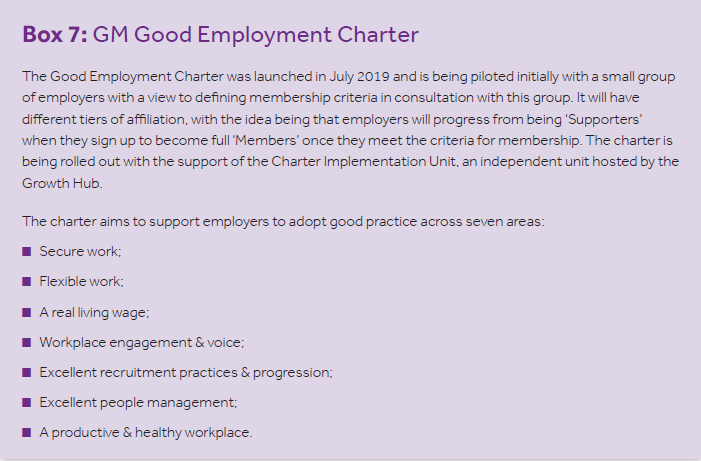

The Good Employment Charter is a particularly significant development in this area. The Charter was part of the mayor’s manifesto but has been developed through consultation with employers, unions, and employment specialists and researchers. Launched in July 2019, it is being piloted with a small group of employers who will help to set the criteria for membership. Rather than just aiming to recognise the ‘best’ employers, the charter aims to support all employers in the city region to identify how they can adopt better employment practices across seven broad themes (see Box 7). The charter has great potential but a number of challenges lie ahead.

Our review of local employment charters found that previous initiatives tended to engage a relatively small number of employers directly, in terms of accreditation and membership. However, they can play a more indirect role in initiating wider conversations and raising expectations around good employment. For GMCA, and its constituent LA members, the implementation of the charter could have a significant impact through highlighting how these organisations could improve employment practices, as well as the impact that they have in setting employment standards beyond the local authority, e.g. around commissioning of services and investment decisions. In terms of wider engagement, it is likely that significant time and resource will need to be invested to achieve the ambition of working with all employers, including those in lower paid sectors, small and micro-businesses, particularly where changing practices will have a direct impact, at least initially, on business costs. Careful integration of the charter into GM’s social value strategy and investment funds could provide strong incentives for some employers to engage with the charter.

Box 7: GM Good Employment Charter. Source: https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/what-we-do/economy/greater-manchester-good-employment-charter/

Box 7: GM Good Employment Charter. Source: https://www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/what-we-do/economy/greater-manchester-good-employment-charter/

Turning to other business-focused policies, the Growth Company (GC) is the umbrella body in GM which brings together a range of businesses and organisations supporting growth and job creation activities across the city region. In this role, it is tasked with helping to deliver against the ambitions of the GMS and has enthusiastically adopted the ‘inclusive growth’ framing within some key areas. The Growth Hub, which is part of the GC and which coordinates a range of business support services, has trained its advisors to ask those businesses who engage with their programmes a core set of ‘diagnostic’ inclusive growth questions. These questions aim to determine whether the business: pays the Living Wage; uses zero hours contracts; supports volunteering; and supports local suppliers. Business may then be referred to advisors within the Growth Hub to discuss how they might adopt these practices. However, at present the extent to which these questions lead businesses to think about how they might offer, for example, better pay, or more secure contracts is not clear. Depending on quality, the data collected by advisors could be used to track business practices, and/or the number of employers who subsequently engage with support to change these practices. This could also be helpful in planning future support services, giving an indication of the demand for more intensive support and whether this should be targeted. An Inclusive Growth steering group, which was recently set up within the Hub, could review this activity, as well as considering what other diagnostic data could be usefully connected.

The GM Business Productivity and Inclusive Growth programme, which has attracted £45 million in funding, is also being led by the Hub. The overall programme is primarily targeted at businesses with ‘the greatest potential and ability to grow and/or improve their productivity’67, including sectors with growth potential (like health innovation and advanced manufacturing) and large employment sectors (like retail and hospitality). The overall programme has the potential to support inclusive economy activities. One strand within the programme, the Large Companies Support programme, aims to help large companies to become more resilient in the face of changing markets and economic shocks through support to plan for the future. Other strands are supporting innovation and carbon reduction, with match funding from the European Regional Development Fund. Currently, the number of businesses engaged and the number of jobs created are the main targets against which progress is being reported across the different strands of activity, so it is difficult to determine the level of engagement across sectors, the types of jobs that have been created and how far this might be supporting companies to transition to a fairer, or greener approach. Outside of the Productivity and IG programme, the Hub is also working with the Chamber of Commerce to encourage small and medium-sized employers to take on apprentices.

A range of networks, organisations and policies are promoting the use of social value within GM. There is a Greater Manchester Social Value policy, currently under review, which supports information sharing, training and networking around social value across GM. As a part of the wider GMS, Greater Manchester is aiming to embed ‘quality jobs, skills provision and career progression’ as core outcomes for all skills and work contracts. For example, in 2018 the contract for the Work and Health programme was awarded to InWorkGM, a partnership between Ingeus and three social enterprises, including the Growth Company. The partnership has committed to deliver a range of social value commitments, including: ensuring that employees are paid the Living Wage; offering leadership development workshops to voluntary and community sector organisations; and ensuring that they recruit a diverse range of people, with at least 35% of people from ‘priority characteristics’ such as young (16-24) and older (over 50) people, ex-offenders, and those with a disability or health condition.

Aside from the commissioning process, parts of the Work and Health programme have also been adjusted with the aim of promoting better employment outcomes for participants. GMCA has varied the payment by outcomes model so that providers will be paid an ‘earnings fee’ if they support participants into work that pays the equivalent of the Living Wage for a specified number of hours and period, this is in contrast to the national *programme which pays providers based on the National Living Wage70. As a large share of the funding for the programme (around 45% of what was budgeted in 2018) came from EU funds it is as yet unclear what will happen when this funding expires. A more recent development which has the potential to considerably strengthen activity around the inclusive economy is the Co-operative Commission for Greater Manchester. This is an independent panel set up in 2018 to help identify ways to support the development of the co-operative sector in GM, and the role of the Combined Authority in enabling this activity. While the Commission is not due to report before this paper goes to press, initial findings indicate that GM has a relatively underdeveloped co-operative sector but that there are opportunities to strengthen support for the sector. Commission hearings have focused on housing, transport and digital sectors and ways to support the development of co-operative businesses. Alongside the Commission, a Social Enterprise Strategy is also being developed, which will set out how the sector can support the implementation of the GMLIS, whilst also promoting good jobs and innovation. The GMLIS also committed to developing a plan for the ‘foundational economy’, including looking at ways to improve productivity and job quality in these areas.

The strategy, and the GMIPR, gave significantly more attention to the importance of pay, job quality, skills and progression in the large low paid sectors which make up a large part of the GM economy than its predecessor, the Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER). However, it is as yet unclear how the foundational economy is understood in this context – whether it is being used in a more limited way as shorthand for ‘low paid sectors’, or a more expansive way including utilities and elements of ‘social infrastructure’ such as education and health. It is also as yet unclear how the plan for the foundational economy will be integrated into the wider GMLIS and the implementation plans that are being elaborated around it: failure to do so could marginalise and limit the potential of this commitment. Inclusive economy activities are also being explored and implemented by individual local authorities. Manchester has recently developed a Local Industrial Strategy, which is aligned to the GMLIS and explicitly aims to create a more inclusive economy for the people who live and work in the area. The strategy outlines plans to create quality job opportunities in the foundational economy, including working with anchor institutions. Several local authorities have committed to increase their use of social value within contracting and procurement, including adopting a 20% social value weighting when assessing tenders (e.g., Manchester, Stockport, Tameside). Many local authorities are taking steps to monitor their spending and increase the proportion that goes to local suppliers: Oldham’s community wealth building approach, for example, brings together the local authority with other local anchor institutions to increase local spend and create employment opportunities for residents. Moving beyond contracting, Salford has introduced the 10% better social value campaign, which is asking people and organisations from the third, public and private sector within Salford to make a pledge to help them to meet a variety of goals, including reducing waste, increasing recycling, increasing volunteering and increasing the number of people who are paid the Living Wage. Similar commitments also feature in the Wigan Deal, and the Deal for Business. Meanwhile, Rochdale Council is targeting some financial support, such as business rate relief, at organisations that are judged to be offering jobs with progression and development opportunities. Our consultation also suggests that housing providers are increasingly involved in building inclusive economies in their areas. There are examples from around GM of: facilitating networks of local businesses; providing enterprise advice, business skills workshops and signposting to small business grants; and grant-funding community business start-ups and consolidation, including targeting under-represented groups. Housing providers also support local social businesses through their own procurement processes. Overall, this account suggests that that there has been an emergence and strengthening of inclusive economy policies in GM in recent years. However, current initiatives are still in their early stages, rely on ad hoc funding or have been established on a short term basis, so work will be needed to put activity in this area on a more sustainable footing capable of supporting a longer term transformation of economic activity.